4.5 — Criticisms & Alternatives

ECON 315 • Economics of the Law • Spring 2021

Ryan Safner

Assistant Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/lawS21

lawS21.classes.ryansafner.com

Assumptions of our Economic Model of Accidents

Our economic model of accidents has made some major assumptions:

- People are rational

- Injurers pay damages in full

- There are no regulations in place other than the liability rule

- Parties have no insurance

- Litigation is costless

- Compensation is perfect

It's gotten us some pretty neat and tidy results about efficient rules

What about in real life when none of these things are true?

Rationality

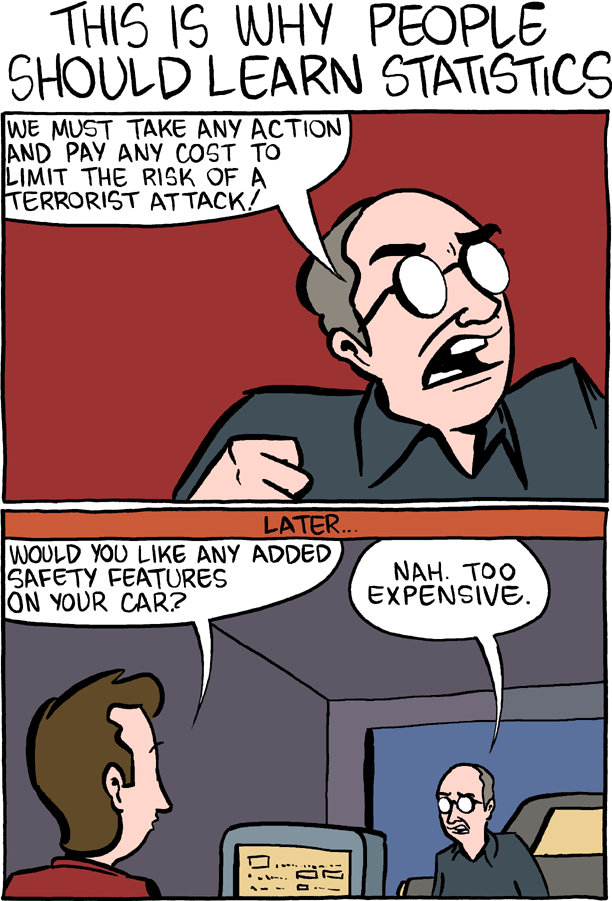

(Ir)rationality

Behavioral economics: people systematically suffer from cognitive biases

- (at least, compared to the predictions of neoclassical economic theory)

Relevant to our purposes, people are awful at estimating probability

(Ir)rationality and Probability

Hindsight bias

Recall bias & Recency bias

- People only remember the most shocking, or recent, event

- Overestimate the probability of its occurrence

Fixate on exotic, newsworthy, very low-probability events

- But forget about more commonplace hazards that are more dangerous

(Ir)rationality and Probability

- People are bad at making tradeoffs that include risk

- Or refuse to recognize that they exist

(Ir)rationality and Probability

Example: accidents with power tools

Manufacturers could design them to be safer, and consumers could use them more cautiously

Suppose consumers underestimate the risk of an accident

Negligence with defense of contributory negligence, assuming rational consumers

- Both parties take due care (x⋆,y⋆)

- leads to tools that are safe when used correctly

(Ir)rationality and Probability

But with irrational consumers who underestimate risk

- Negligence rule leads to too high number of accidents

- People assume “a product on the market must be safe” and use improperly

However, a strict liability rule is better

- Manufacturer knows consumers will probably be negligent in using product

- Design product to be extra safe (“idiot-proof”)

Rationality and Momentary Lapses

- Another aspect of this problem: unintended, momentary lapses of judgment

“[M]any accidents result from tangled feet, quavering hands, distracted eyes, slips of the tongue, wandering minds, weak wills, emotional outbursts, misjudged distances, or miscalculated consequences,” (Cooter & Ulen)

- A lot of negligence is innocently accidental

- People do try to exercise due care, but once in a while, they fail

Rationality and Momentary Lapses

A liability rule that required intentional negligence, rather than accidental negligence would be impossible to enforce

- Proving intent is even harder than proving negligence

- Most injurers would avoid liability altogether, and then take no precautions as a result!

Note there are intentional torts in common law! They overlap almost entirely with criminal offenses:

- Assault, battery, false imprisonment, conversion, trespass, intentional infliction of emotional distress, etc.

Judgment-Proof Defendants

Judgment-Proof Defendants

Assumption 2: injurers pay damages in full

Judgment-proof defendant: when Injurer’s liability is limited by bankruptcy (i.e. can’t afford to pay the full cost of damages)

Judgment-Proof Defendants

We saw strict liability causes Injurer to fully internalize expected harm done, choose efficient precaution x⋆

But what about the following example:

- Injurer causes $1,000,000 worth of harm

- Injurer only owns assets worth $100,000

- Anticipating this, he knows D<A...so he doesn’t internalize full cost of harm, takes less than efficient precaution (x<x⋆)

Judgment-Proof Defendants: Businesses

What about businesses that are judgment-proof?

Consider a hazardous waste disposal company

- One that expects to be in business for a long time has incentives to be very careful, avoid accidents/liability and harm to its reputation (and costs to shareholders)

- Vs. one that operates recklessly in the hopes of high short-term profit, pay out to shareholders, remain undercapitalized and anticipate going bankrupt after the first lawsuit

Judgment-Proof Defendants: Businesses

Example: Suppose the hazardous waste disposal company transports waste, a spill of which would create $50,000,000 of harm

Can upgrade their trucks for $225,000 to reduce likelihood of an accident from 1/100 to 1/500

- MB: Reduces expected harm from $500,000 to $100,000

- Efficient for them to do so

Judgment-Proof Defendants: Businesses

If company forced to pay $50m in damages after accident under strict liability, would choose to upgrade their trucks

But suppose the company is only worth $5,000,000

- Now, if an accident, pay $5m and go out of business

- Now the upgrade reduces expected damages from $50,000 to $10,000; not worth the cost!

