5.2 — Wrapping Up the Semester

ECON 315 • Economics of the Law • Spring 2021

Ryan Safner

Assistant Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/lawS21

lawS21.classes.ryansafner.com

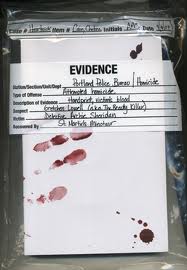

Determining Guilt or Innocence

We spent most of our focus in criminal law (and in all of our areas of law) on how law affects incentives

- i.e. deter crime; reduce accidents; encourage trade

We have not spent any time on how the legal process determines guilt or innocence

- We don’t have time to build a detailed theory

- So instead, here are two of my favorite papers on the subject

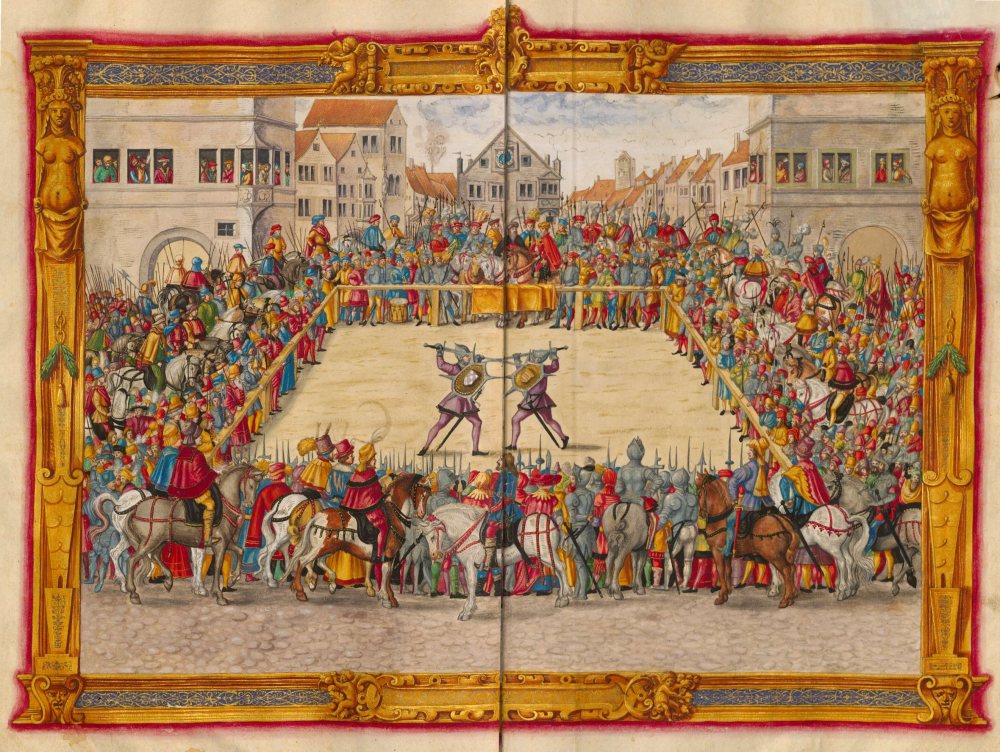

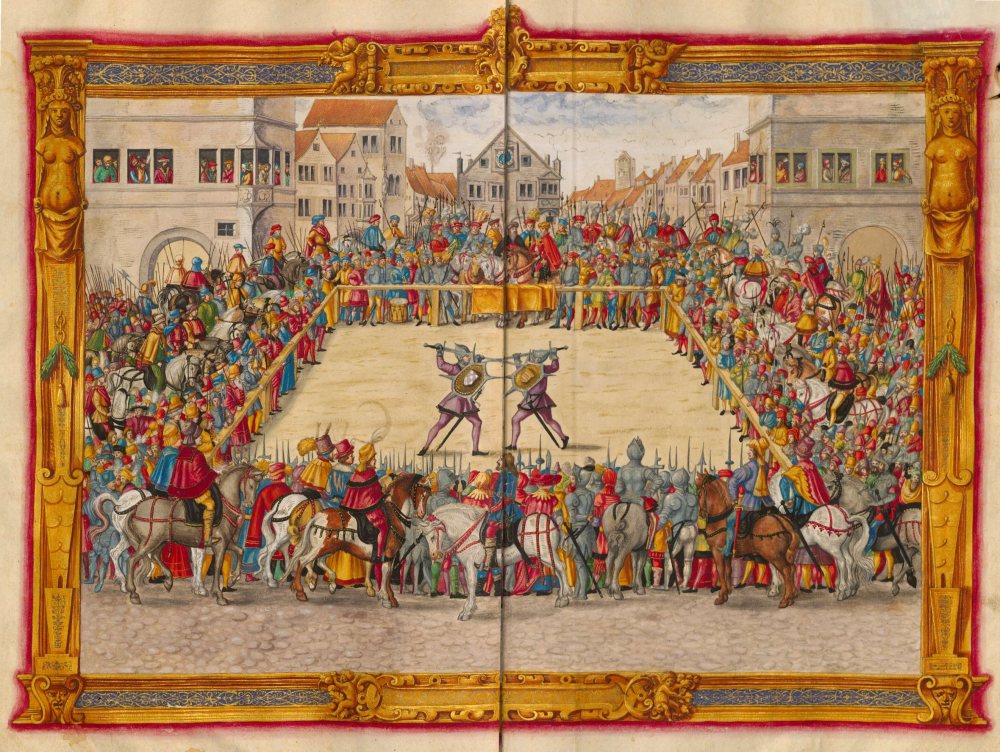

Ordeals

Obligatory

Ordeals

Peter Leeson

1979—

“For 400 years the most sophisticated persons in Europe decided difficult criminal cases by asking the defendant to thrust his arm into a cauldron of boiling water and fish out a ring. If his arm was unharmed, he was exonerated. If not, he was convicted. Alternatively, a priest dunked the defendant in a pool. Sinking proved his innocence; floating proved his guilt. People called these trials ordeals. No one alive today believes ordeals were a good way to decide defendants’ guilt. But maybe they should...Medieval judicial ordeals achieved what they sought: a way of accurately assigning guilt and innocent where traditional means couldn’t.”

Leeson, Peter T, 2012, “Ordeals,” Journal of Law and Economics 55: 691—714

Ordeals: Why They Worked

Ordeals were only used when there was uncertainty about a person's innocence or guilt

Obvious cases were settled with evidence and witnesses

Ordeals: Why They Worked

Accused is either (truly) Innocent or Guilty (with probability p)

- Choice is a message to Priest: Undergo or Refuse an ordeal

Priest observes choice, but does not know true innocence or guilt

Must find a signal such that payoffs create a separating equilibrium where (Innocent: Undergo, Guilty: refuse)

Ordeals: The Law and Economics of Superstition

Ordeals "worked" because of iudecium Dei: God would protect the truly innocent and expose the guilty during the ordeal

- Specifically, worked because of people’s believeds in iudecium Dei

