4.4 — Products Liability

ECON 315 • Economics of the Law • Spring 2021

Ryan Safner

Assistant Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/lawS21

lawS21.classes.ryansafner.com

Products Liability

So far, we have been assuming accidents are entirely between strangers who have no personal or economic relationship

We now turn to products liability, an subfield of tort law where the injurer is a business and the victim is a consumer of their product

- Parties have an economic relationship

Products Liability

Worth studying for three reasons

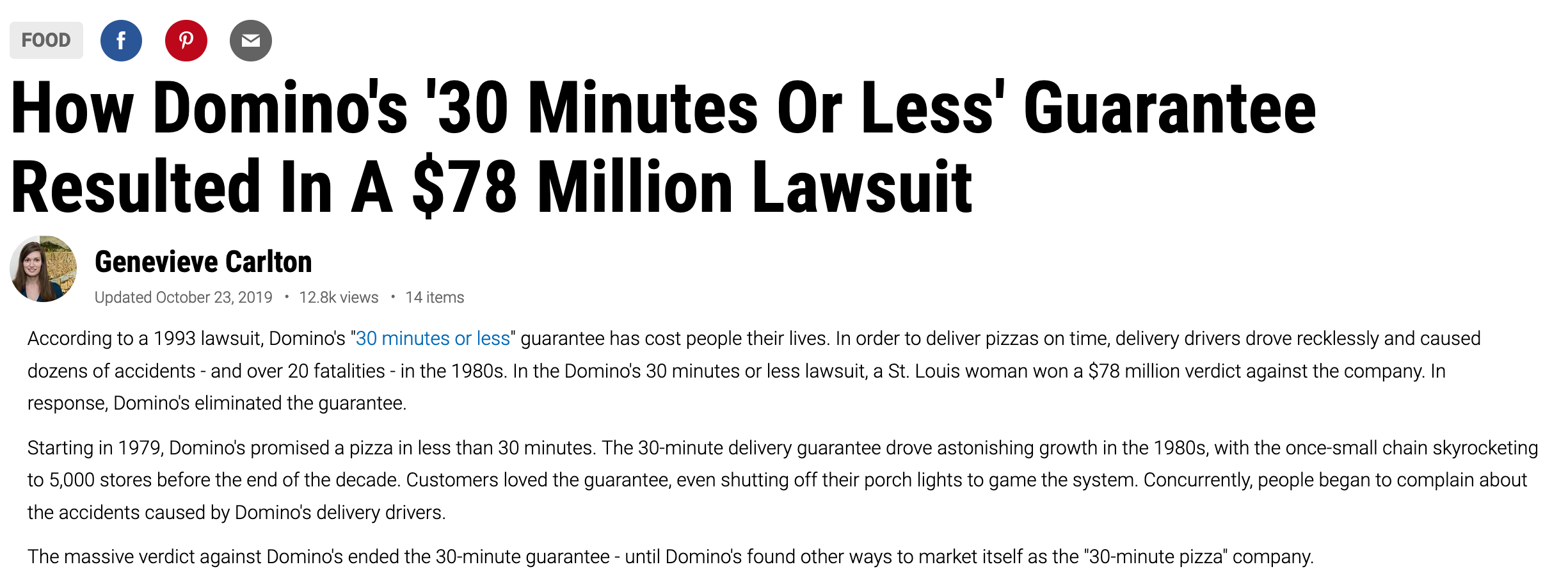

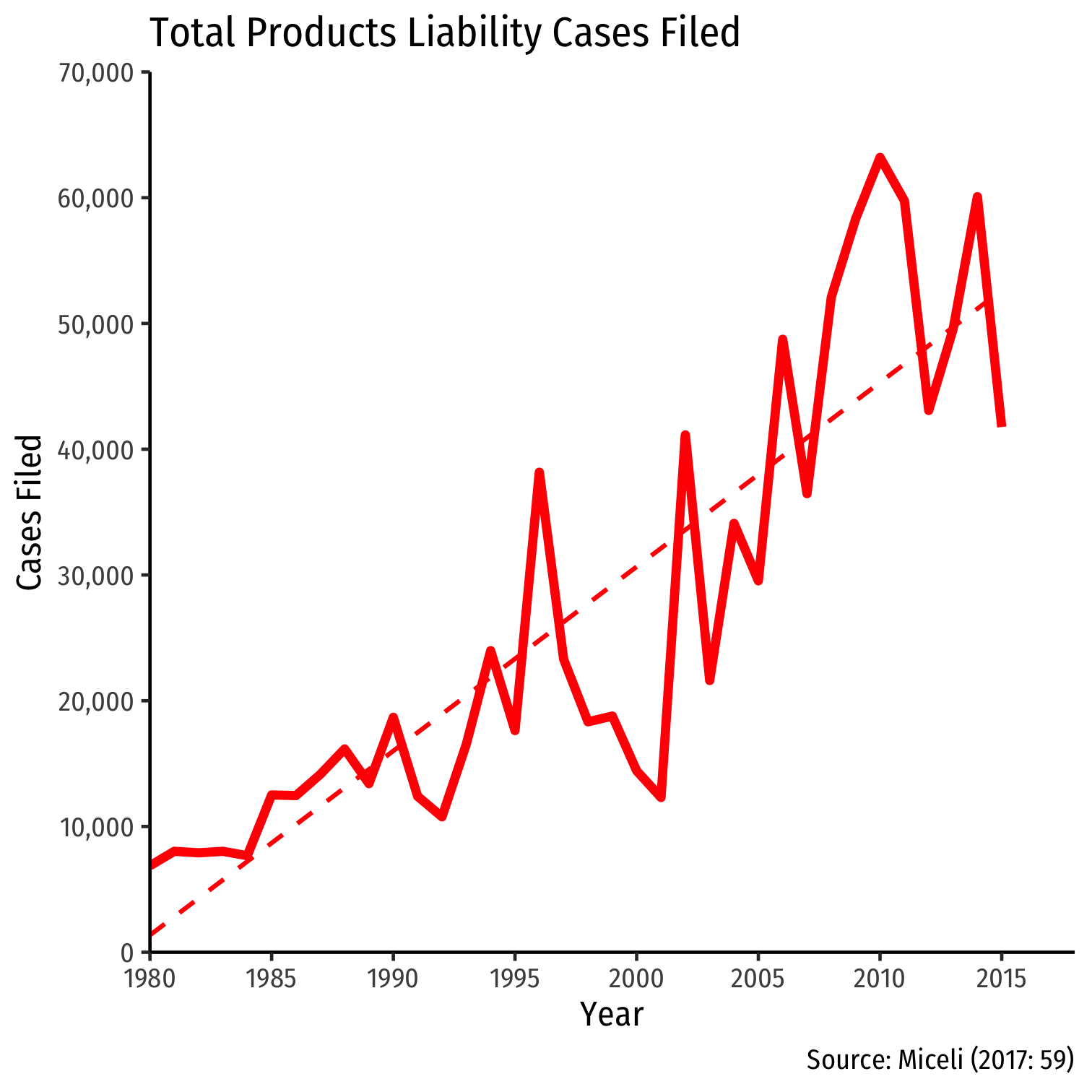

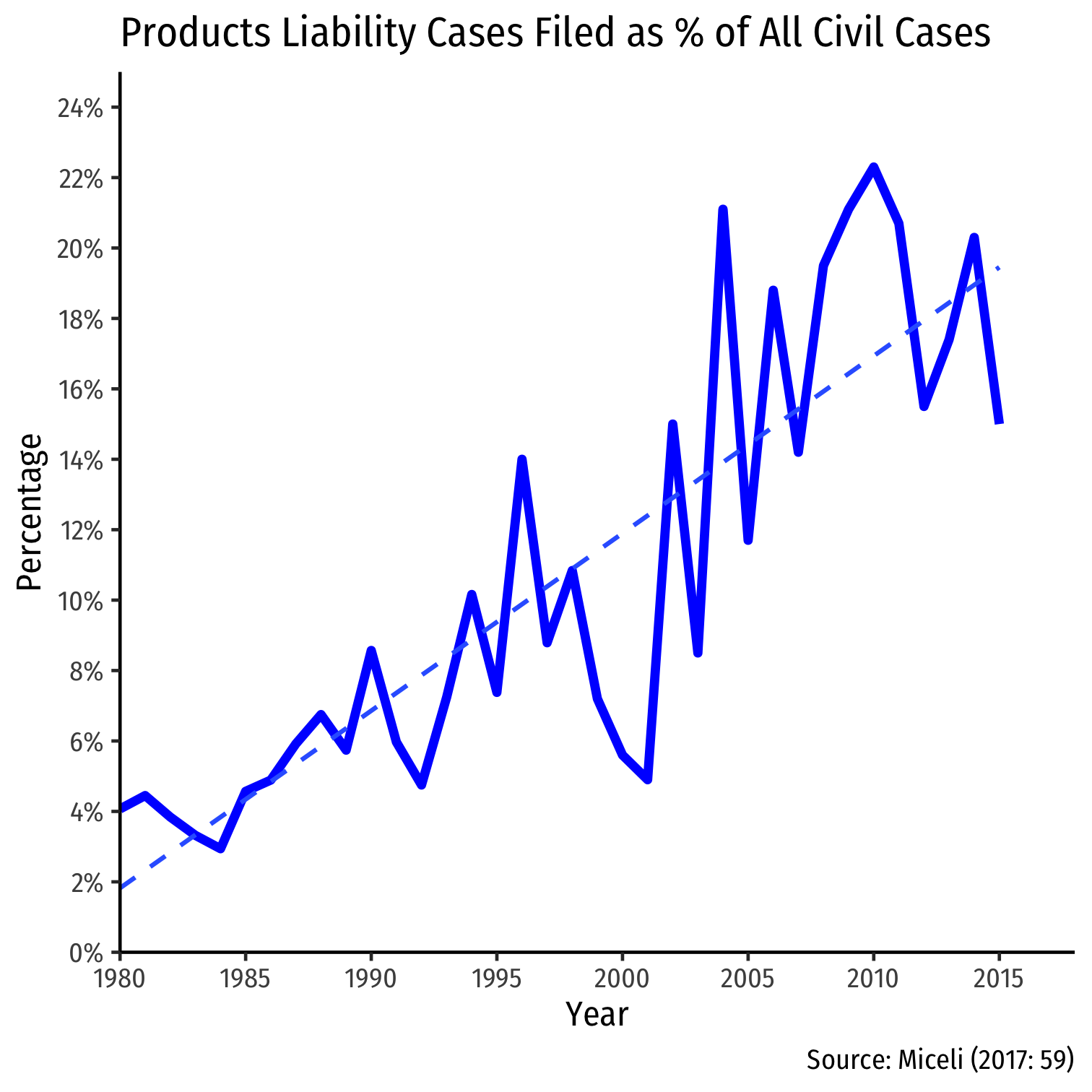

Used to be a minor type of tort case, now a major growing and specialized body of law