Thus, judgment-proof business takes less than efficient amount of caution

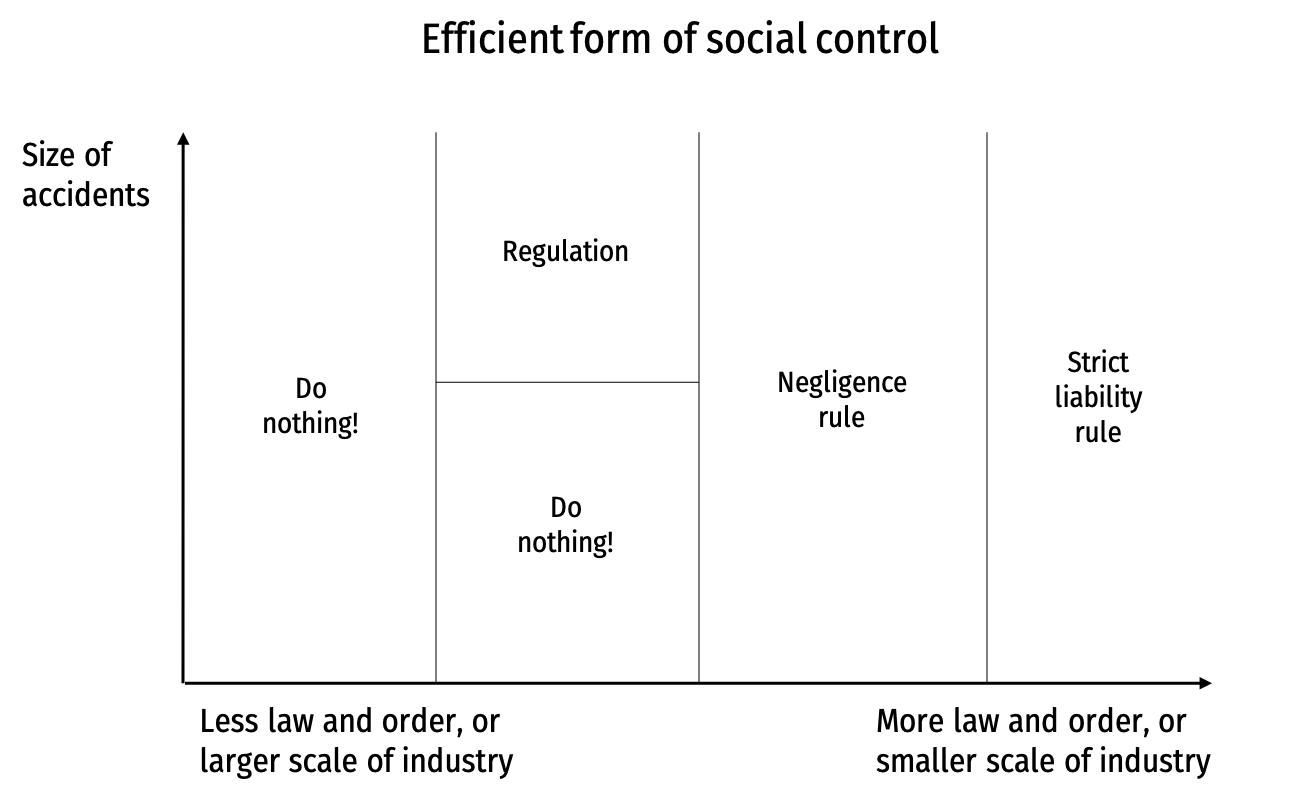

Regulation

No perfect solution to these problems

Whenever liability > injurer’s wealth, liability alone does not create sufficient incentives for efficient precaution

Regulations that mandate efficient levels of precaution can help mitigate this problem

- Inspect and assess large fines to firms that do not meet the legal standard before any accident happens

- Also works better than liability when accidents impose small harms on large group of people (nobody finds it worthwhile to sue)

Insurance

We have assumed that either Injurer or Victim bears the cost of the accident, depending on liability rule

But when either (or both) parties have liability insurance, parties don’t bear full cost of accident!

- Moral hazard problem: insured parties have weaker incentives to take precaution

- The liability rule affects the insurance companies rather than drivers or pedestrians

Insurance

- However, in real life, insurance tends to be incomplete, largely because insurance companies try to combat moral hazard:

- Deductible, coinsurance, or copayment policy; might only cover tangible harms

- Accident often causes insurance premiums to rise, so injurer not completely insulated from accident costs

- Discounts for good behavior, Drivers' Education, etc.

- Insurance company may impose safety standards required for policyholders to meet

- Can make even insured injurers face liability for their negligence!

Litigation Costs

So far, we’ve assumed litigation costs nothing

If litigation is costly (and it is!), it affects incentives in opposing directions:

If litigation is costly for Victims, they may bring fewer suits

- Some accidents go “unpunished,” leading to less incentive for Injurer precaution

If being sued is costly for Injurers, they internalize more than the cost of the accident

- Have more incentive for precaution

Litigation Costs

Under strict liability, we saw Injurers fully internalize the cost of accident, leading to them choosing efficient precaution (x⋆)

- But this assumes cost of being sued = damage done

- If courts are unpredictable, and litigation costly, private cost of being sued could > or < cost of accident

- Leading to too much or too little precaution

But if parties can’t settle out of court, and case goes to trial...

- Social cost of accident includes both the harm done and the resources spent on the trial

Litigation Costs

- Costly litigation brings about the potential of a “nuisance suit”

- Lawsuit with no legal merit, solely intended to extract an out-of-court settlement

Litigation Costs: A Kind of Nuisance Suit

Who Pays the Litigation Costs?

In U.K., the loser often pays the legal fees of the winner, “The English Rule”

- Discourages nuisance suits

- But also discourages suit where there was actual harm (but hard to prove)

In U.S., each side generally pays their own legal costs, “The American Rule”

- Some States have laws that change this under certain circumstances

Who Pays the Litigation Costs?