Priests didn’t actually leave it in God's hands, but cleverly leveraged people's belief in iudecium Dei

Ordeals: The Law and Economics of Superstition

If people believe in iudecium Dei

and Accused ranks payoffs:

- Truly innocent: Undergo and pass

- Truly guilty: Refuse and confess

- Truly innocent: Refuse

- Truly guilty: Undergo and fail

Then:

- p(Innocent|Undergo)→1

- p(Guilty|Refuse)→1

Ordeals: The Law and Economics of Superstition

Conditional on observing the Accused’s decision to undertake ordeal, Priest knows person is (very probably) innocent

Priest rigs the Ordeal so the accused "miraculously" passes it

Events were religious, sanctimonious, ritualized, Priest had lots of (trusted) discretion

Ordeals: The Law and Economics of Superstition

Ordeals only work for people who believe in iudicium Dei

- Reserved for the most difficult cases with no evidence or witnesses

What about “skeptics”?

- Priest had to let a proportion of those undertaking ordeal fail them (even if they were innocent!)

- Maintains an equilibrium of belief in iudicium Dei

Known non-believers (or non-Christians) were not presented with Ordeals as an option

Ordeals: The Law and Economics of Superstition

In 1215, Fourth Lateran Council rejects the legitimacy of judicial ordeals, banned priests from administering them

- Belief in iudicium Dei evaporates

- Ordeals would no longer work — requires the superstition as sorting mechanism

Today we have technology that can accurately separate innocence and guilt in very hard cases (e.g. DNA evidence)

Ordeals

Peter Leeson

1979—

“Though rooted in superstition, judicial ordeals weren’t irrational. Expecting to emerge from ordeals unscathed and exonerated, innocent persons found it cheaper to undergo ordeals than to decline them. Expecting to emerge...boiled, burned, or wet and naked and condemned, guilty persons found it cheaper to decline ordeals than to undergo them. [Priests] knew that only innocent persons would want to undergo ordeals...[and] exonerated probands whenever they could. Medieval judicial ordeals achieved what they sought: they accurately assigned guilt and innocence where traditional means couldn’t.”