Source of growing dissatisfaction with our tort liability system

Accidents are between parties with a contractual relationship

- Hybrid of contract and tort law

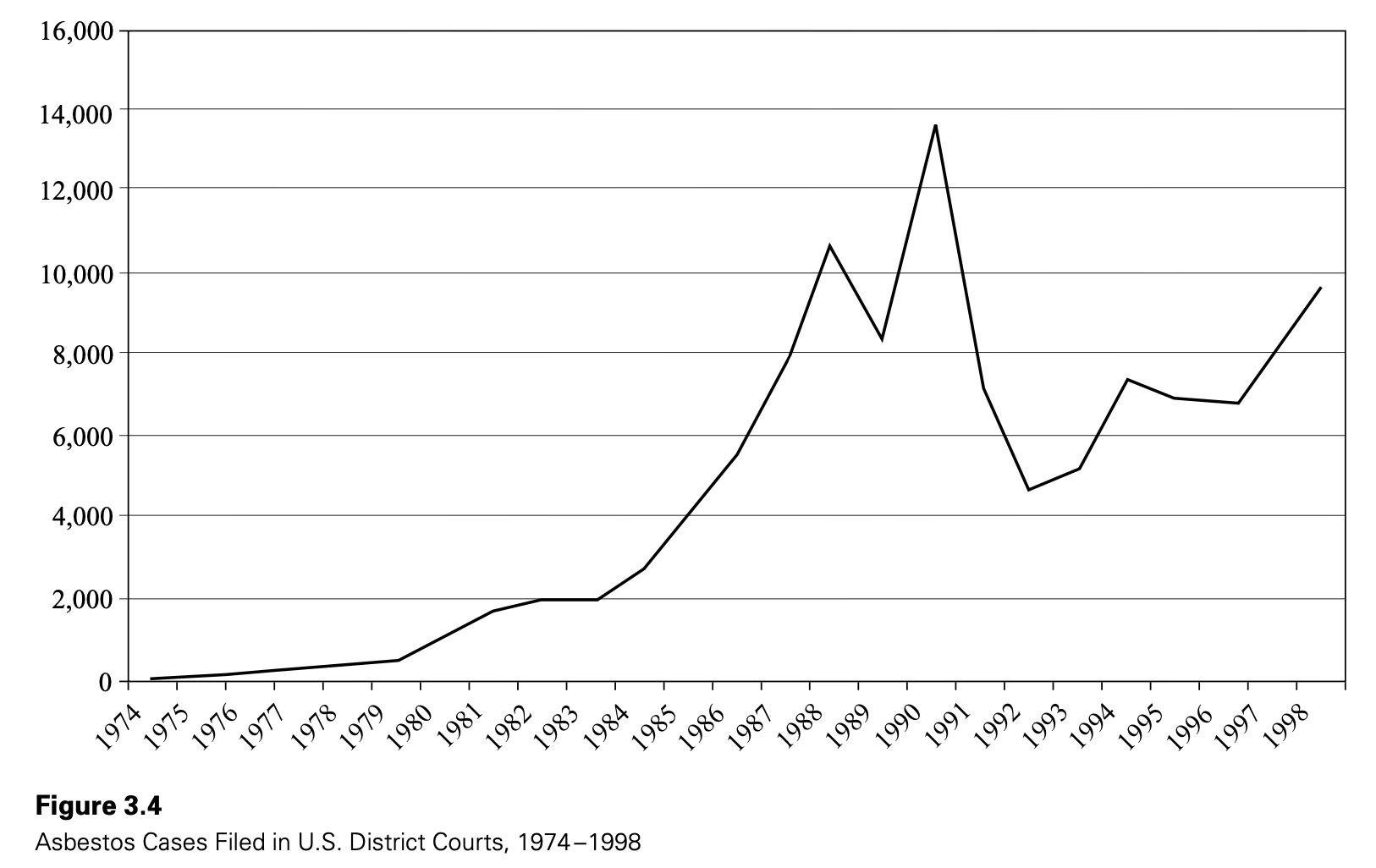

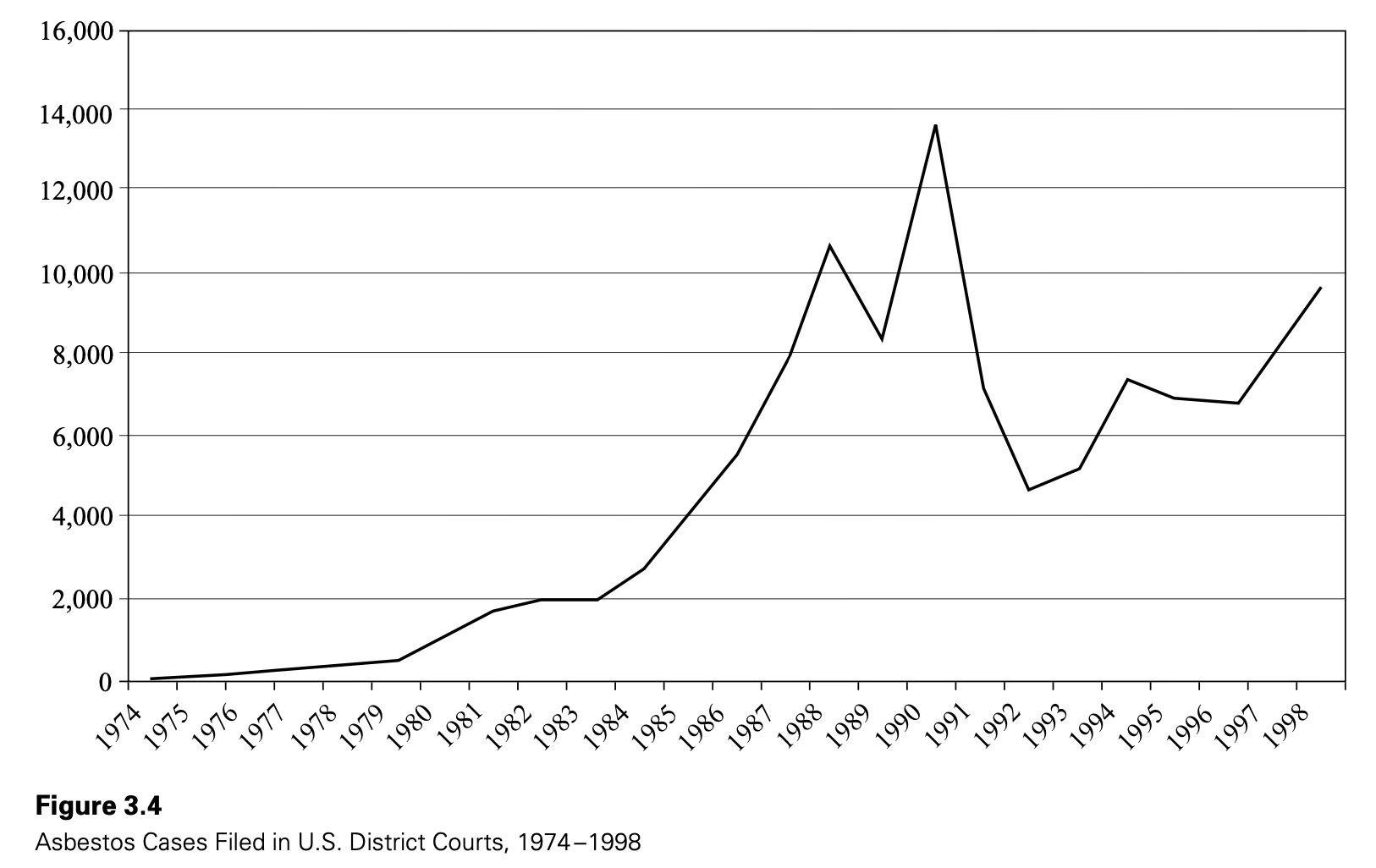

The Growth of Products Liability Cases

A Brief History of Products Liability Law

A Brief History of Products Liability Law

Three main phases of products liability law development

Corresponding to the main type of liability rule used

Pre-1916: No Liability

1916-1960: Negligence

1960—Present: Strict Liability

A Brief History of Products Liability Law

Since Industrial Revolution, focus on production and economic growth

Some suggest influence of Classical Economists (or at least, their ideas) on weak tort law against business

Some feared excessive liability for producers would threaten business

No Liability for manufacturer

- Essentially caveat emptor (buyer beware)

A Brief History of Products Liability Law

Main law in operation was contract law

Doctrine of privity of contract: only parties to a contract can sue one another

- If A and B have a contract, party C cannot sue either A or B, unless C is part of the contract

- i.e. consumer can only sue the immediate retailer from whom they purchased a product, not the product’s initial manufacturer

This effectively insulated manufacturers from liability

A Brief History of Products Liability Law

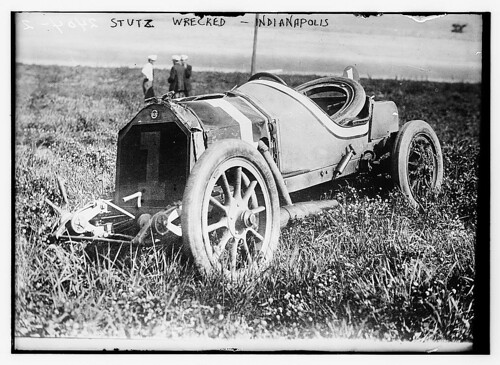

MacPherson v. Buick (217 N.Y. 382, 1916)

MacPherson had bought a Buick from a NY auto dealer, the car later lost a wheel and ejected him from the car

Buick says they have no privity with MacPherson, only with the dealership

A Brief History of Products Liability Law

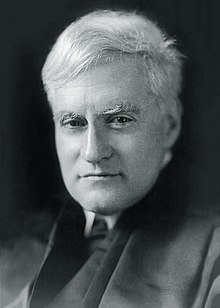

Benjamin N. Cardozo

1870—1938

Associate Justice of U.S. Supreme Court

“If the nature of a thing is such that it is reasonably certain to place life and limb in peril when negligently made, it is then a thing of danger. Its nature gives warning of the consequence to be expected. If to the element of danger there is added knowledge that the thing will be used by persons other than the purchaser, and used without new tests, then, irrespective of contract, the manufacturer of this thing of danger is under a duty to make it carefully. That is as far as we need to go for the decision of this case...If he is negligent, where danger is to be foreseen, a liability will follow.”

A Brief History of Products Liability Law

MacPherson v. Buick (217 N.Y. 382, 1916)

Court rejected privity, arguing the manufacturer could have reasonably forseen the possibility of such injuries to car’s ultimate users (consumers), and not just the immediate purchaser (dealer)

- Victim must prove negligence of the manufacturer

- MacPherson successfully showed Buick negligent

Shift from 1916—1960 to a negligence rule

- Consumer must show manufacturer was negligent in its production

A Brief History of Products Liability Law

- Final shift from negligence to strict liability occurred via two separate routes

Gradual increase in standard of due care owed by manufacturers

Increase in producer liability for breach of warranty

A Brief History of Products Liability Law

Escola v. Coca-Cola Bottling Co. (24 Cal.2d 453, 1944)

Waitress in restaurant served a Coca-cola bottle that spontaneously exploded, causing injuries

Plaintiff could not offer any evidence that Coca Cola was negligent in its production

A Brief History of Products Liability Law

Majority opinion (Chief Justice Phil S. Gibson):

“Upon an examination of the record, the evidence appears sufficient to support a reasonable inference that the bottle here involved was not damaged by any extraneous force after delivery to the restaurant by defendant. It follows, therefore, that the bottle was in some manner defective at the time defendant relinquished control, because sound and properly prepared bottles of carbonated liquids do not ordinarily explode when carefully handled.”

A Brief History of Products Liability Law

Concurring opinion (Justice Roger Traynor):

“[Public policy demands] responsibility be fixed wherever it will most effectively reduce the hazards to life and health inherent in defective products that reach the market...In leaving it to the jury to decide whether the inference has been dispelled, regardless of the evidence against it, the negligence rule approaches the rule of strict liability. It is needlessly circuitous to make negligence the basis of recovery and impose what is in reality liability without negligence. If public policy demands that a manufacturer of goods be responsible for their quality regardless of negligence there is no reason not to fix that responsibility openly.”

A Brief History of Products Liability Law

Escola v. Coca-Cola Bottling Co. (24 Cal.2d 453, 1944)

Court held Injurer liable under legal doctrine of res ipsa loquitor (“the thing speaks for itself”)

- Evidence of the accident alone is sufficient to hold injurer liable

- Only a defective Coke bottle would explode

As due care does not entirely eliminate the risk of accidents under this rule, effectively a rule of strict liability for the Injurer

- Modern production makes it too difficult for consumers to inspect or verify the product is safe; strict liability more practical

A Brief History of Products Liability Law

In contract law, sellers are strictly liable for damages caused by products that fail to operate as presented (regardless of negligence), a breach of warranty

However, privity of contract operates here — only those who are a party to the contract may sue (essentially for breach of contract)

A Brief History of Products Liability Law

Henningsen v. Bloomfield Motors, Inc. (32 N.J. 358, 1960)

Henningsen bought a Chrysler car from Bloomfield Motors (an auto dealer)

Steering mechanism in Henningsen’s Chrysler car failed, causing an accident

Sale contract between Henningsen’s and the manufacturer expressly limited Chrysler’s liability to the original purchaser (dealer), and only for certain types of damages (defective parts, etc.)

- Contract stipulated no express or implied warranty to customer

A Brief History of Products Liability Law

Court rejected this limitation, arguing implied warranty of fitness prevailed regardless of any expressed contractual terms to the contrary

- Additionally, struck down the privity doctrine

Although the victim was not the original purchaser, she:

“in the reasonable contemplation of the parties to the warranty, might be expected to become a user of the automobile. Accordingly, her lack of privity does not stand in the way of prosecution of the injury suit against the defendant Chrysler.”

- So now both tort and contract law converge to a strict liability standard for manufacturers

A Brief History of Products Liability Law

- The Restatement (Second) of Torts 1965

(\S)402A:

(1) One who sells any product in a defective condition unreasonably dangerous to the user or consumer or to his property is subject to liability for physical harm thereby caused to the ultimate user or consumer, or to his property, if

(a) the seller is engaged in the business of selling such a product, and

(b) it is expected to and does reach the user or consumer without substantial change in the condition in which it is sold.

(2) The rule stated in Subsection (1) applies although

(a) the seller has exercised all possible care in the preparation and sale of the product, and

(b) the user or consumer has not bought the product from or entered into any contractual relation with the seller.

- Note that part (2)(a) excludes consideration of producer care (hence, liability is strict), part (2)(b) eliminates privity

Strict Liability for Manufacturers?

Somewhat misleading to label the rule as “strict liability”

In addition to harm & causation, Plaintiffs must show product is defective in design or manufacture

Or, if it is inherently dangerous, the manufacturer failed to warn consumers of danger

- e.g. cigarettes, dynamite, lithium ion batteries

Strict Liability for Manufacturers?

- Element of negligence here: manufacturers can avoid liability by meeting the design standard or the duty to warn

- Though courts are still becoming more strict in determining whether or not Defendants meet these standards