- Rule 68 of Federal Rules of Civil Procedure:

“At any time more than 10 days before the trial begins, a party defending against a claim may serve upon the adverse party an offer [for a settlement]... If the judgment finally obtained by the offeree is not more favorable than the offer, the offeree must pay the costs incurred after the making of the offer.”

“Fee-shifting rule”

Example: I hit you with my car, you sue me.

- Before trial, I offer to settle for $6,000, you refuse

- You win at trial, but damages are only $5,000

- Then you would have to pay all of my legal expenses after I made the offer

Who Pays the Litigation Costs?

Rule 68 encourages settlements in two ways:

- Gives Defendant added incentive to make a serious settlement offer

- Gives Plaintiff added incentive to accept the offer

A one-sided rule

- Plaintiff is penalized for rejecting Defendant's offer

- Defendant is not penalized for rejecting an offer from Plaintiff

How to Reduce Litigation Costs

If all courts cared about was efficiency:

At the start of every lawsuit, flip a coin

- Heads: lawsuit proceeds, but damages are doubled

- Tails: lawsuit immediately dismissed

Expected damages remain the same, with same incentives for precaution

- But half as many lawsuits to deal with!

(Im)perfect Compensation

(Im)perfect Compensation

Perfect compensatory damages (D=A)

- Returns victim to pre-accident level of well-being

- Works like insurance

- Sets correct incentive for Injurers

But in some cases, this is hard to determine

- Sometimes no amount of damages awarded to make victim indifferent

- Loss of a leg? Loss of a child? Life?

(Im)perfect Compensation

“Recovery for wrongful death represents damages to the survivors for the loss of value of decedent’s life. There is no special formula under the law to assess the plaintiff’s damages... It is your obligation to assess what is fair, adequate, and just. You must use your wisdom and judgment and your sense of basic justice to translate into dollars and cents the amount which will fully, fairly, and reasonably compensate the next of kin for the death of the decedent. You must be guided by your common sense and your conscience on the evidence of the case...”

- Recommended jury instructions, State of Massachusetts

“...You should award reasonable compensation for the loss of love, companionship, comfort, affection, society, solace or moral support.”

- State of California

(Im)perfect Compensation

Another odd feature of compensatory damages

Most people would rather be horribly injured than killed

- Means killing someone does more damage than injuring someone

But compensatory damages tend to be lower for a fatal accident than accident where victim is injured but not killed

- When someone is horribly injured, may require huge amount of money to compensate them

- In wrongful-death case, damages compensate a victim’s loved ones, but no attempt to compensate the victim (who is deceased)

- So damages tend to be smaller

(Im)perfect Compensation

“In China the compensation for killing a victim in a traffic accident is relatively small—amounts typically range from $30,000 to $50,000—and once payment is made, the matter is over. By contrast, paying for lifetime care for a disabled survivor can run into the millions.”

Source: Slate

What's a Life Worth?

- Assessing damages in a wrongful death suit requires some notion of what a life is “worth”

- Safety regulations also need some notion of what a life is worth

- Regulators need to decide “where to draw the line”

What's a Life Worth?

- Assessing damages in a wrongful death suit requires some notion of what a life is “worth”

- Safety regulations also need some notion of what a life is worth

- Regulators need to decide “where to draw the line”

- Kip Viscusi, 1993, “The Value of Risks to Life and Health”

- Saving an incremental life varies wildly across different types of safety regulation:

| Regulation | Estimated Cost per life saved |

|---|---|

| Airplane cabin fire protection | $200,000 |

| Car side door protection standards | $1,300,000 |

| OSHA asbestos regulations | $89,300,000 |

| EPA asbestos regulations | $104,200,000 |

| Proposed OSHA foraldehyde standard | $72,000,000,000 |

What's a Life Worth?

Most people won't answer if you ask how much money they would demand to allow you to kill them

- No amount of money that would make them indifferent between living and dying

- Conceptually: once you're dead, you have no use for the money

But, entirely possible that there is some amount of money you could give to someone to make them willing to take a probabilistic risk of dying

What's a Life Worth?

Let w be starting wealth, p be probability of death

There might exist some amount of money M such that:

pu(death)+(1−p)u(w+M)=w(w)

- Note as p→1, this breaks down

- If we can find M, we can “solve for” u(death)

- How to measure?

- Ask people how much money wthey would need to take a 1/1000 chance of death?

- Lab experiments?

- Better idea: impute how much compensation peopel require from the real life choices they make!

What's a Life Worth?

- Lots of day to day choices increase/decrease risk of death

- Choice between Volvo or sports car with fiberglass body

- Take a job washing skyscraper windows vs. office job

- But smoke detectors and fire extinguishers, or don't

What's a Life Worth?

- Reinterpret the Hand rule: precaution is cost-justified if cost of precaution < reduction in accidents × cost of accident

- Suppose side airbags reduce risk of fatal car accident by 1/1000

- If someone pays $1,000 extra for these airbags, must mean that $1,000 < 1/1000 × value of life

- or implicitly, they value their life more than $1,000,000

What's a Life Worth?

- Viscusi (1993) surveys lots of existing studies that impute value of life from people's decisions

- Wage differentials

- Decisions to speed, wear seatbelts, buy smoke detectors, smoke cigarettes

- Decisions to live in very polluted areas

- Prices of new, safer cars vs. older, more dangerous ones

What's a Life Worth?

Some findings from the paper:

| Nature of Risk, Year | Implicit Value of Life (Millions) |

|---|---|

| Highwway speed-related accident, 1973 | $0.07 |

| Automobile death risks, 1972 | $1.2 |

| Fire fatality risks without smoke detectors, 1974-1979 | $0.6 |

| Mortality effects of air pollution, 1978 | $0.8 |

| Cigarette smoking risks, 1980 | $0.7 |

| Fire fatality risks without smoke detectors, 1968-1985 | $2.0 |

| Automobile accident risks, 1986 | $4.0 |

| Improved ambulence service | $0.1 |

| Airline safety, 1975 | $15.6 |

| Job fatality risk, 1984 | $3.4-8.8 |

| Motor vehicle accidents, 1982 | $3.8 |

| Automobile accident risks, 1987, $9.7 | |

| Traffic safety | $1.2 |

What's a Life Worth?