Leeson, Peter T, 2012, “Ordeals,” Journal of Law and Economics 55: 691—714

The Law and Economics of Superstitution: Persistance

The Law and Economics of Superstitution: Persistance

Trial By Battle

Trial By Battle

Norman conquest of England (1066) introduced trial by battle (duellum)

Until 1179, it was England’s primary judicial procedure for deciding land ownership disputes

Most dismiss it as being barbaric, irrational, ineffective solution to disputes

Trial By Battle

Peter Leeson

1979—

“This paper defends trial by battle. It examines trial by battle in England as judges used it to decide property disputes from the Norman Conquest to 1179. I argue that judicial combat was sensible and effective. In a feudal world where high transaction costs confounded the Coase theorem, trial by battle allocated disputed property rights efficiently,” (342).

Leeson, Peter T, 2011, “Trial by Battle,” Journal of Legal Analysis 3(1): 341—375

Trial By Battle: How they Worked

Demandant (Plaintiff) challenged Tenant (Defendant) via a writ of right, requesting the crown to issue an order compelling Tenant to appear before a court to defend his property

Court required evidence, such as witness testimony, to settle claims

- Also acted as screening device to reduce frivolous cases

- But, often no evidence existed, and no objective way to determine the land’s “true” owner

- Used trial by combat to determine the owner

- Again, official belief was God would favor the true owner and abandon the fraud

Trial By Battle: How they Worked

- Both parties could hire champions to serve as the combatants

- In theory, champions were supposed to be each party’s witnesses, sworn to support their claim