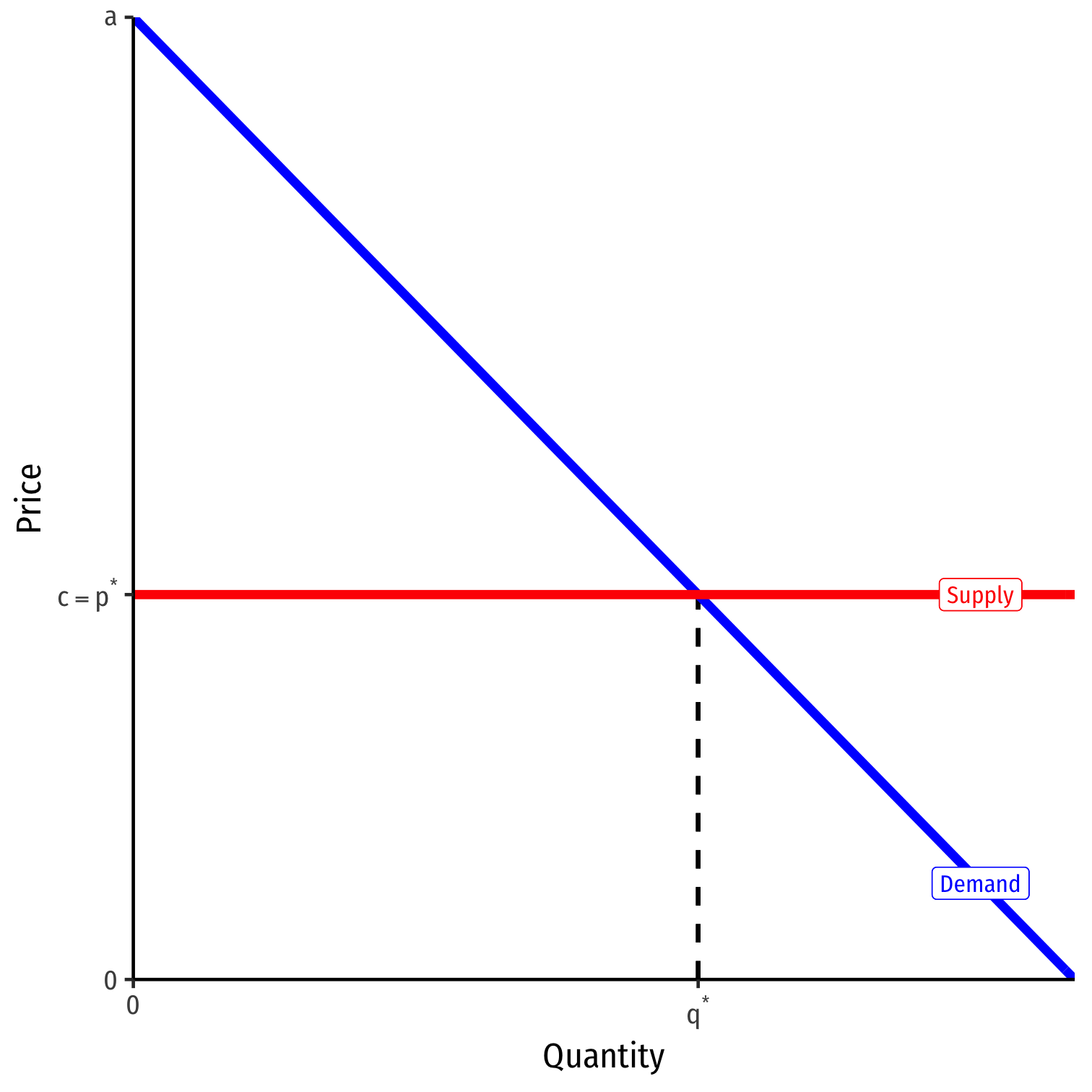

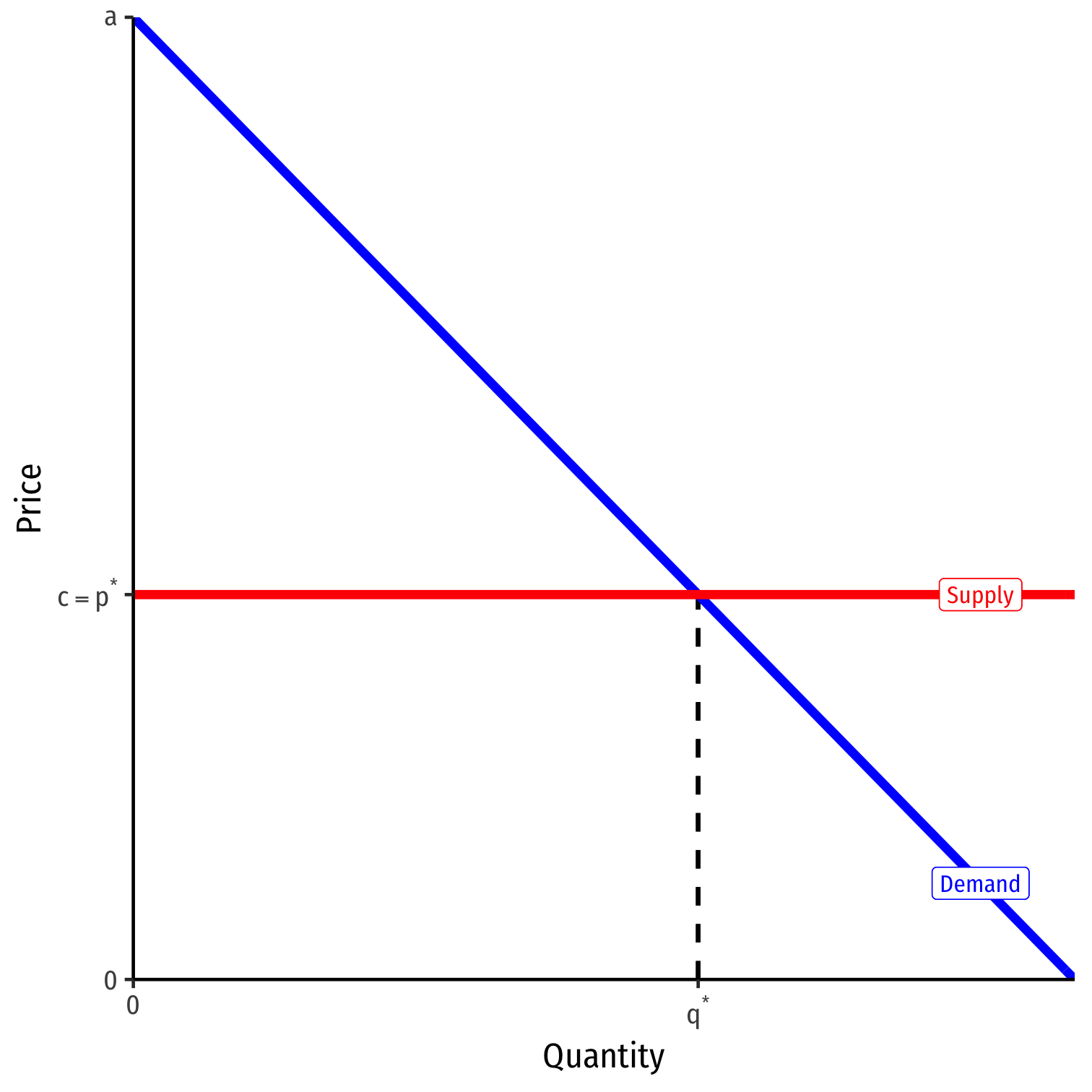

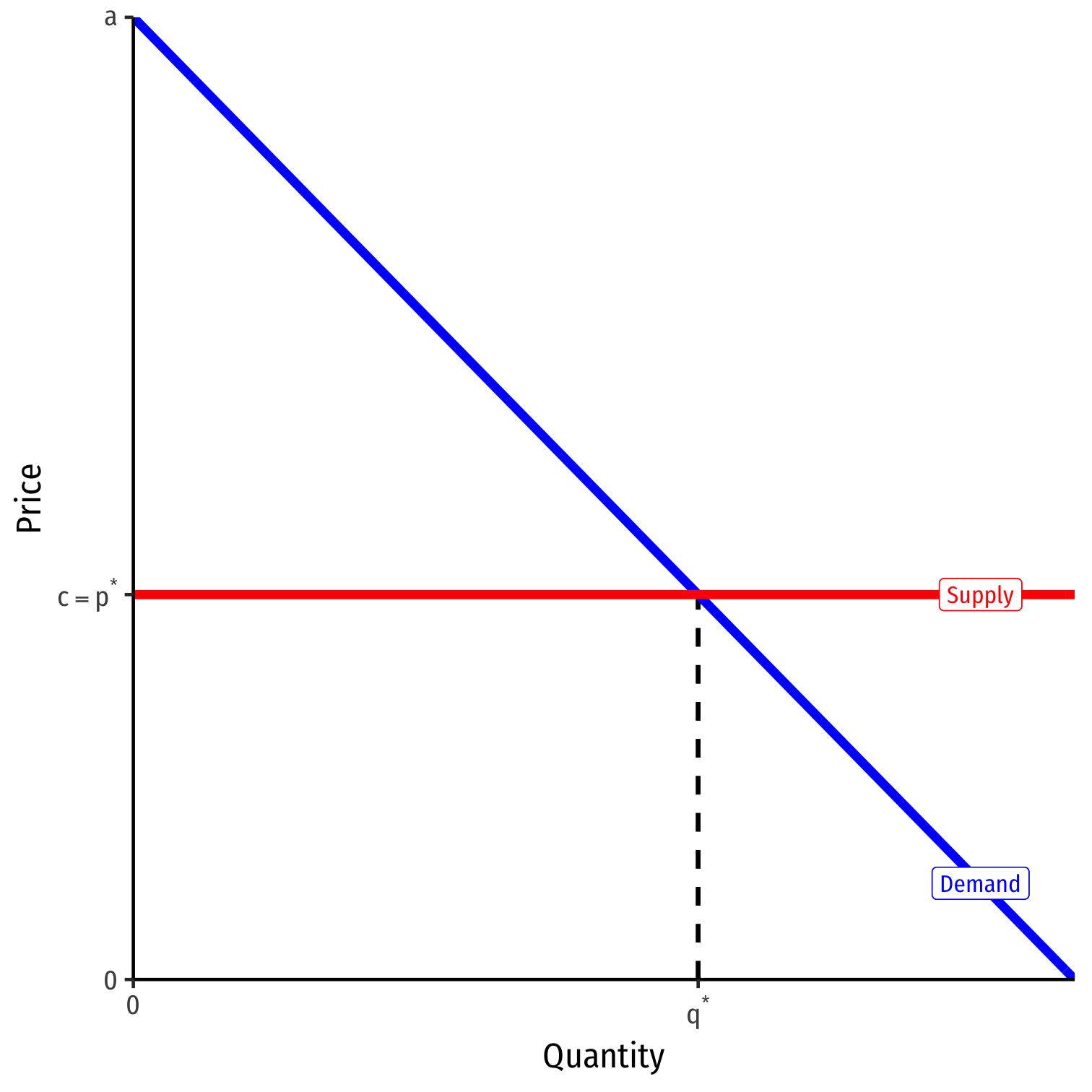

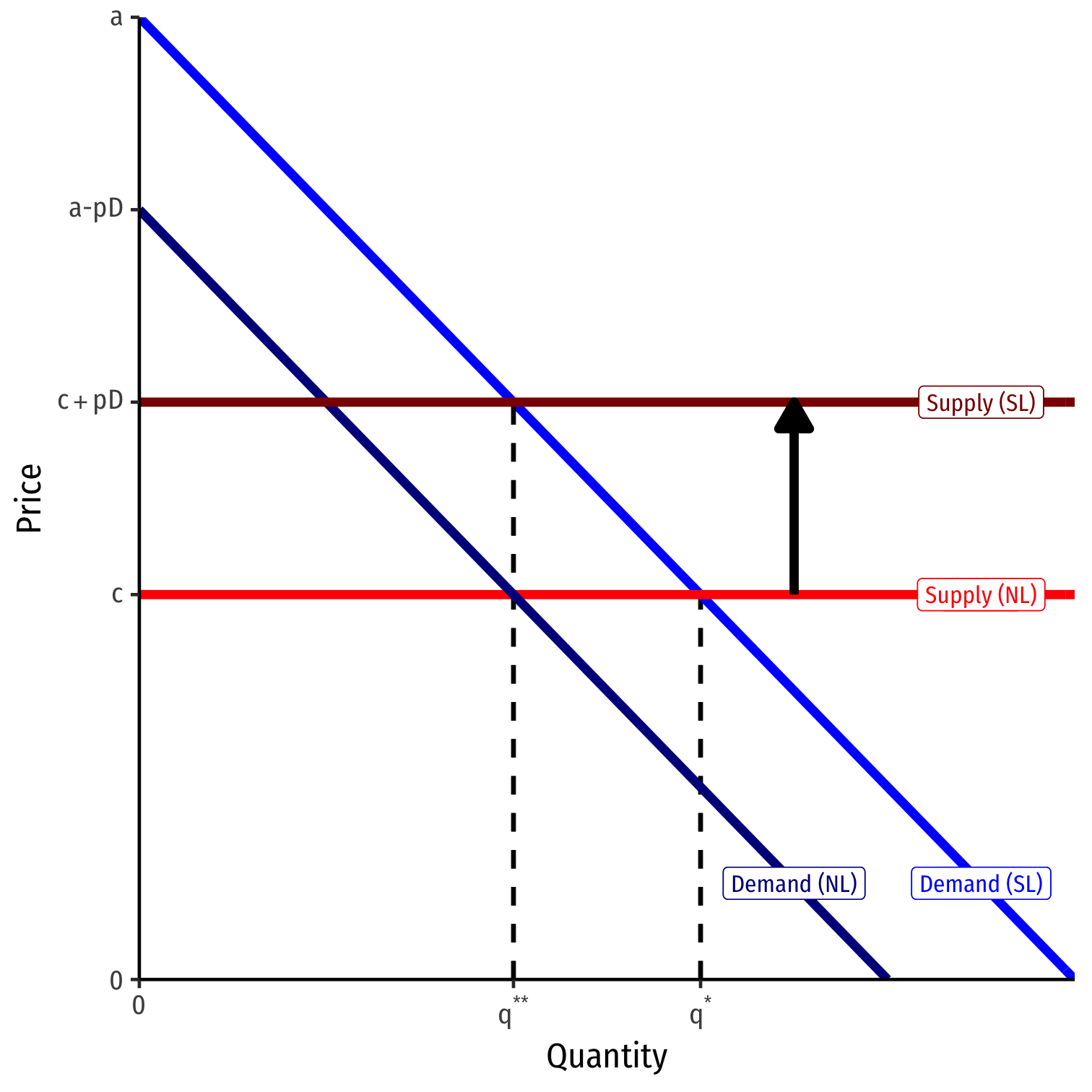

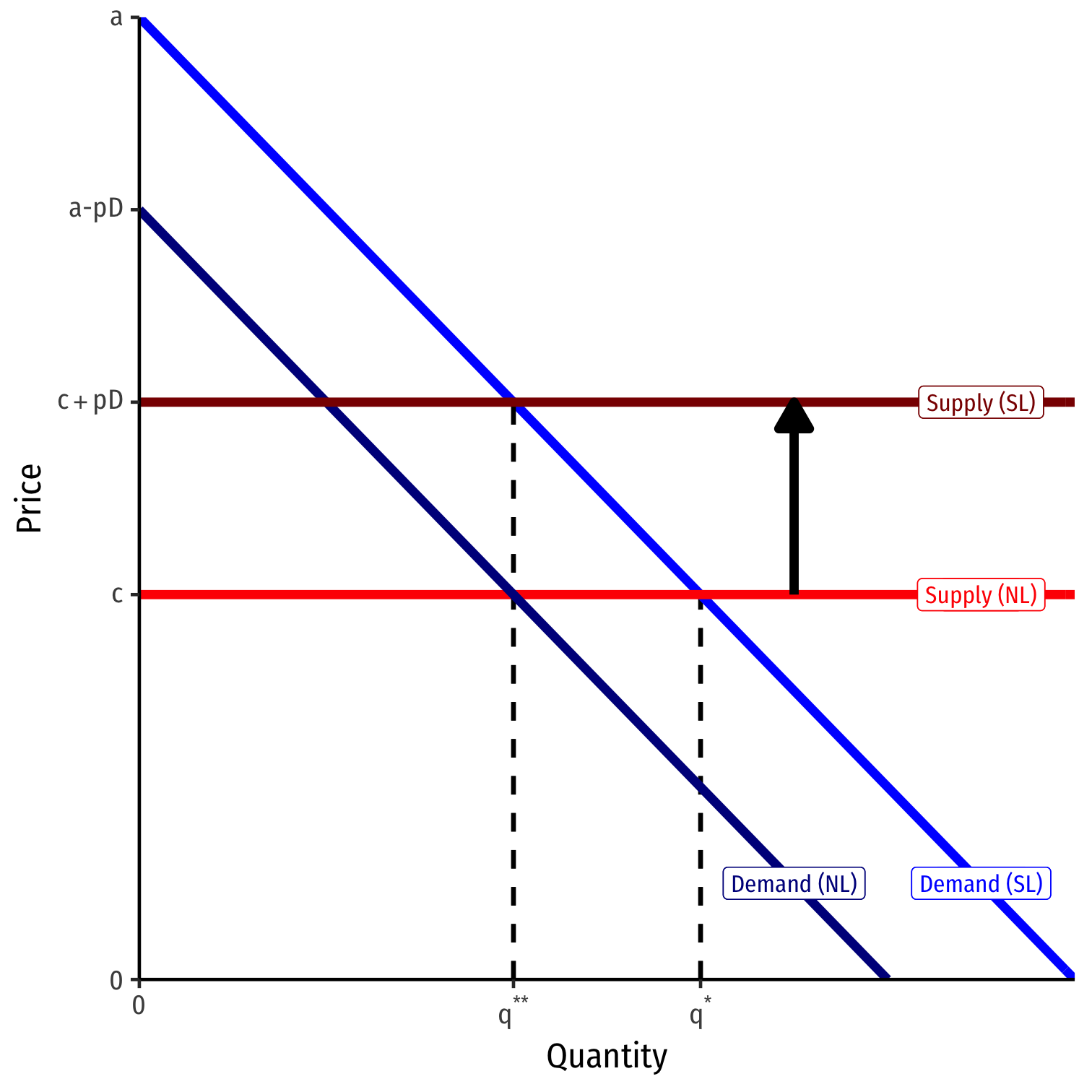

A Simple Economic Model of a Risky Product

A Simple Economic Model of a Risky Product

Consider a typical supply and demand model, first for a safe product

Demand: p=a−bq

- marginal benefit to consumer

- a: choke price (intercept)

- b: slope

Supply: p=c

- c is marginal cost

Equilibrium (q⋆,p⋆) q⋆=c+ba;p⋆=c

A Simple Economic Model of a Risky Product

Consider a typical supply and demand model, first for a safe product

Demand: p=a−bq

- marginal benefit to consumer

- a: choke price (intercept)

- b: slope

Supply: p=c

- c is marginal cost

Equilibrium (q⋆,p⋆) q⋆=c+ba;p⋆=c

A Simple Economic Model of a Risky Product

Now suppose the product comes with some risk of an accident

- p: probability of accident (per unit)

- D: damages from accident

- pD: expected damages (per unit)

- pDq: total expected damages

Accidents are determined by both parties’:

- care levels (e.g. x and y from before)

- activity levels

A Simple Economic Model of a Risky Product

We need to consider the liability rule in place

- s: manufacturer’s share of liability

- 1-s: consumer’s share of liability