“Although the tradeoff estimates vary considerably depending on the population exposed to the risk, the nature of the risk, individuals' income level, and similar factors, most of the reasonable estimates of the value of life are clustered in the $3 million-$7 million range...In practice, value-of-life debates seldom focus on whether the appropriate value of life should be $3 or $4 million...However, the estimates do provide guidance as to whether risk reduction efforts that cost $50,000 per life saved or $50 million per life saved are warrented. The threshold for the Office of Management and Budget to be successful in rejecting proposed risk regulations has been in excess of $100 million,” (pp.1942-1943).

What's a Life Worth?

The answer determines how much spending the government should require to prevent a single death.

The pattern of increases is scrambling a long-standing political dynamic. The business community historically has pushed for regulators to put a dollar value on life, part of a broader campaign to make agencies prove that the benefits of proposed regulations exceed the costs.

“The reality is that politics frequently trumps economics...[but] putting a price tag on life still was worthwhile, to help politicians choose among priorities and to shape the details of their proposals...Even small changes...can save billions of dollars.”

Source: New York Times, 2011

Punitive Damages

Inconsistency in Damages

Damage awards vary greatly, even for similar types of cases

We saw last week (2.3) that as long as damages are correct on average, random inconsistencies don't affect incentives

But if appropriate level of damages isn't well-established, more incentive to keep fighting for higher damages