- In practice, parties were allowed to hire “professional” champions

- Only after 1275 did the law officially require champions be sworn witnesses

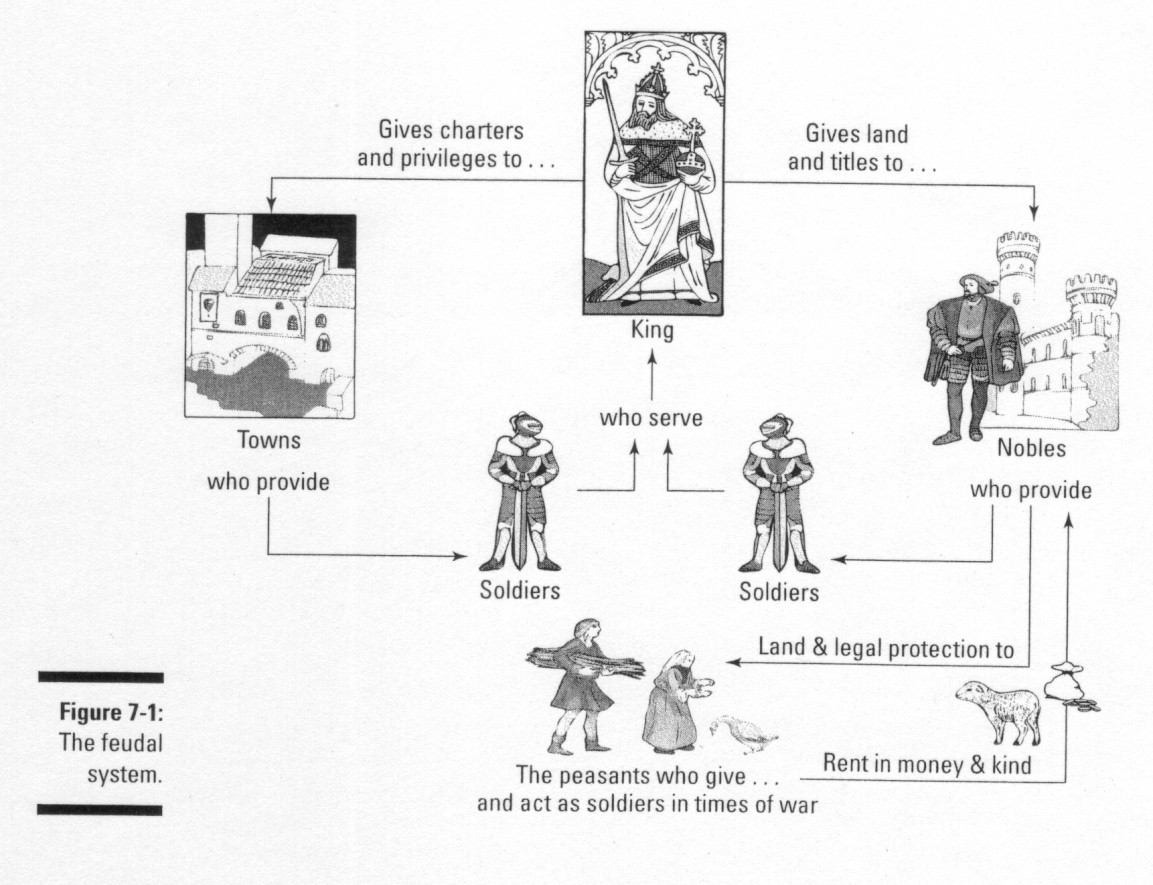

Trial By Battle: Why They Were Necessary

Feudalism: political & economic power is determined by land-ownership

All land in England is owned by the King, who rents out land to tenants

- Lords are granted their own fief to rule for the King

- Lords rent out part of their own land out to their own tenants

- All the way down to landless serfs who work their Lord’s land

Rent often in-kind or military service, only centuries later that rents paid in money

Trial By Battle: Why They Were Necessary

Under feudalism, property rights (in land) were extremely sticky

- Land is inherited by eldest son, or reallocated by authority of the crown

- All users of land (all the way down to tenants) had veto rights over changes in land use

- Not even the beginnings of a market for land until at least 13th century

Prohibitively high transaction costs for land ownership

Trials as Auctions

For efficiency, property rights should flow to their highest valued users

Coase Theorem: if transaction costs are low, this is exactly what will happen, so long as rights are clearly defined and tradeable

Ideally, we want disputes, where there is no clear evidence of legitimate ownership (for either way), to go to the party that values the land more

Trials as Auctions

Any auction tends to allocate resources to their highest valued user

- Bids generally correlate with willingness to pay

Market auction: highest bidder always wins

“Legal” auction: party spending most on attorneys increases likelihood of winning

“Violent” auction: party spending most on champion increases likelihood of winning

Trials as Auctions

All types of auction tend to allocate resources efficiently — to higher bidding party

- But auctions come with social costs

Problem 1: might be differences in endowments (wealth) that affect WTP; can mitigate with credit markets (but poor access to credit in 10th century England!)

Problem 2: bids are a transfer to the party or institution holding the auction, which creates incentives for rent-seeking

- Create bogus disputes just to extract wealth, which weakens property rights

Trials as Auctions

Peter Leeson

1979—

“Illegitimate land disputes, which result from bid recipients’ attempts to raise their incomes instead of from genuinely felt ownership disagreements, undermine property rights. They constitute socially costly rent-seeking activity rather than socially productive ownership resolution. Individuals who confront the specter of rampant rent seeking are insecure in their property rights. They live in constant fear that fraudulent legal challengers will deprive them of their property. Therefore they have weak incentives to invest in their land,” (p.342).

Leeson, Peter T, 2011, “Trial by Battle,” Journal of Legal Analysis 3(1): 341—375

Trials as Auctions

Peter Leeson

1979—

“Why didn’t Norman England’s legal system use “regular” auctions—the first-price ascending-bid variety—to auction contested property rights todisputants instead? Because regular auctions would’ve encouraged more rent seeking than violent ones. As in violent auctions, in regular ones, too, there are bid recipients...If proceeds accrue to the legal system, say to the king, or to the judges, officials have an incentive to permit and create fictitious property conflicts.

“Trial by battle’s violent auctions encouraged less rent seeking than regular auctions—and thus were less socially costly—because they generated lower bid receipts, which motivate rent-seeking behavior,” (p.342).