Two main alternatives:

- s=1: strict liability (SL)

- s=0: no liability (NL)

A Simple Economic Model of a Risky Product

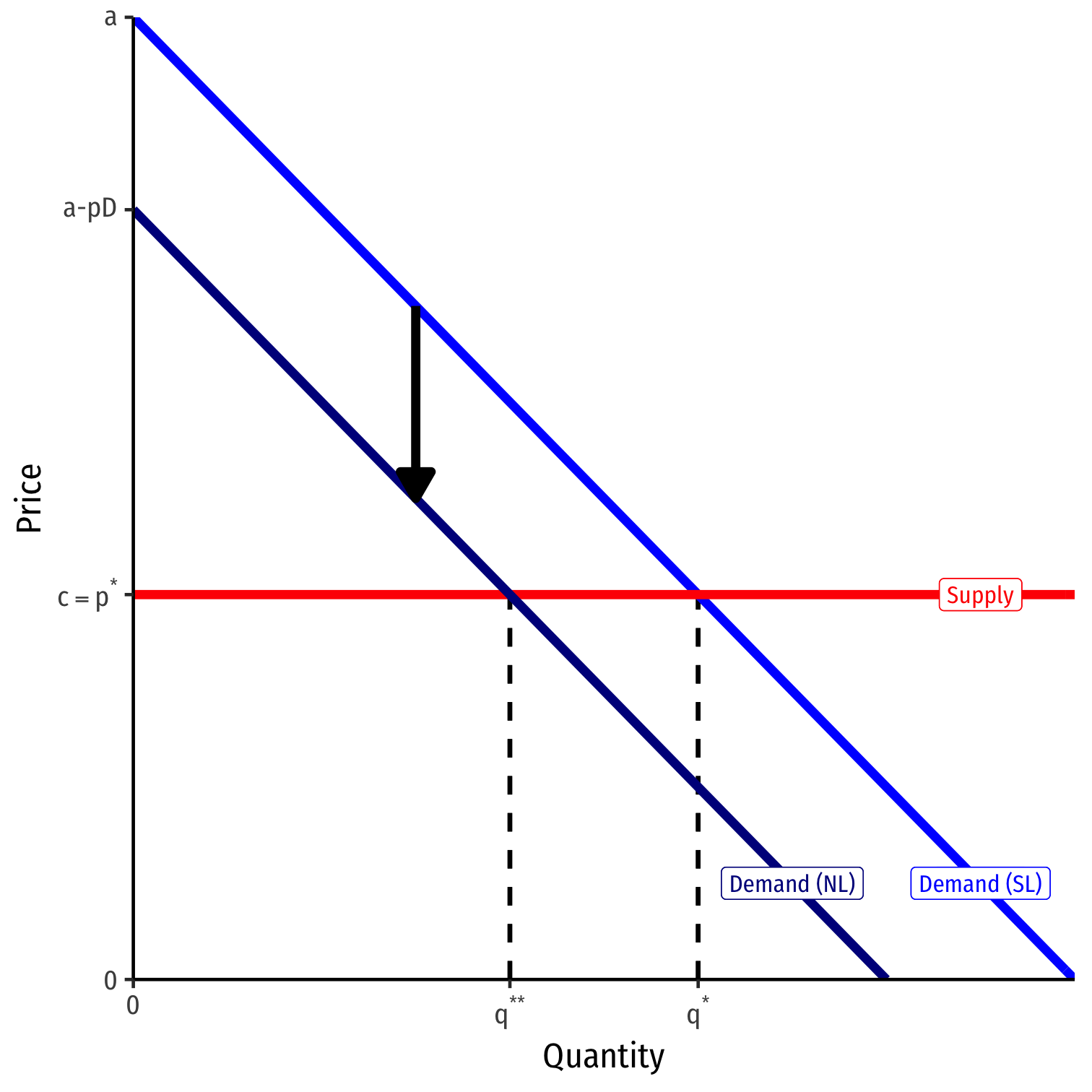

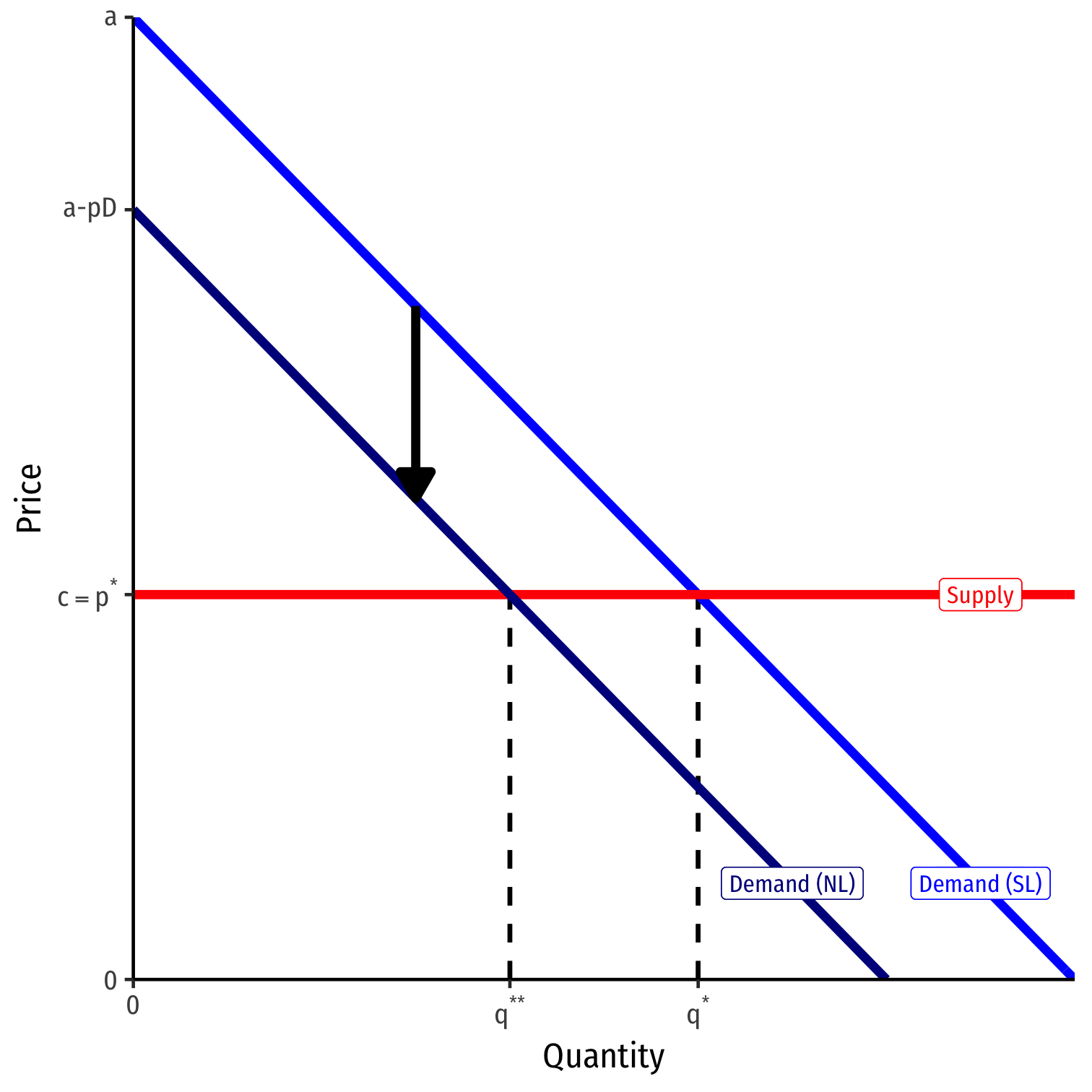

Now adjust Demand and Supply to account for accident risk, determined by liability:

Demand with risk: p=a−bq−(1−s)pD

- a−bq: marginal benefit (WTP) ignoring risk

- (1−s)pD: discounting by consumer’s expected liability

A Simple Economic Model of a Risky Product

Demand with risk: p=a−bq−(1−s)pD

If s=1 (SL), no change in demand, consumer behaves as if product was perfectly safe

- p=a−bq

- Fully insured against any risk (manufacturer is strictly liable)

If s=0 (NL), reduce spending exactly by expected damages per unit

- Consumer full bears the risk of accident

A Simple Economic Model of a Risky Product

Now adjust Demand and Supply to account for accident risk, determined by liability:

Supply with risk p=c+spD

- c: marginal cost ignoring risk

- spD: premium for seller’s expected liability

A Simple Economic Model of a Risky Product

Now adjust Demand and Supply to account for accident risk, determined by liability:

Supply with risk p=c+spD

If s=0 (NL), no change in supply, producer behaves as if product was perfectly safe

- Fully insured against any risk (caveat emptor, consumer incurs full cost)