Inconsistency in Damages

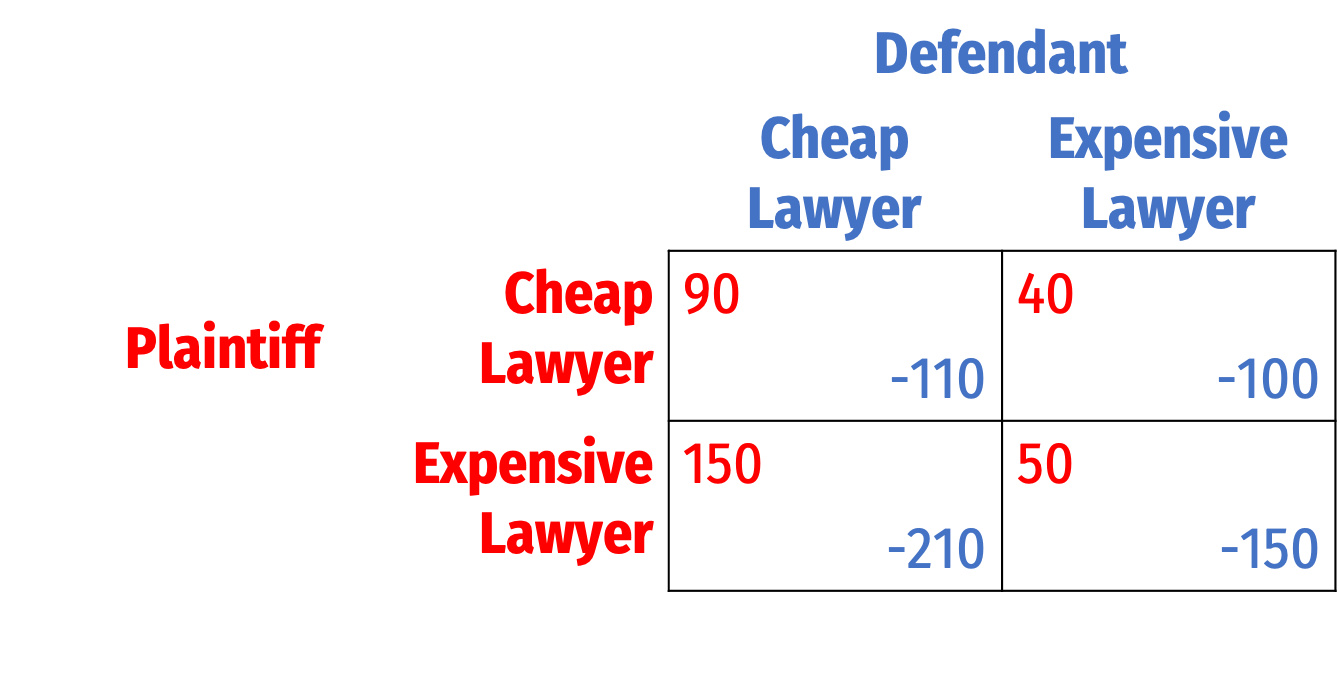

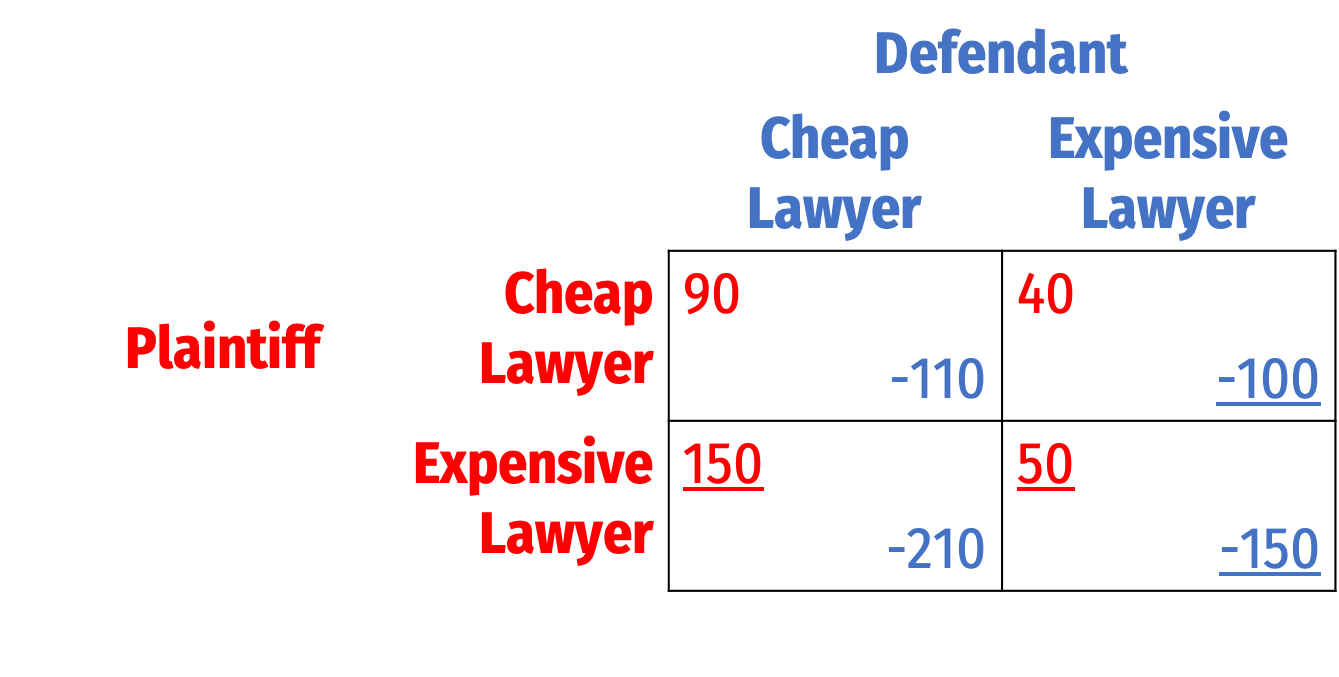

Suppose both sides can hire either a cheap lawyer or an expensive lawyer

- Cheap lawyer costs $10

- Expensive lawyer costs $50

Plaintiff will always case

With two equal lawyers, expected judgment is $100

With two different lawyers, expected judgment is doubled or halved

Punitive Damages and Incentive to Fight Hard

Nash Equilibrium: (Expensive lawyer, Expensive lawyer)

Inconsistent damages create an incentive for both parties to keep fighting and fight hard

Punitive Damages

So far (this semester), we’ve only considered compensatory damages

- Intended to make victim whole/compensate for actual harm done

Courts may additionally award punitive damages

- Meant strictly to punish the Injurer, create stronger deterrence against harm

- Not awarded for innocent mistakes, but generally when Injurer's behavior is “malicious, oppressive, gross, willful and wanton, or fraudulent”

Punitive Damages

Calculating punitive damages to award is even less well-defined than compensatory damages

Supposed to bear “reasonable relationship” to level of compensatory damages

- Unclear what this means

- U.S. Supreme Court [BMW of North America, Inc. v. Gore, (1996)] has suggested punitive damages more than ten times compensatory damages will attract “close scrutiny” (but not expressly prohibited)

- Judge Posner ruling in Mathias v. Accor Economy Lodging, Inc. (2003), 37:1 ratio is acceptable!

The McDonalds Coffee Case

Liebeck v. McDonalds (1994)

Stella Liebeck was badly burned when she spilled a cup of McDonalds coffee in her lap

She was awarded $160,000 in compensatory damages and $2,900,000 in punitive damages

This case is often the poster child for excessive punitive damages

The McDonalds Coffee Case

- Liebeck dumped coffee on her lap while trying to add cream & sugar

- Suffered third degree burns, 8 days in hospital, skin grafts, 2 years of treatments

- Initially sued for $20,000 (mostly medical costs)

- McDonalds offered to settle for $800

The McDonalds Coffee Case

- McDonalds served coffee at 180-190 degreese

- At 180 degrees, 12-15 second exposure can cause third degree burns

- Lower temperature would increase length of exposure necessary

- McDonalds had received 700 complaints of burns, had settled with some

- Quality control manager testified that 700 complaints, given how many cups of coffee McDonalds serves, was not sufficient to reexamine practices

The McDonalds Coffee Case

Rule in place was comparative negligence

- Jury found both parties negligent, McDonalds 80% responible

- Calculated compensatory damages of $200,000 × 80% ⟹ $160,000

- Added $2.9 million punitive damages

- Jury seemed to be using punitive damages to punish McDonalds for being arrogant and uncaring

Judge reduced punitive damages to 3x compensatory, so total of $640,000

During appeal, parties settled out of court for some smaller amount

The Economic Purpose of Punitive Damages

We’ve said all along, with perfect compensation, Injurer’s incentives are set correctly

So why punitive damages?

The Economic Purpose of Punitive Damages

- Example: Suppose a manufacturer can take precaution to eliminate 10 accidents a year, each causing $1,000 in damages, for a cost of $7,000

- Clearly efficient, a $10,000 reduction in expected liability for $7,000

- If every victim sued and won, manufacturer has incentive to take this precaution

- But suppose many do not, suppose only half the victims will bring successful lawsuits

- Compensatory damages total $5,000 — manufacturer is better off paying the damages instead of the (efficient) precaution

- A solution: award higher damages to the cases that are brought

The Economic Purpose of Punitive Damages

Punitive damages should be related to compensatory damages, but higher the more likely Injurer is to “get away with it”

- Example: if 50% of accidents lead to successful lawsuits, then total damages should be 2x harm, so punitive damages = compensatory damages

- if 10% of accidents lead to awards, total damages should be 10x harm, so punitive damages = 9x compensatory damages

Seems most appropriate when injurer's actions were deliberately fraudulent, may have been based on cost-benefit analysis of chance of being caught

- Better internalizes the expected cost of Injurer's actions

The Economic Purpose of Punitive Damages

Historically, punitive damages paid to victim

- Seems arbitrary, victim is already being fully compensated

- Creates much greater incentive to sue, accidents become jackpots

Some States now have laws that a share of punitive damages go to the State

- Creates own issue: State now has vested interest in seeing Plaintiffs being awarded punitive damages!