How Trial By Battle Reduced Social Costs

Peter Leeson

1979—

“First, unlike in a regular auction, in trial by battle’s violent auction both the higher bidder and the lower bidder must pay their bids. Expecting the higher-valuing disputant to outbid him, the lower-valuing disputant is therefore encouraged to bid less. That, in turn, allows the higher-valuing disputant to bid less too. In contrast, in a regular auction only the higher bidder pays his bid. The lower-valuing user therefore has no incentive to bid anything lower than his full valuation of the disputed right...As a result, disputants spend more to affect the allocation of disputed property rights in a regular auction than they do in trial by battle’s violent one.

How Trial By Battle Reduced Social Costs

Peter Leeson

1979—

Second, unlike in a regular auction, in trial by battle’s violent auction the higher-biddingdisputant only wins the auction probabilistically. The higher-spending disputant who sends a better champion to the arena is more likely to win the disputed right, but it’s possible for the lower-spending disputant’s inferior champion to upset him. In contrast, in a regular auction the higher-bidding disputant always wins the auction. The “randomness” in trial by battle’s violent auction, which doesn’t exist in a regular auction, reduces the value of making higher bids. That, in turn, encourages disputants to bid less. The result again is that disputants spend more to affect the allocation of disputed property rights in a regular auction than they do in trial by battle’s violent one,” (p.360).

Trial By Battle: Predictions & Evidence

Peter Leeson

1979—

“Once each disputant knows who their adversary has hired, and thus has a good idea about what he spent on the trial, battle is unnecessary. At this point both parties know the trial’s probabilistic outcome. They can save time and expense by settling their dispute instead. Thus my theory predicts that disputants should’ve settled most trials by battle. In fact it predicts that disputants should’ve always settled unless they had sufficiently different assessments of their champions’ comparative skill, or bargaining itself proved too costly and thus broke down...As long as the victorious champion’s identity isn’t a fore-gone conclusion, a mutually beneficial bargaining range that permits settlement exists. Disputants have an incentive to settle until battle is over,” (p.363).

Trial By Battle: Predictions & Evidence

Trials by battle were a mechanism meant to induce settlement between the parties, so long as it was unclear who would win

Courts took pains to minimize the social cost of the trials

- Combatants mandated to use non-lethal weapons (clubs, baculi cornuti and shields), and use protective gear; very rare a combatant was killed (only 1 documented case)

- Turned into public spectator sport; popular, well-attended (also increases the public finality of the title!)

Trial By Battle: Predictions & Evidence

Peter Leeson

1979—

“Historian of trial by battle M. J. Russell (1980a, 129) has identified 598 cases in England between 1200 and 1250 that mention trial by battle. Disputants actually wagered battle in only 226 of these cases, or 37.8 percent of the time. Champions only fought in 123 of these cases, or 20.6 percent of the time. These data suggest that disputants settled trials by battle nearly 80 percent of the time. Even taking Russell’s lower-most bound of 66.6 percent, the evidence suggests that medieval English disputants overwhelmingly settled under trial by battle. ‘[I]t is abundantly clear that trial by battle in civil cases did from an early time tend to become little more than a picturesque setting for an ultimate compromise’ (Pollock 1912: 295). ‘[B]attles were often pledged but seldom fought’ (Russell 1959, 245),” (p.364).

Trial By Battle: Predictions & Evidence

Peter Leeson

1979—

“My analysis explains how a seemingly irrational legal institution—trial by battle—is consistent with rational, maximizing behavior. It illuminates why this apparently inefficient institution played a central role in England’s legal system for so long. Most important, it demonstrates how societies can use legal arrangements to substitute for the Coase theorem where high transaction costs preclude trade,” (p.364).

Trial By Battle: Why It Ended

Peter Leeson

1979—

“When the transaction cost of trading land is low, and thus property rights in land are fluid, things are different. In this case society can rely on the Coase theorem to reallocate land to higher-valuing users if judges’ initial allocation of contested property is wrong. Trial by battle’s demand-revelation and allocation mechanism is unnecessary. It imposes a cost without a corresponding benefit. Trial by battle is inefficient. Thus my theory predicts that England’s legal system should’ve abandoned trial by battle for deciding land disputes when the transaction cost of trading land fell significantly. The history of trial by battle’s decline in English land disputes supportsthis prediction. In the second half of the twelfth century Henry II introduced important legal changes in England—the so-called Angevin reforms. These changes mark the birth of English common law and the beginning of feudalism’s end in England...In this period traditional feudal property arrangements declined significantly. With them, so did the transaction cost of trading land,” (p.366—367).