If s=1 (SL), raise asking price exactly by expected damages per unit

- Seller fully bears the risk of accident

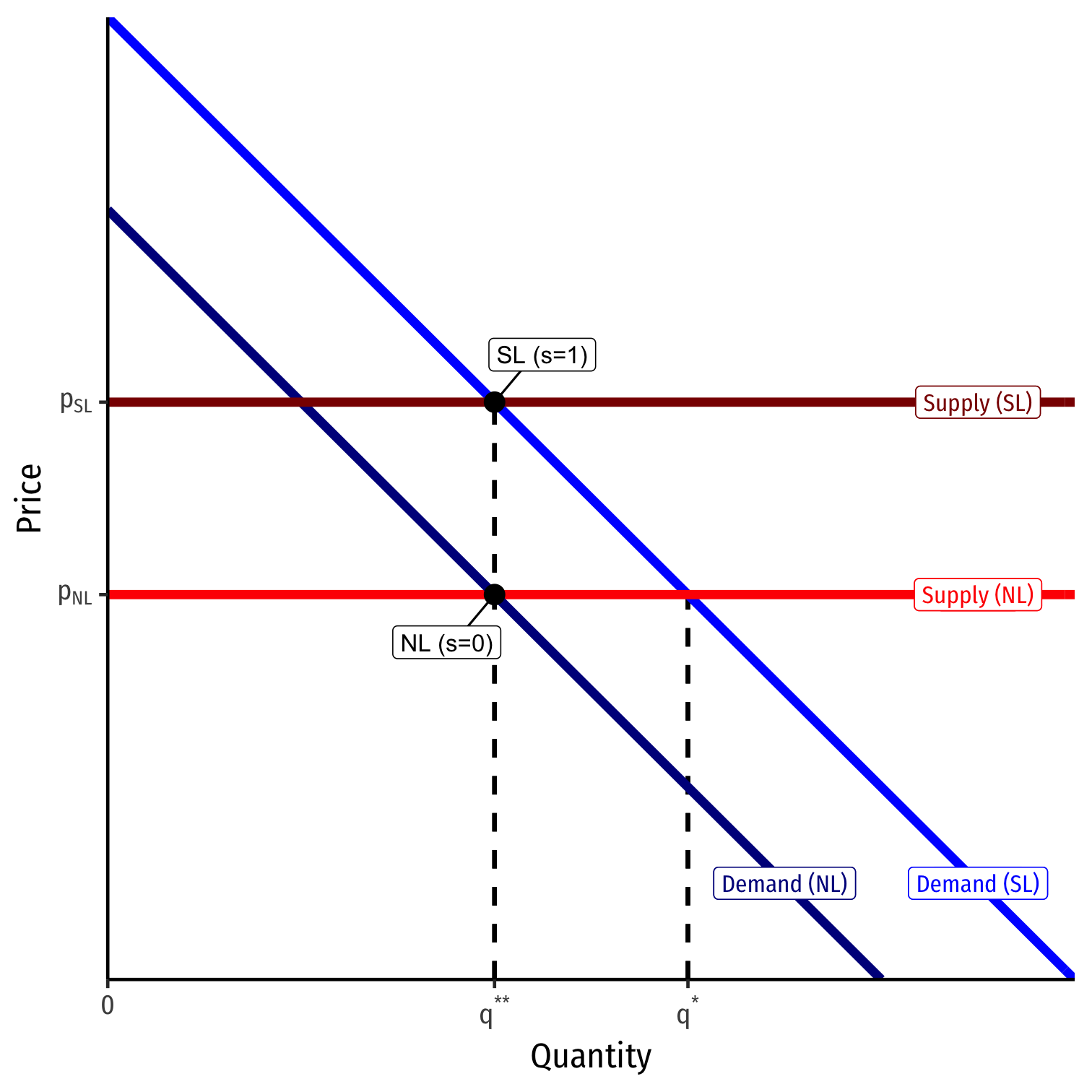

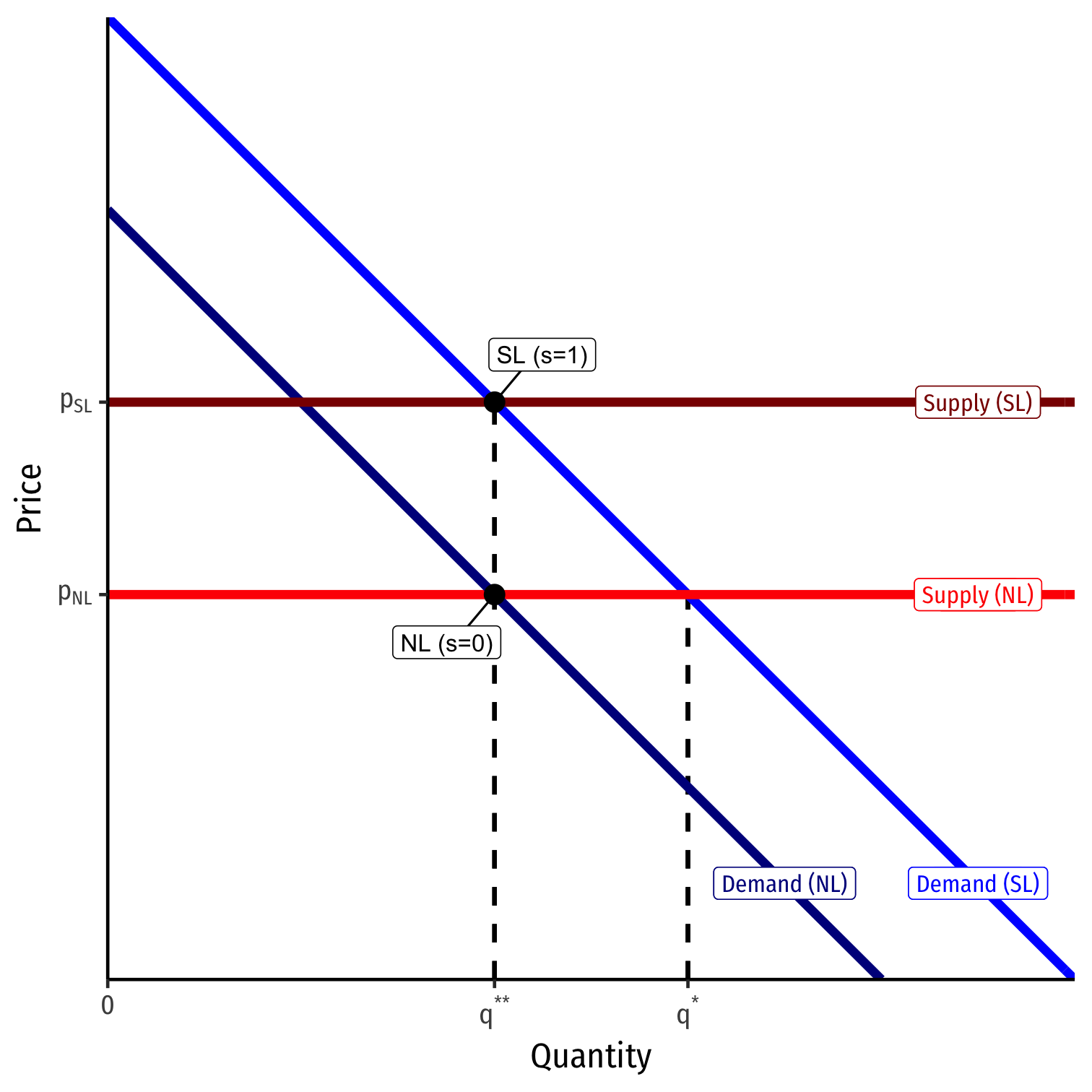

A Simple Economic Model of a Risky Product

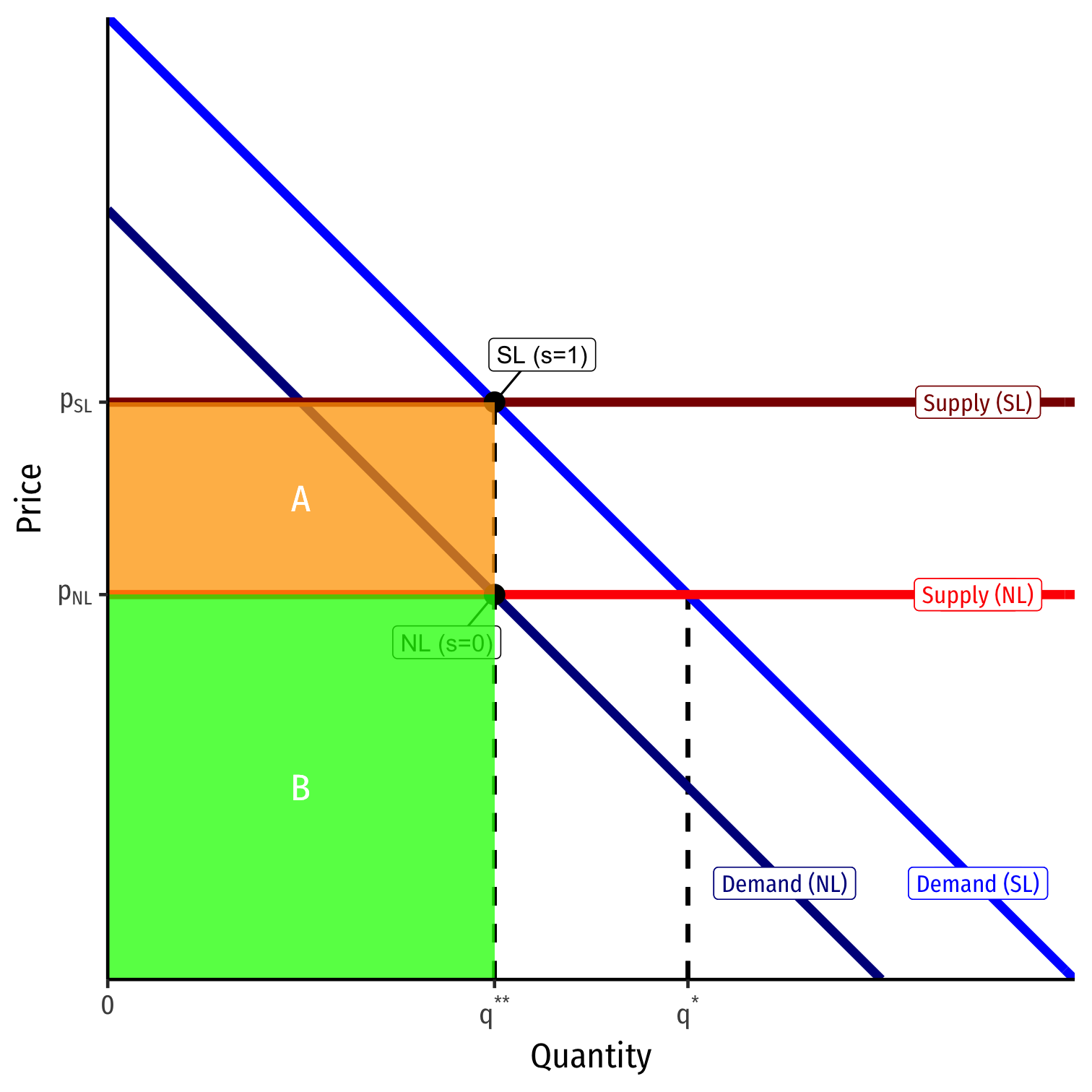

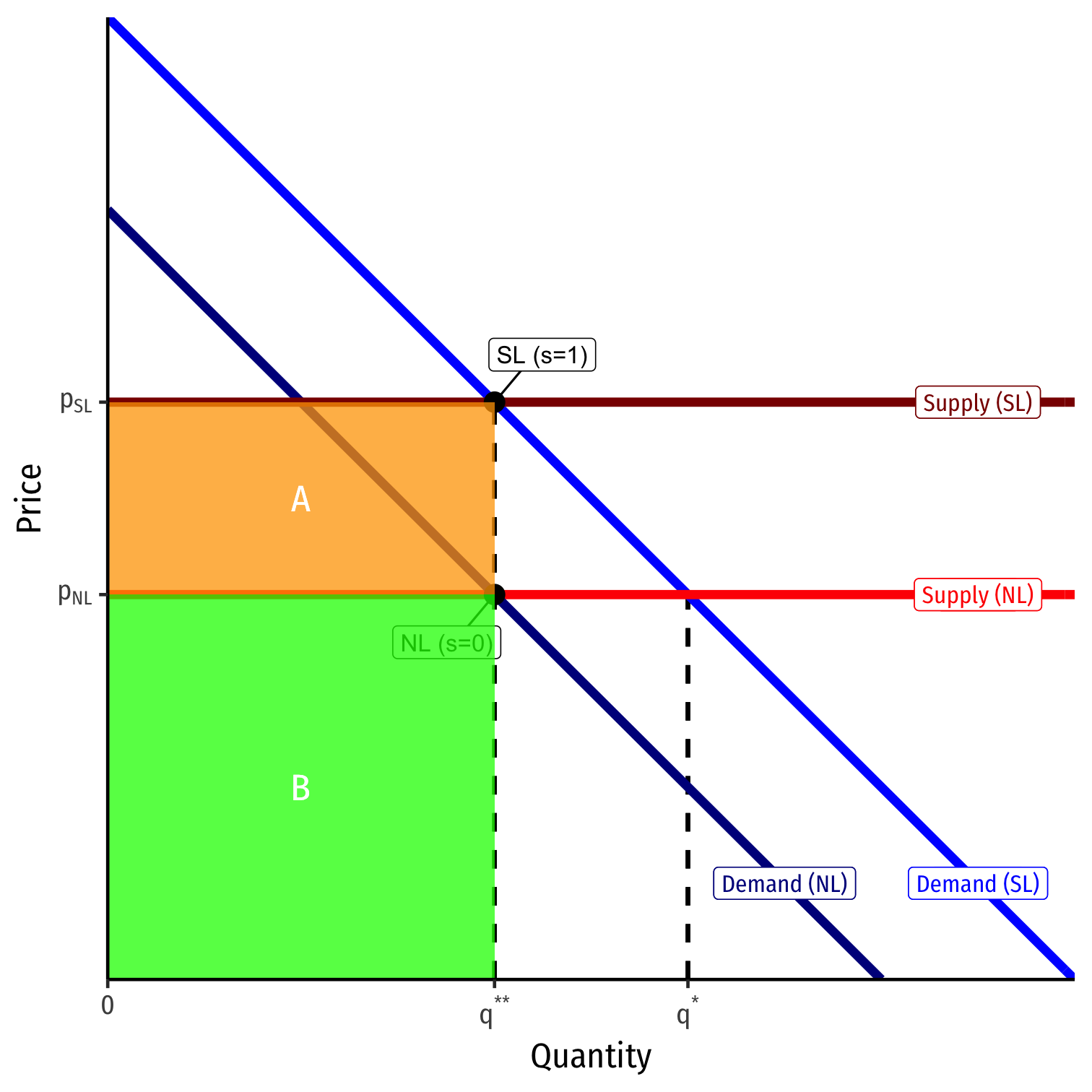

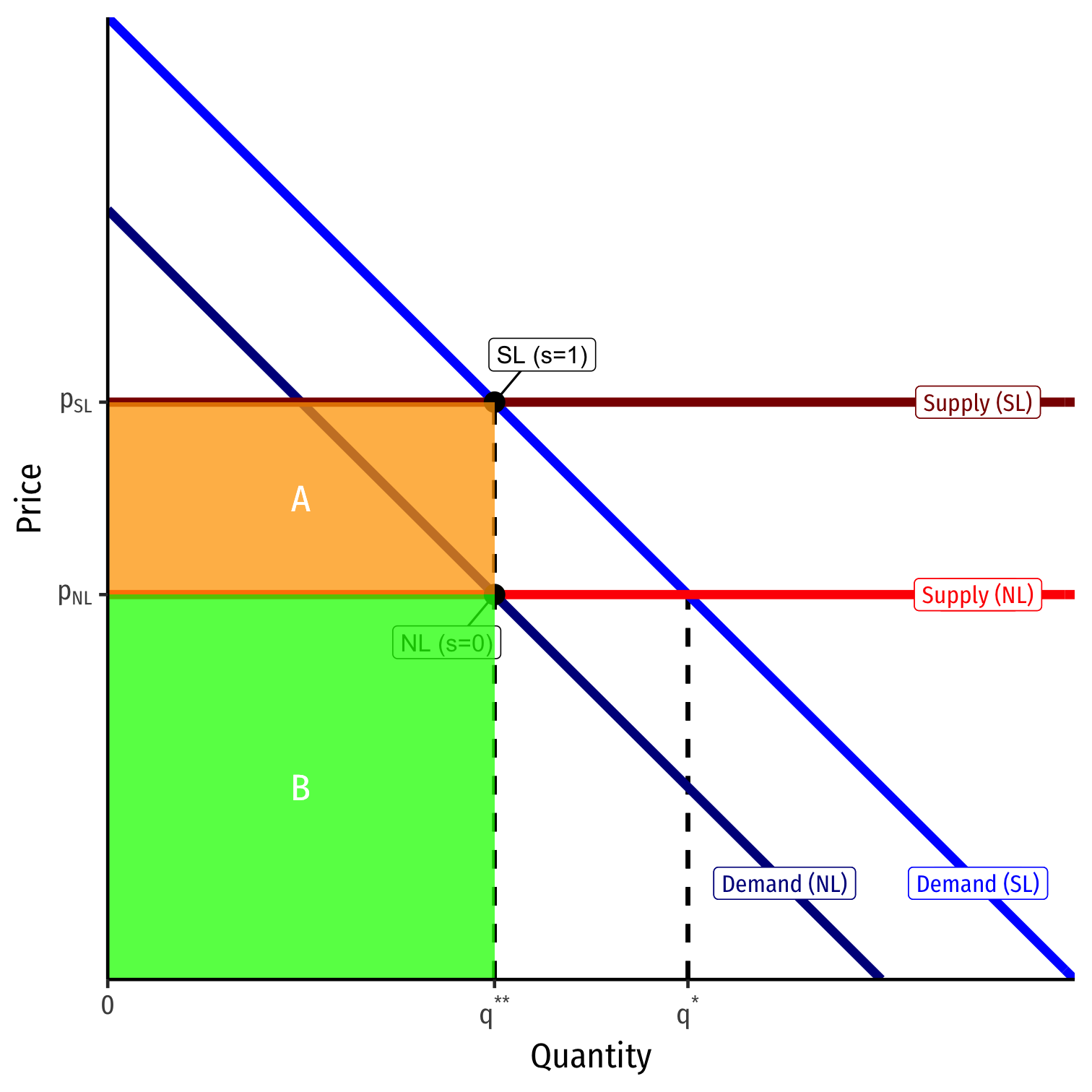

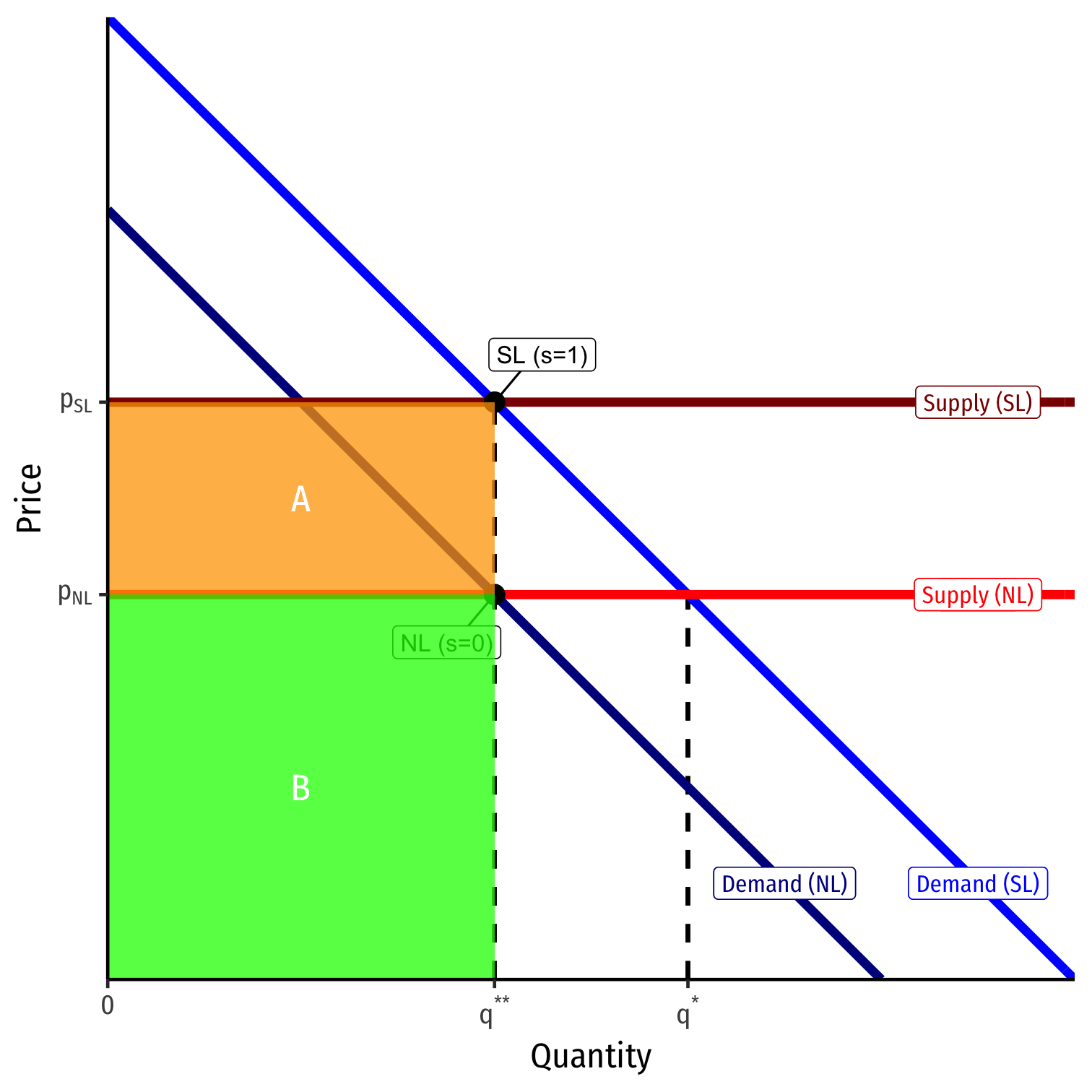

Regardless of the rule (s), equilibrium quantity is always q⋆⋆! a−b(q)−(1−s)pD=c+spDa−b(q)=c+pD

q⋆⋆ efficient level where marginal social benefit = full marginal social cost (including expected accident costs)

Application of the Coase Theorem: resource allocated efficiently (MSB=MSC) regardless of the assignment of liability!

- Main reason is liability is shifted via price (see next)

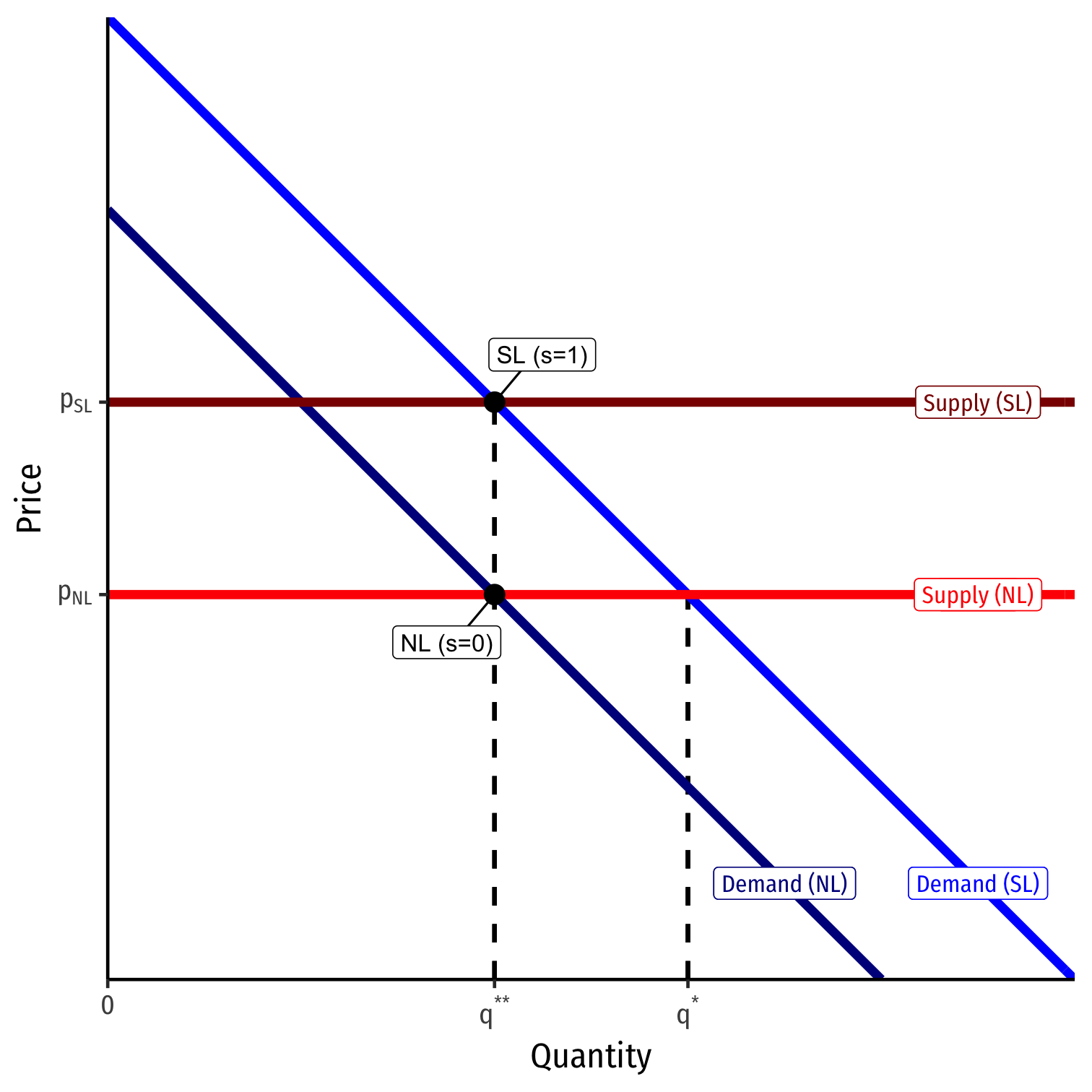

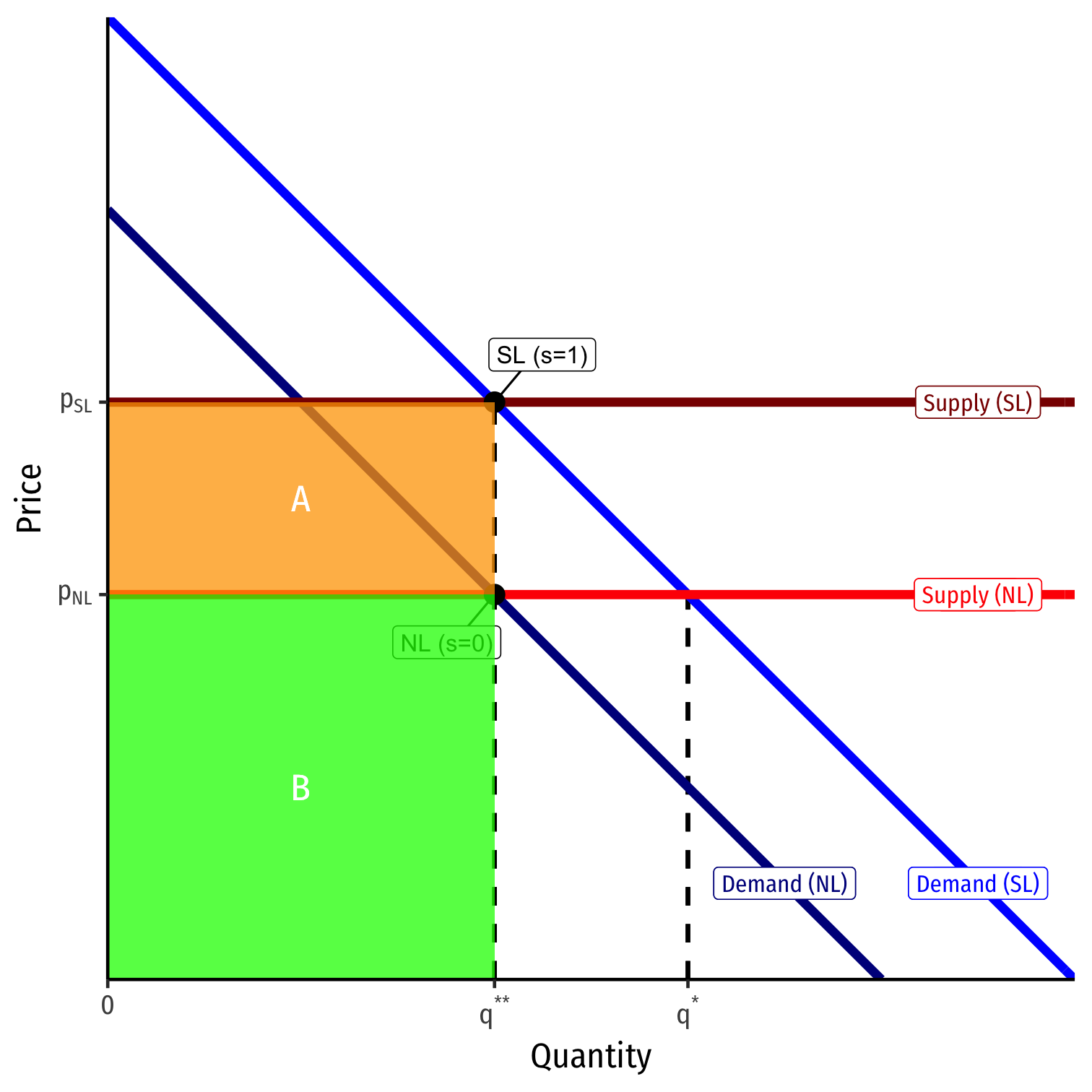

A Simple Economic Model of a Risky Product

The price of the product does depend on rule s:

- When s=0 (No Liability), p=pNL

- When s=1 (Strict Liability), p=pSL

Area B = cq⋆⋆=pNLq⋆⋆

- cost & revenue to seller

Area A = pDq

- total expected damages, an additional cost

Area B + A = total social costs to produce (under Strict Liability s=1)

A Simple Economic Model of a Risky Product

Producer will always directly bear area B as cost (MC of production)

Liability rule s will determine who will bear cost of area A

- No liability (s=0): consumer bears full cost of A

- Strict liability (s=1): producer bears full cost of A

- raises the price to pSL to collect cost upfront

A Simple Economic Model of a Risky Product

- Under a rule of no liability (s=0) (caveat emptor), consumer self-insures

- decides how much to allocate extra savings of (not paying) area A (lower price pNL)

- save money, take out insurance, buy a different product, etc. to prepare for expected damages pD

A Simple Economic Model of a Risky Product

- Under strict liability (s=1), producer pays production costs B + expected liability costs A

- sells product bundled with an “insurance policy”

- (pSL−pNL): “insurance premium”

- law incentivizes producers to insure consumers against risk

A Simple Economic Model of a Risky Product

The main question is, who is the better insurer?