In terms of setting injurer's incentives (or punishing after the fact), doesn't really matter where money goes

- Setting it on fire would achieve same purpose (but be less efficient)

Thinking About the Legal Process Itself

Recap of the Semester

We have developed theories of property/nuisance law, contract law, and tort law

Looked at how rules of legal liability create/change incentives

Thought about how these rules can be chosen to try to achieve (more) efficient outcomes

Normative Goal: Minimize Social Costs

Property law

- Goal: allocate resources/entitlements efficiently

- Or to minimize inefficiencies due to misallocation

Contract law

- Goal: further facilitate trade

- Or to decrease inefficiencies due to unrealized Kaldor-Hicks improvements

Tort law

- Goal: minimize total social costs of accidents (cost of accidents + cost of precaution)

Hidden Assumptions

- Implicity, we’ve asssumed two things the whole time:

The legal system works flawlessly

- Whatever goal we set, we can implement correctly

The legal system costs nothing

This has allowed us to get nice theoretical results for attaining efficiency

What additional issues are there when trying to put in a legal structure to enforce our goals?

- Have to consider the legal system itself and the incentives it creates

Theory of the Second Best

We've developed a theory of the first-best outcome

- Theoretically perfect rules, implemented flawlessly, at no cost

How does reality differ? Reality is second-best

- Rules actually implemented will not be the perfect ones → imperfect incentives → less than efficient choices & outcomes

- Consider losses of efficiency due to legal imperfections as error costs

- Actual system will have administrative costs

Goal of legal system: minimize sum of these two costs

Administrative Costs and Error Costs

Administrative costs

- Hiring judges, building courthouses, paying jurors, etc.

- More complex process lead to higher costs

Error costs

- Errors are judgments that differ from theoretically perfect ones

- Not about computing damages (only affects distribution, not efficiency)

- Anticipated errors affect incentives, causing inefficient precaution, activity levels, etc.

Administrative Costs and Error Costs

So theoretically, an efficient legal process (in the real world) is one that minimizes sum of:

- Direct costs of administering the system

- The economic effects of errors due to imperfect process

We've already seen tradeoff between these two types of costs:

- Simpler vs. more complex rules

Tradeoff Between Administrative & Error Costs

Whaling law: “fast fish/loose fish” vs. “iron holds the whale”

- FF/LF: lower administrative costs (fewer disputes)

- IHTW: lower error costs (better incentives for whaling)

Pierson v. Post (fox hunt case)

- Majority: first to catch, otherwise “fertile source of quarrels”

- Dissent: first to chase, hunting foxes is “meritorious”

Privatizing ownership of land

- Expanding property rights addes admin costs

- But lowers error costs (better incentives for efficient use of resource)

- Demsetz (1967): privatize when gains outweigh costs

- Same as: pick system with lower sum of admin + error costs

How Costly Should It Be To Sue?

- Worth it for victim to sue if

expected value of legal claim

Probability of winning trial × expected damages

Or probability of settlement × expected payment

Minus costs expected to be incurred

> cost to initiate lawsuit

- “filing fees”