Wrapping Up the Semester

Outline and Areas of Law

- Property Law

- how do we establish who is entitled to what?

- Contract Law

- how do individuals permit use or exchange of entitlements?

- Tort Law

- how do we remedy violations of persons or entitlements?

- Criminal Law

- how does the State punish egregious harms to society?

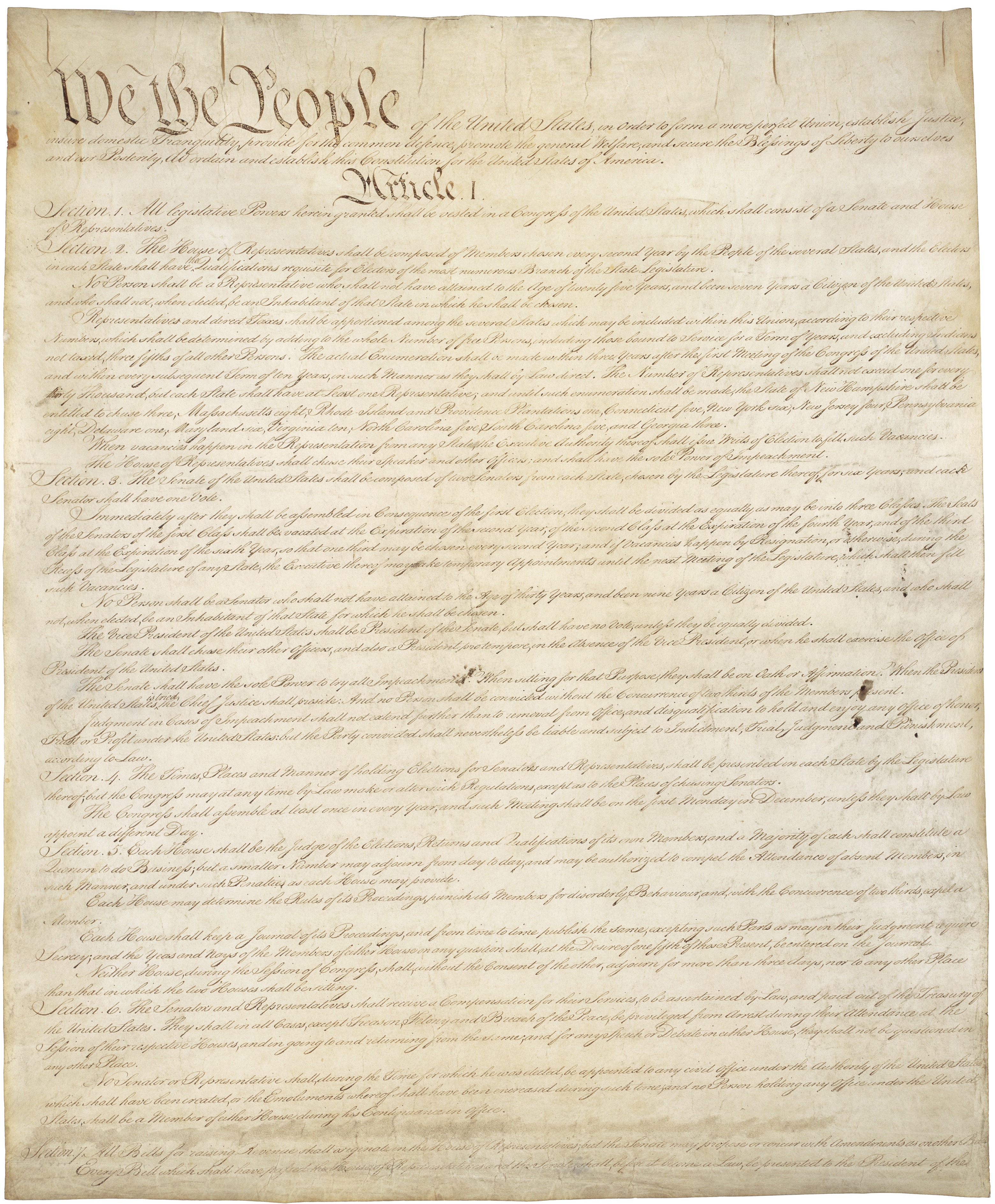

Of Course We Haven't Covered the Whole Story

Laws themselves have to come from somewhere

- Constitution, legislation, regulation, common law, custom

Political economy of how laws are determined

- Legislators, judges, police, voters are all agents that have their own objectives and respond to incentives