- Self-insurance at price pNL

- Manufacturer bundles good and insurance at price pSL

If accident happens with first unit

- Consumer has not built up enough savings, far better to purchase insurance in market rather than self-insure

- Same issue with (small) firms, usually also purchase insurance in market to cover expected tort liability under SL

Risky Products: Precaution Incentives

Risky Products: Precaution Incentives

Will the level of precaution be optimal regardless of the liability rule? (like output q⋆⋆)?

- Coase Theorem implies yes

If s=0 (no liability)

- In model of accidents between strangers (lesson 3.2), we saw victims take efficient care y=y⋆ and injurers take no care x=0

- In today's model, suppose manufacturer & consumer bargain: manufacturer agrees to produce safe product in return for higher price pSL

- Manufacturer will invest in efficient safety level: where MB of reduction in accidents = MC

Risky Products: Precaution Incentives

Will the level of precaution be optimal regardless of the liability rule? (like output q⋆⋆)?

- Coase Theorem implies yes

If s=1 (strict liability)

- In model of accidents between strangers (lesson 3.2), we saw injurers take efficient care x=x⋆ and victims take no care y=0

- In today's model, suppose manufacturer & consumer bargain: ,blue[consumer] promises to use product carefully in exchange for a price reduction by manufacturer (pNL)

- Consumer will use product safely in an efficient way: where MB of reduction in accidents = MC

Both lead to safer products, assuming low transaction costs

Risky Products: Precaution Incentives

How likely are these to work in practice?

First case (no liability), consumer pays higher price if she can see product is safer

- sometimes consumers can't inspect & determine safety at purchase (e.g. drugs)

Second case (strict liability) is virtually impossible

- consumer has to live up to their long-term promise to use product safely

- Manufacturer can't monitor consumer's behavior, hence, unwilling to make this bargain

Risky Products: Precaution Incentives

Coase theorem fails with these high transaction costs

- liability rule s now very relevant

- back to a world of strangers in accidents with other strangers

We saw a strict liability rule is unlikely to achieve efficient level of victim (consumer) care

Further complicates matters if (as they often do), consumers mispercieve risks

- Empirical evidence that people overestimate low probability risks and underestimate high probabiliy risks

- Product accidents primarily are the first case

Consumer Misperceptions of Risk

Return to our model, let's first look at equilibrium output

Producers correctly perceive probability of accident as p

- Have better knowledge about its risk

Suppose consumers misperceive the probability of an accident as αp

- α=1: true probability

Consumer Misperceptions of Risk

Return to our model, let's first look at equilibrium output

Producers correctly perceive probability of accident as p

- Have better knowledge about its risk

Suppose consumers misperceive the probability of an accident as αp

- α=1: true probability

- α>1: overestimate probability

- α<1: underestimate probability

Consumer Misperceptions of Risk

- Now Demand under any legal rule:

a−b(q)−(1−s)αpD

Consumer Misperceptions of Risk

- Now Demand under any legal rule:

a−b(q)−(1−s)αpD

- Supply under any legal rule remains:

c+spD

Consumer Misperceptions of Risk

- Now Demand under any legal rule:

a−b(q)−(1−s)αpD

- Supply under any legal rule remains:

c+spD

- Setting these equal, equilibrium output is:

a−b(q)−(1−s)αpD=c+spD

- If α=1, then output is q⋆⋆

Consumer Misperceptions of Risk

- Now Demand under any legal rule:

a−b(q)−(1−s)αpD

- Supply under any legal rule remains:

c+spD

- Setting these equal, equilibrium output is:

a−b(q)−(1−s)αpD=c+spD

- If α=1, then output is q⋆⋆

- Recall if s=1, then equilibrium is q⋆⋆ where a−b(q)=c+pD

--

- If α≠1, then for any liability rule other than strict liability (s<1), output will not be the efficient level q⋆⋆!

Consumer Misperceptions of Risk

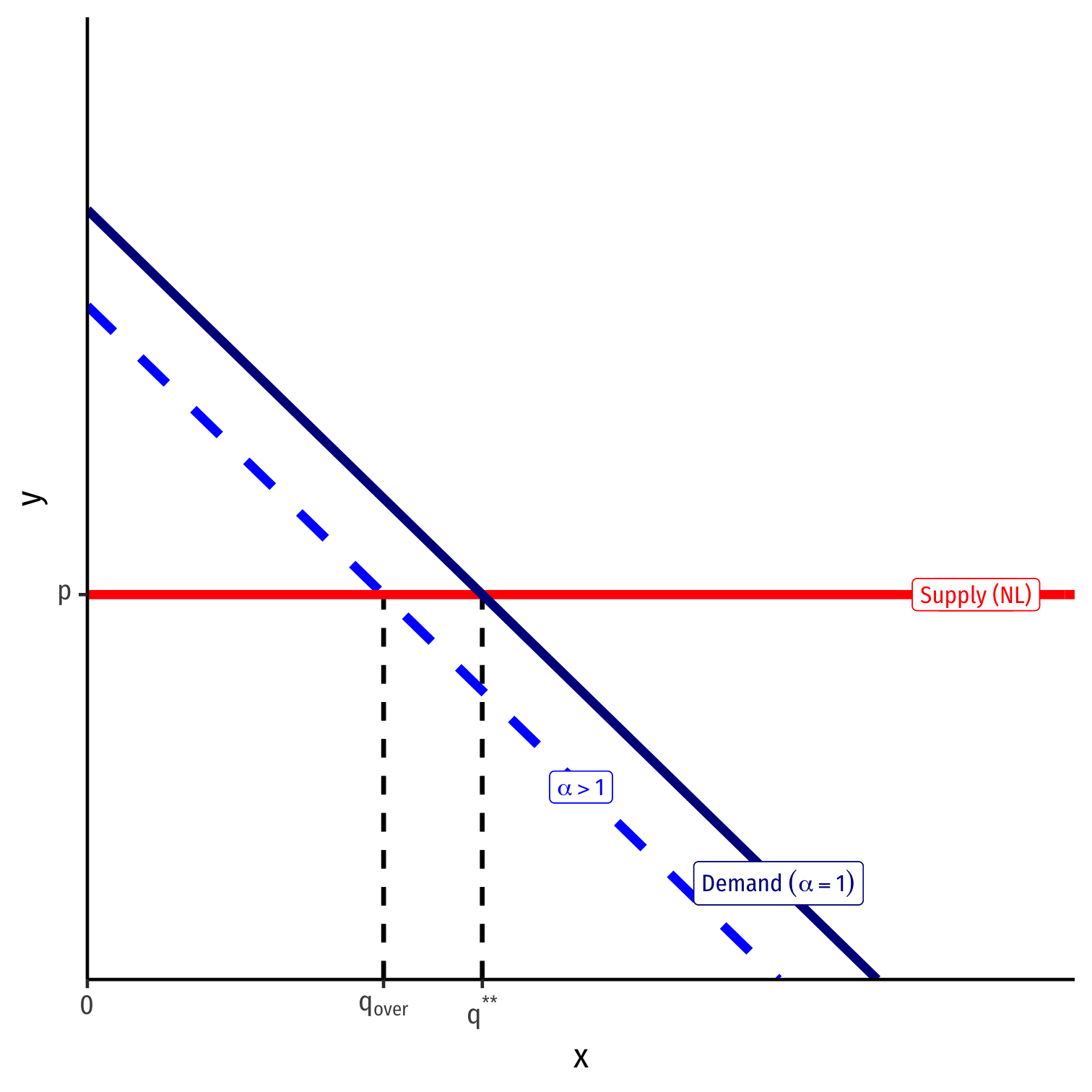

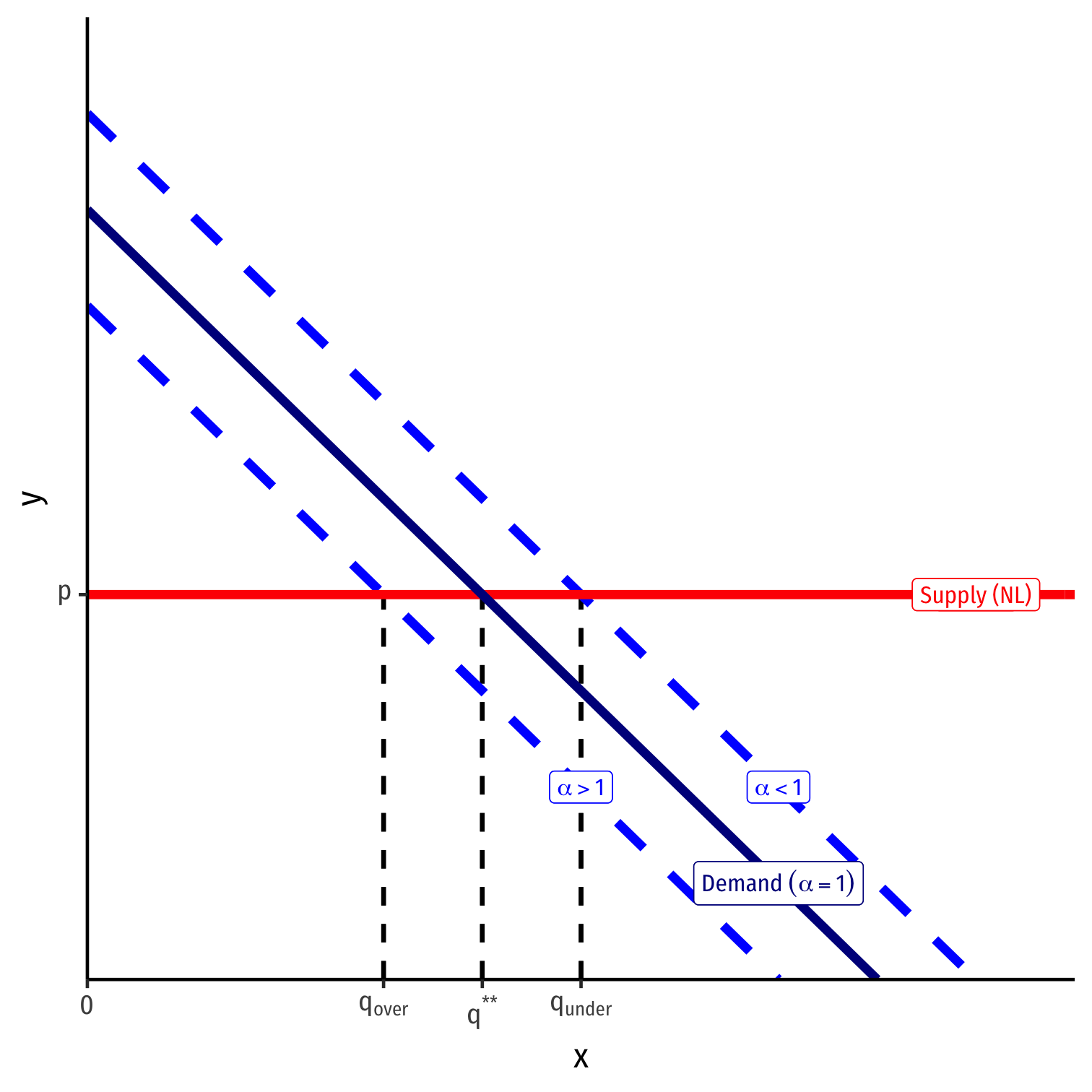

As an example, conside no liability (s=0)

Equilibrium output where: a−b(q)−αpD=c

If α>1, consumers overestimate risk, demand too little output

Consumer Misperceptions of Risk

As an example, conside no liability (s=0)

Equilibrium output where: a−b(q)−αpD=c

If α>1, consumers overestimate risk, demand too little output

If α<1, consumers underestimate risk, demand too much output

Consumer Misperceptions of Risk

Different under strict liability (s=1), we saw equilibrium output is still efficient q⋆⋆

- Efficient for any α (i.e. regardless of consumer’s mistaken beliefs)

Consumer misperceptions of risk have no effect on output

- Manufacturer fully internalizes the expected damages via the higher market price pSL, accurately reflecting the risk

Consumer Misperceptions of Risk

In other words, when consumers misperceive risk, the liability rule matters for efficiency

- Only under strict liability will misperceptions of risk not affect efficient outcome

In general, the party who more accurately perceives the risk should bear the liability

Supports general historical trend of more strict liability for products

Consumer Precaution

- What about the level of precaution?