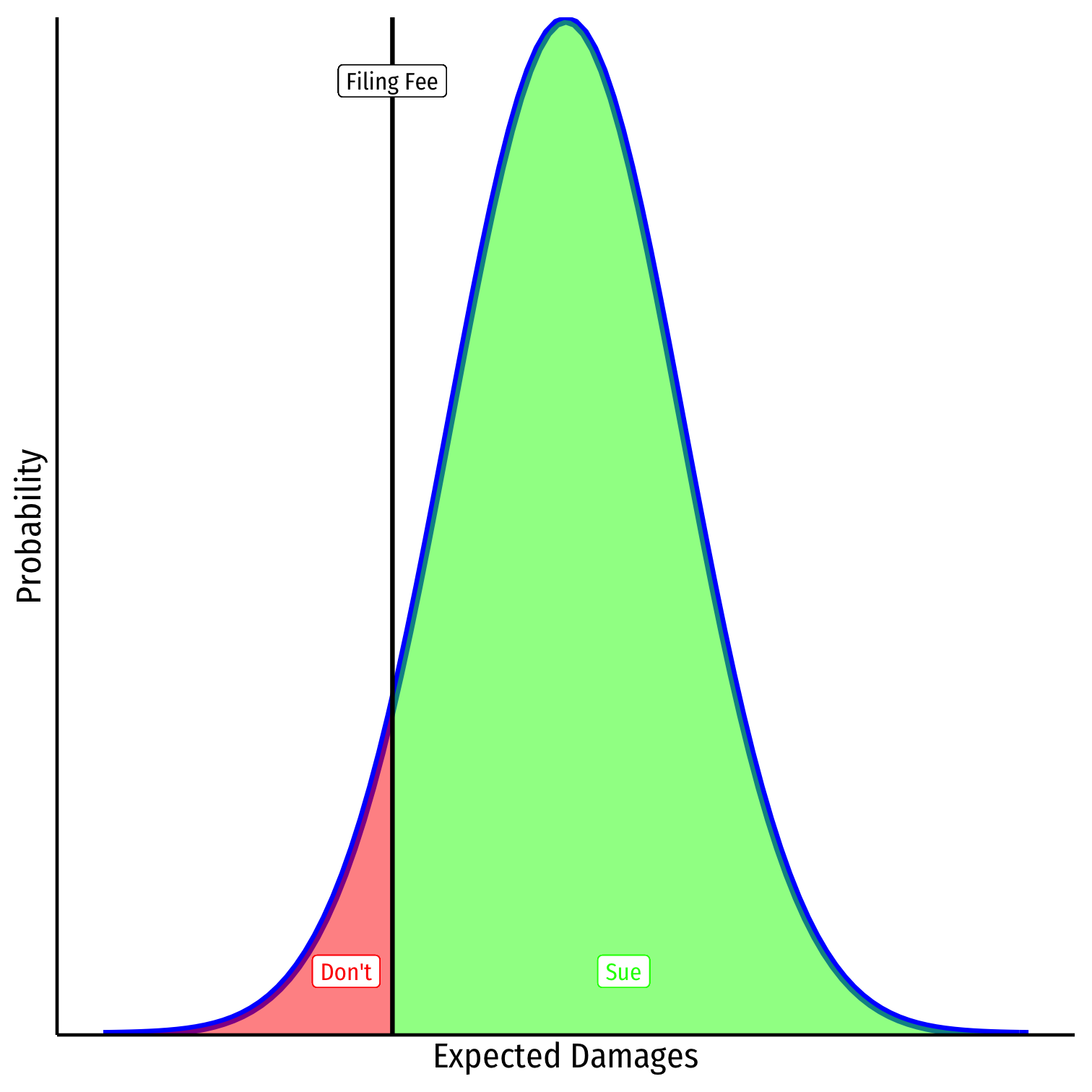

Filing Fees

Large variation in expected value of claims

Filing costs divide the distribution into those where Victim finds it worthwile to sue, and those where it isn't

Higher filing costs mean fewer lawsuits

Filing Fees

Efficient legal system minimizes sum of administrative costs and error costs

Higher filing fees → fewer lawsuits → lower admin costs

But higher fees → more injuries go “unpunished” → greater distortion in incentives → higher error costs

Filing fee is set optimally when these balance on margin:

- MC of reducing fee = MB

- Admin cost of additional lawsuit = error cost of providing no remedy in marginal case

Class Action Lawsuits

As long as litigation has any cost, some harms will be too small to justify a lawsuit

When harm is small to each individual, but large in aggregate (i.e. dispersed among many individuals), one solution is a class action lawsuit

One or more Plaintiffs brings lawsuit on behalf of large group of people harmed in similar way

- Example: California lawsuit over $6 bounced check fee

Class Action Lawsuits

Court must “certify” (approve) the class

- Participating in a class action suit eliminates victim's right to sue injurer on own

- If suit succeeds, court must then approve Plaintiff's proposal for dividing up award among members of the class

Class action lawsuits desirable when individual harms are small & aggregate harms large

- Especially when avoidance of liability has a strong effect on incentives (to injurer)

- But a danger: “class” might be so large that losing at trial would be catastrophic to Defendant, might be forced to settle even for dubious claims: “blackmail settlements”, nuisance suits

Tort Liability vs. Regulation: “The Rise of the Regulatory State”

The Rise of the Regulatory State

“Before 1900, significant commercial disputes in the United States were generally resolved through private litigation”

- This changed dramatically between 1887—1917 “Progressive Era”

“Reformers eroded the nineteenth-century belief that private litigation was the sole appropriate response to social wrongs.” “...Regulatory agencies at both the state and the federal level took over the social control of competition, anti-trust policy, railroad pricing, food and drug safety, and many other areas.”

- Why?

The Rise of the Regulatory State

“By the late nineteenth century, the development of tort law was greatly accelerated by the industrial revolution, especially the railroads.”

“Trains were also wild beasts; they roared through the countryside, killing livestock, setting fires on houses and crops, smashing wagons at gate crossings, mangling passengers and freight. Boilers exploded; trains hurtled off tracks; bridges collapsed; locomotives collided in a grinding scream of steel. Railroad law and tort law grew up, then, together.” (Lawrence Freidman)

- Very little regulation – instead, private litigation (victims bringing lawsuits)

The Rise of the Regulatory State

“Duane Lockard and Walter Murphy (1992) claim that judges supported corporations because of “a campaign to ‘educate’ judges about the sacredness of private property.”

“The thrust of the rules, taken as a whole, approached the position that corporate enterprise should be flatly immune from actions for personal injury” (Friedman)

“In addition to influencing the selection of judges and prosecutors, nineteenth-century corporations projected substantial political influence, superior lawyers, and ready access to large legal war chests. Their lawyers produced briefs that exonerated their clients and slowed down the wheels of justice for years.”

Also corruption: “intimidation and bribery of witnesses, payments and political pressures on judges and legislators, and theft and destruction of evidence…”

Political Pressure to Do Something

Many States and Federal government started passing regulatory laws that created regulatory agencies

- Pure Food and Drug Act (1906)

- Federal Reserve Act (1913)

- Federal Trade Commission Act (1916)

Over time, negligence (hard to prove) replaced with strict liability combined with regulation

Corruptibility of Institutions

So far, we’ve assumed our institutions are not corruptible

Injurer who is legally liable will be found liable in court and ordered to pay damages

Legislatures (elected by voters) and judges try to shape law towards efficient outcomes

But what if that is wrong...

Regulatory Capture

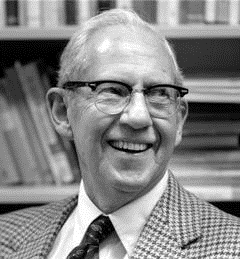

George Stigler

1911-1991

Economics Nobel 1982

“[A]s a rule, regulation is acquired by the industry and is designed and operated primarily for its benefits,” (p.3).

“[E]very industry or occupation that has enough political power to utilize the state will seek to control entry. In addition, the regulatory policy will often be so fashioned as to retard the rate of growth of new firms,” (p.5).

Stigler, George J, (1971), “The Theory of Economic Regulation,” Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science 3:3-21