Three Projects in Law & Economics

Predicting consequences of law

- least controversial

Predicting what law will be

- an empirical conjecture: law is efficient

Recommending what law should be

- a normative project: law should be efficient

- You could still believe:

- law is efficient, but should not be

- law is not efficient, but should be

Recap of the Semester

We have developed theories of property/nuisance law, contract law, tort law, criminal law

Looked at how rules of legal liability create/change incentives

Thought about how these rules can be chosen to try to achieve (more) efficient outcomes

Normative Goal: Minimize Social Costs

Property law

- Goal: allocate resources/entitlements efficiently

- Or to minimize inefficiencies due to misallocation

Contract law

- Goal: further facilitate trade

- Or to decrease inefficiencies due to unrealized Kaldor-Hicks improvements

Tort law

- Goal: minimize total social costs of accidents (cost of accidents + cost of precaution)

Criminal law

- Goal: minimize total costs of crime and enforcement

Administrative Costs and Error Costs

Administrative costs

- Hiring judges, building courthouses, paying jurors, etc.

- More complex process lead to higher costs

Error costs

- Errors are judgments that differ from theoretically perfect ones

- Not about computing damages (only affects distribution, not efficiency)

- Anticipated errors affect incentives, causing inefficient precaution, activity levels, etc.

Administrative Costs and Error Costs

So theoretically, an efficient legal process (in the real world) is one that minimizes sum of:

- Direct costs of administering the system

- The economic effects of errors due to imperfect process

We've already seen tradeoff between these two types of costs:

- Simpler vs. more complex rules

Tradeoff Between Administrative & Error Costs

Whaling law: “fast fish/loose fish” vs. “iron holds the whale”

- FF/LF: lower administrative costs (fewer disputes)

- IHTW: lower error costs (better incentives for whaling)

Pierson v. Post (fox hunt case)

- Majority: first to catch, otherwise “fertile source of quarrels”

- Dissent: first to chase, hunting foxes is “meritorious”

Privatizing ownership of land

- Expanding property rights addes admin costs

- But lowers error costs (better incentives for efficient use of resource)

- Demsetz (1967): privatize when gains outweigh costs

- Same as: pick system with lower sum of admin + error costs

Goals of the Course

Not to memorize facts like which liability rules lead to efficient behavior

But to understand and learn how to think about why

This was never a law class, but a class about how to think about the law

- How people respond to incentives, the consequences of any particular rule

- Which rules would lead to efficient behavior

- And whether we should want to attain that

Big Ideas to Take Away

1) Incentives matter

(...need I say more?)

Big Ideas to Take Away

2) Efficiency as a goal is a good starting point

- Not the only goal for society, but maximizing total wealth is a good thing

- Can always redistribute resources (via government) afterwards

- Forces us to be honest about other political goals

Big Ideas to Take Away

3) Coase Theorem: can we depend on people to bargain to efficient outcomes?

- Yes, if transaction costs are low — design law to keep them low

- No, if transaction costs are high — design law to get the initial allocation correct

- Private necessity, duress, eminent domain

Big Ideas to Take Away

4) Efficiency requires incentives to engage in socially productive activities...but in excess can cause rent-seeking

- Nuisance law, contract law, tort law help people internalize externalities they cause

- Allowing people to profit from (productive, but not redistributive) information and ownership (but avoid excessive quarrels over first possession)

Big Ideas to Take Away

5) A perfect rule may not exist, even in theory...

- Paradox of compensation: single rule sets multiple parties’ incentives

- Expectation damages for contract breach can’t get both efficient breach and efficient reliance

- Tort liability can’t get efficient activity level for injurers and victims

Big Ideas to Take Away

6) ...and even if it does, it might not be what we want in practice

- Administrative costs vs. error costs

- Whaling: fast fish/loose fish vs. iron-holds-the-whale; Fox case: initial pursuer vs. final claimaint owning

- Demsetz: cost vs. benefits of property rights vs. commons

- Criminal law: deterrence is costly, but reduces crimes

Big Ideas to Take Away

7) Understand how our conclusions depend on our assumptions

- Rationality

- Perfect compensation

- Incorruptibility

- The world is a complicated place! How robust are our institutions to these real world problems?