Consumer Precaution

- What about the level of precaution?

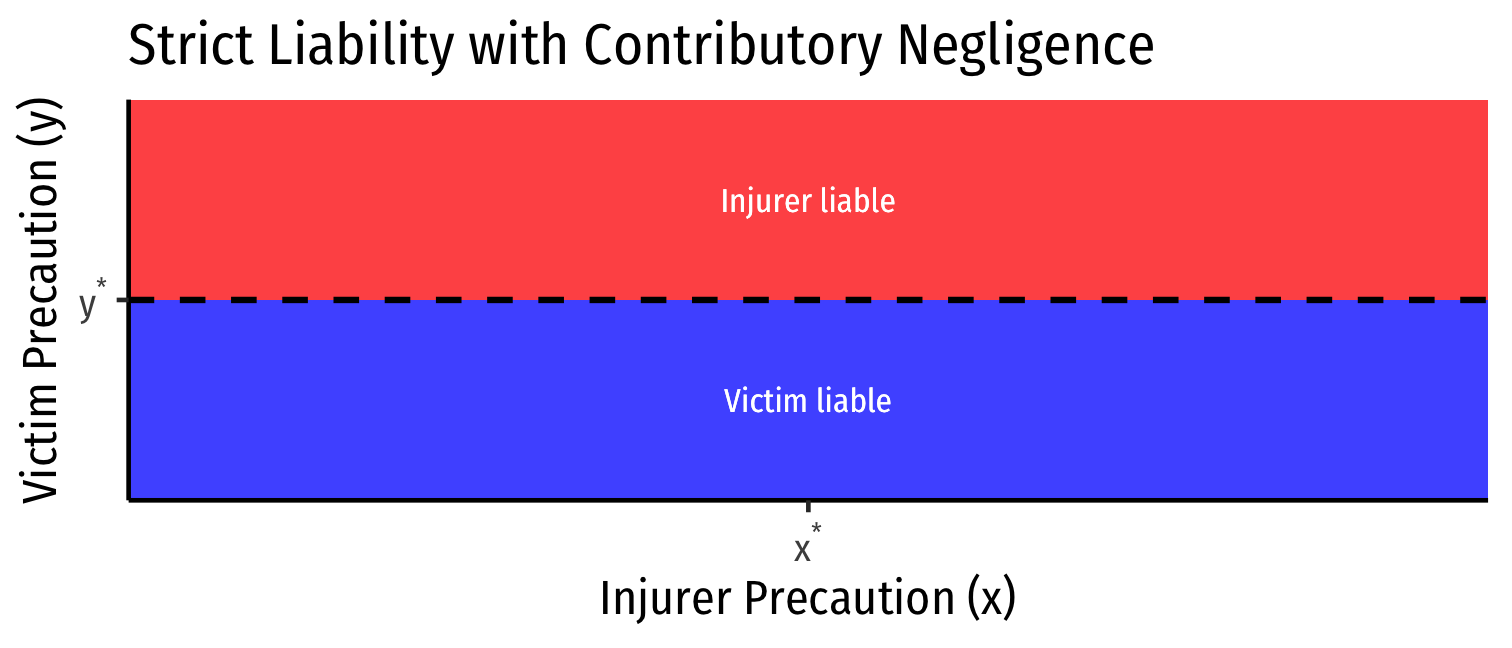

| Rule | Injurer Precaution | Victim Precaution |

|---|---|---|

| No liability | Zero | Efficient |

| Strict liability | Efficient | Zero |

Consumer Precaution

- What about the level of precaution?

| Rule | Injurer Precaution | Victim Precaution |

|---|---|---|

| No liability | Zero | Efficient |

| Strict liability | Efficient | Zero |

- We saw before, under strict liability, Victim has no incentive to take precautions (y=0)

- High cost of enforcing contract conditioned on consumer appropriately using product

Consumer Precaution

- What about the level of precaution?

Consumer Precaution

- What about the level of precaution?

| Rule | Injurer Precaution | Victim Precaution |

|---|---|---|

| No liability | Zero | Efficient |

| Strict liability | Efficient | Zero |

| Strict Liability w/Contributory Negligence | Efficient | Efficient |

Consumer Precaution

- What about the level of precaution?

| Rule | Injurer Precaution | Victim Precaution |

|---|---|---|

| No liability | Zero | Efficient |

| Strict liability | Efficient | Zero |

| Strict Liability w/Contributory Negligence | Efficient | Efficient |

We also saw before that introducing a defense of contributory negligence restores incentive for Victim to take due care to avoid liability

However, most cases do not accept this as a defense!

Conclusions

Contract law is not an adequate remedy for most product related accidents between Producer and Consumer

In theory, Coase Theorem suggests the parties could bargain to fully internalize the accident risk (between pSL and pNL)

But high transaction costs prevent this:

- Consumer misperceptions of product risk

- Inability of producers to monitor consumers carefully using product

High cost of contracting in the presence of these remote risks disproportionate to the benefits of a negotiated level of safety

- Cheaper to use the default rule of having tort law assign safety

Workplace Accidents

Workplace Accidents

What about accidents where workers are injured on the job?

- unsafe working conditions

- negligence by coworkers

Or accidents between workers and strangers/customers in course of employment?

Workplace Accidents

Workers injured on the job are similar to products liability

- An economic relationship between the parties

- Wage adjusts to reflect legal assignment of liability between parties

- Contract law governs these relationships, but may fail in the presence of market failures like above (misperceptions of risk, etc.)

Accidents between worker and stranger are like accidents between strangers

Vicarious Liability and Employment

Vicarious liability: one party is held liable for the harm caused by another

- Parents may be liable for harms their children cause

- Employers may be liable for harms their employees cause

Respondeat superior: “let the master answer”

- Employer is held liable for employee’s torts if employee was acting within the scope of employment

Vicarious Liability and Employment

Respondeat superior gives employers incentives to:

- be more careful who they hire

- be more careful what they assign employees to do

- monitor employees more carefully

Employers are better able to make these decisions (and bear the risks) than employees

Employees are also likely “judgement proof”: unable to pay the full costs of harms

- Employers have “deeper pockets”

Vicarious Liability and Employment

Can implement vicarious liability via:

- Strict liability: employer liable for any harm caused by employee (within scope of employment)

- Negligence: employer liable only if employer was negligent in supervising the employee

Which rule is better? Depends:

- If proving negligent supervision is too difficult, strict liability better

- But negligence gives employer incentives to report employee harms rather than keep quiet (under strict liability)

When Victim is Employee

Historically, employer liability for when employee is the victim was very limited

- Common law duty imposed on employers to maintain a safe workplace and warn of dangers

Employer could avoid liability by demonstrating contributory negligence on part of injured employee

- As we saw before, this leads both parties to take efficient precaution (x⋆,y⋆)

- Wage will adjust to reflect who bears the cost of accident

When Victim is Employee

Historically, “fellow servant rule” shielded employers from liability if the cause of the accident to an employee was the action of another employee

Gives incentive for employees to monitor each other

Perhaps works well for small workplaces where coworkers all frequently interact, but not so well for large businesses

Workers Compensation Laws

In 20th Century, dissatisfaction with common law of workplace accidents led to legislation in all States: workers compensation

Created a form of strict liability for employer

- Employees no longer needed to prove employer negligence to recover damages

- Contributory negligence and fellow servant rules no longer valid defenses

Workers Compensation Laws

However, amount of compensation for workers was fixed by a schedule of damages by injury, and administered by government agencies rather than courts (& lawsuits)

- Often 2/3 of wages

- Employees waive their right to sue employer

“The compensation tradeoff”: employee waives right to sue, but is essentially guaranteed a limited of insurance from injury

Workers Compensation Laws

Benefit to employers: lowers risk of bankruptcy from high damage awards in tort cases

Potential issue in reducing employees incentives for precaution (no defense of contributory negligence), but:

- employers can contract with workers to pay higher wage for greater worker care

- compensation is limited, so reduces employee moral hazard

Workers Compensation Laws

- Another issue: employee must prove the harm was job-related

- Easy for accidents causing physical injury

- Harder for exposure to chemicals that may contribute to cancer decades later...

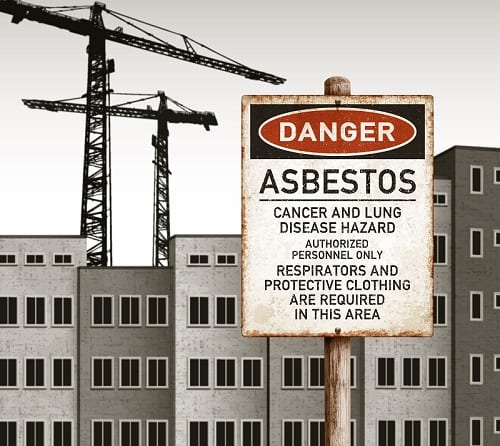

Example: Asbestos

Asbestos is a fibrous material that is an excellent electrical insulator and highly heat resistant, used for decades as a building material

- Probably saved countless lives from preventing fires

But, inhalation of asbestos fibers can lead to serious conditions such as lung cancer, mesothelioma, heart disease

- But this takes 20-30 years to develop

- Believed that about 100,000 people die a year from asbestos exposure-related diseases

Since public health developments in 1970s, asbestos is banned as a building material due to safety hazards

Example: Asbestos

- Like any occupational hazard, risk can be properly internalized via two mechanisms:

1) Compensating differentials in wages

- Wages are higher for employees in dangerous occupations (and give employers an incentive to invest in safety to push down wage premiums)

- Problem: this only works when employees know there are dangers present!

Example: Asbestos

- Like any occupational hazard, risk can be properly internalized via two mechanisms:

2) Workers compensation laws

- Even if employees (and employers) didn’t know about risks (and gives employers incentive to invest in safety to push down insurance premiums)

- Problem: have to show harm was caused by on-job activity!

- Statute of limitations is too short, harm doesn’t develop for 30 years!

Borel v. Fibreboard

Borel v. Fibreboard Paper Products Corporation (1973)

Borel filed personal injury lawsuit against Fibreboard and 9 other asbestos-insulation manufacturers after being diagnosed with mesothelioma

Argued manufacturers should be liable because it asbestos did not come with warning labels

By then, strict liability for manufacturers in products liability

Borel v. Fibreboard

Borel v. Fibreboard Paper Products Corporation (1973)

Sadly, Borel died before the lawsuit was over

Court found these companies were strictly liable, even though Borel was not an employee of Fibreboard

Now, consumers can sue manufacturers directly, without an economic relationship (like employment) — products liability

Joint and Several Liability

Suppose a victim was hurt ($1,000 worth of damages) in an accident caused by multiple injurers

Joint liability: victim can sue all injurers combined (as co-defendants) for $1,000

- Married couple defaulting

Several liability: victim can sue each injurer separately, but each is only liable for the amount they contributed to the accident

Joint and several liability: law treats all injurers as jointly liable, and victim can sue any of them for the full damages

- Injurers' jointly are responsible for sorting out their respective contributions

Joint and Several Liability in Tort Law

Joint and several liability applies when:

- Defendants acted together to cause the harm

- Or harm was indivisible (impossible to tell who was at fault)

Good for the Victim

- No need to prove exactly who caused the harm, or to what degree

- Greater chance of recovering full damages

- Instead of suing Defendant most responsible, sue the one with the greatest ability to pay (“deep pockets”)

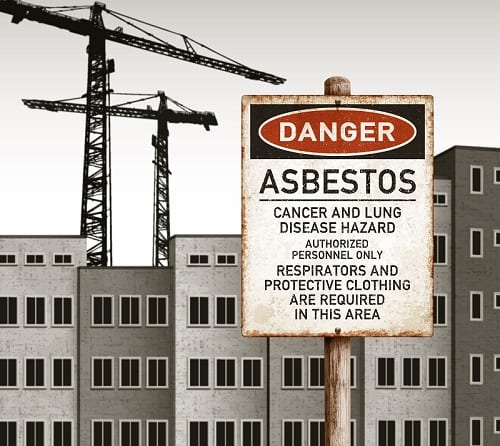

Joint & Several Liability: Asbestos

With joint & several liability for asbestos, the claims are increasing faster than the actual injuries

From Wikipedia):

“Asbestos lawsuits in the U.S. have included the following as defendants: manufacturers of machinery that are alleged to have utilized asbestos-containing parts; owners of premises at which asbestos-containing products were installed; retailers of asbestos-containing products, including hardware, home improvement and automotive parts stores; corporations that allegedly conspired with asbestos manufacturers to deliberately conceal the dangers of asbestos; manufacturers of tools that were used to cut or shape asbestos-containing parts; and manufacturers of respiratory protective equipment that allegedly failed to protect workers from asbestos exposure.”

Joint & Several Liability: Asbestos

The problem is, you’re not suing the least-cost avoider of the harm!

- The lawsuits are not generating incentives for optimal safety or deterrence

An excessive amount of rent-seeking and frivolous claims

- Creates stress on legal system, reducing ability to actually compensate for real harms

Joint & Several Liability: Asbestos

Joint & Several Liability: Asbestos

Asbestos

- From Wikipedia):

Asbestos litigation is the longest, most expensive mass tort in U.S. history, involving more than 8,000 defendants and 700,000 claimants. By the early 1990s, "more than half of the 25 largest asbestos manufacturers in the US, including Amatex, Carey-Canada, Celotex, Eagle-Picher, Forty-Eight Insulations, Manville Corporation, National Gypsum, Standard Insulation, Unarco, and UNR Industries had declared bankruptcy. Analysts have estimated that the total costs of asbestos litigation in the U.S. alone will eventually reach $200 to $275 billion." The amounts and method of allocating compensation have been the source of many court cases, and government attempts at resolution of existing and future cases.