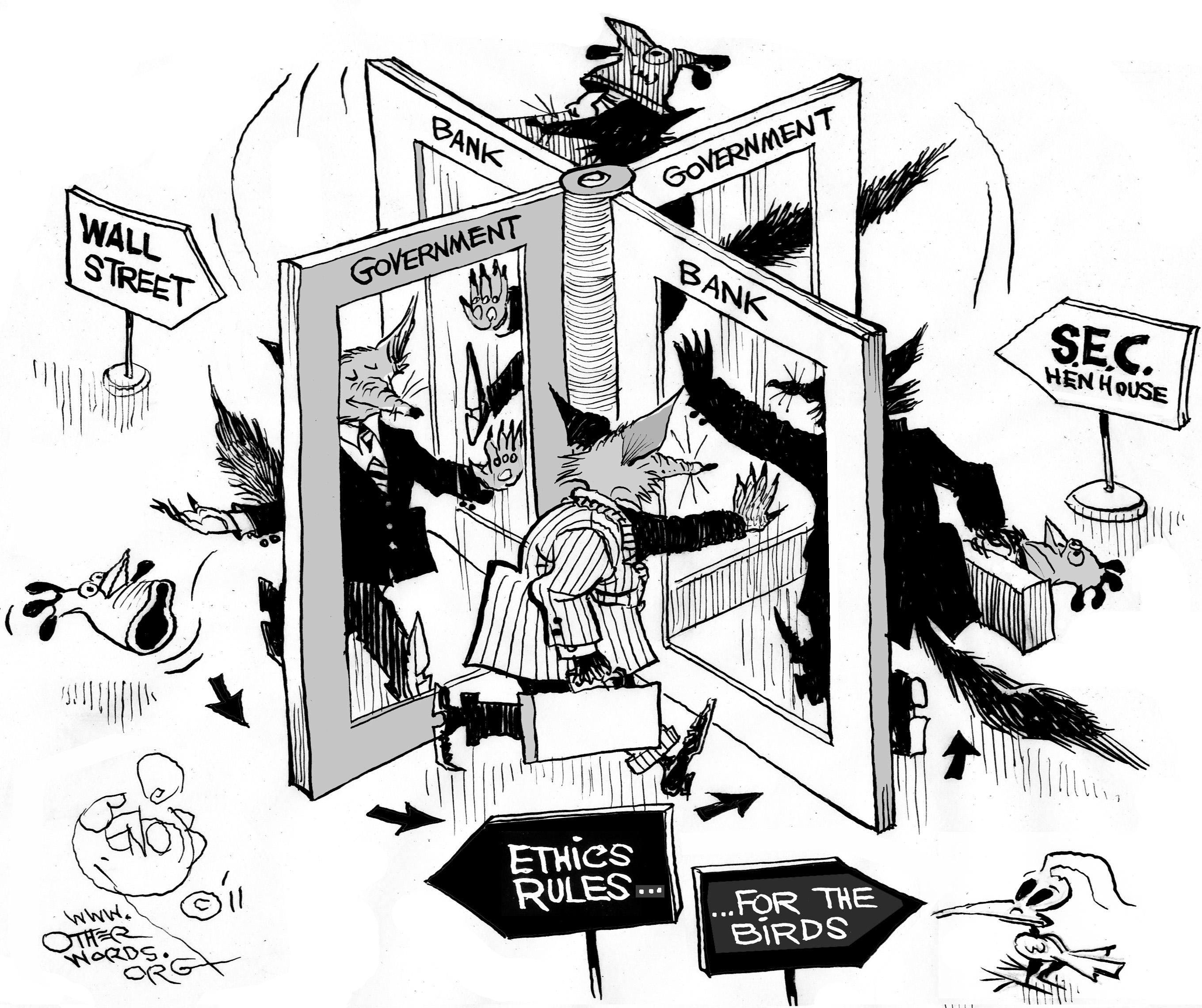

Regulatory Capture

Regulatory capture: a regulatory body is “captured” by the very industry it is tasked with regulating

Industry members use agency to further their own interests

- Incentives for firms to design regulations to harm competitors

- Legislation & regulations written by lobbyists & industry-insiders

Regulatory Capture

One major source of capture is the “revolving door” between the public and private sector

Legislators & regulators retire from politics to become highly paid consultants and lobbyists for the industry they had previously “regulated”

Not to Mention: Political Incentives

Voters, politicians, regulators, and judges are their own self-interested agents

Their objective function is not “maximize efficiency”!

Aside: Helland and Tabarrok on Electoral Institutions

- In many U.S. States, state judges campaign for office and are elected

“Politicians are not neutral maximizers of the public good; they respond to incentives, just like other individuals. A clear understanding of political behavior requires, therefore, an understanding of incentive structures. Yet with few exceptions this insight has not been applied to those politicians. we call judges. The lack of attention is surprising, since judicial incentive structures differ widely in the United States and thus provide an ideal testing ground for economic theories of politics. One important division occurs across the states. State court judges are elected in 23 states and are appointed in 27. Of the 23 elected states, ten use highly competitive parti- san elections, whereas in the remainder judges run on nonpartisan ballots. A second division occurs between federal and state judges. Federal judges are appointed and have life tenure, whereas, as just noted, many state court judges are elected and, with the exception of superior court judges in Rhode Island, none have life tenure. We argue that in cases involving corporate defendants with out-of-state headquarters, elected judges, particularly partisan elected judges, have an incentive to grant larger awards than other judges.” (pp.341-342)

Elected Judges

Aside: Helland and Tabarrok on Electoral Institutions

“Partisan elected judges must cater to their constituents, and they must raise campaign funds in order to be elected. We hypothesized that these forces would increase awards in partisan elected states relative to other states, particularly awards against out-of-state businesses. The evidence, both from the cross-state regressions and from diversity of citizenship cases, strongly supports the partisan election hypothesis. In cases involving out-of-state defendants and in-state plaintiffs, the average award (conditional on winning) is $362,988 higher in partisan than in nonpartisan states; $230,092 of the larger award is due to a bias against out-of-state defendants, and the remainder is due to generally higher awards against businesses in partisan states.

Liability System is Also Corruptible!

Suppose there is some cost X to subvert any legal institution

- Cost of bribing judges, intimidating witnesses, electing favorable legislators, etc.

If I owe Y in damages under a (tort) liability system

- If Y<X: I'll pay damages

- If Y>X: I'll subvert the system

If I owe Y in fines under a regulatory system

- If Y<X: I'll pay fines

- If Y>X: I'll subvert the system

But, regulation relies on smaller fines, tort liability relies on large but low-probability damage awards

Their conclusion: the optimal legal regime depends on the details

Show this pattern explains a lot of what happened in the US...

and also explains why tort reform has not been effective in some developing economies (and laissez-faire seems to be tolerated in some)