4.1 — Legal Theory of Tort Liability

ECON 315 • Economics of the Law • Spring 2021

Ryan Safner

Assistant Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/lawS21

lawS21.classes.ryansafner.com

A Recap of Our Approach So Far

Recap of Our Approach So Far

Efficiency

- maximize total surplus to all individuals

- scarce resources owned by whoever values them the most

- make changes if social benefit > social cost

Design legal system that obtains efficient outcomes

- Once the rules are set, people only act in own self-interest, without regard for efficiency

- So the goal is to set up the rules so that people acting in their interest will naturally lead to efficient outcomes

Recap of Our Approach So Far

- Coase's insights give us a way to accomplish this:

If transaction costs are low, with well-defined and tradeable property rights, parties can bargain voluntarily to reach the efficient outcome.

So the initial allocation of rights doesn't matter for efficiency

But if transaction costs are high, we may not get the efficient outcome

Recap of Our Approach So Far

Led us to two normative guidelines for designing an efficient legal system:

- Minimize transaction costs to facilitate exchange

- Allocate rights as efficiently as possible

Tradeoff between injunctive relief and damages

Recap of Our Approach So Far

Law of property works well for spot transactions

Law of contracts allow for more complicated non-simultaneous trade

- enables cooperation and credible promises

- encourages efficient disclosure of information

- secures efficient commitment to performance

- secures efficient reliance

- supplies efficient default rules and regulations

- fosters enduring relationships

Recap of Our Approach So Far

So far, we have only examined voluntary exchange and mutual consent

- Parties reach an agreement in advance of transaction (though circumstances might change after the agreement)

Up next: “involuntary exchange”

- Parties who did not have an agreement before their (unfortunate) interaction

- Example: you are bicycling to class, I am texting while driving, and I hit you...

- You did not want to deal with me, I did not want to deal with you, but here we are...

Recap of Our Approach So Far...In Other Words

Property law: situations where transaction costs are low enough to get agreement ahead of time (some exceptions of course!)

Contract law: situations where transaction costs are low enough for us to agree to a contract, but high enough that we might not want to renegotiate the contract later (when something unexpected happens)

Tort law: situations where transaction costs are too high to agree on anything in advance

An Example

Example: I am distracted and hit you with my car while you are bicycling to class

- I did not want or intend to hit you

Put aside questions of justice and retribution...and simply consider incentives

Distracted driving (and hitting people) clearly imposes a serious negative externality on others

Without any laws, we expect more than the efficient amount of distracted driving

Society needs to design law to discourage this behavior

- How do we do this?

An Example

Harder with tort law, because I did not intend to hit you (and we had no prior agreement)

I made a choice ahead of time (to be distracted) that increased the likelihood of an accident

An Example

Harder with tort law, because I did not intend to hit you (and we had no prior agreement)

I made a choice ahead of time (to be distracted) that increased the likelihood of an accident

An Example

Harder with tort law, because I did not intend to hit you (and we had no prior agreement)

I made a choice ahead of time (to be distracted) that increased the likelihood of an accident

So how do we create an incentive to avoid this type of outcome?

Can imagine several ways

An Example

An Example

- Punish the choice (criminal law, regulations): make it illegal to drive distracted (even if you don't hit anyone)

An Example

Punish the choice (criminal law, regulations): make it illegal to drive distracted (even if you don't hit anyone)

Punish the outcome (“Strict liability”): if you hit someone, regardless of the choice you made, (distracted or not), you are liable

An Example

Punish the choice (criminal law, regulations): make it illegal to drive distracted (even if you don't hit anyone)

Punish the outcome (“Strict liability”): if you hit someone, regardless of the choice you made, (distracted or not), you are liable

Punish the combination of choice & outcome (““Negligence”): if you hit someone, and you made a bad choice increasing the probability of an accident, you are liable

Tort Law

Tort: noun. (French): injury

Contract law: where someone harms you by breaking a promise they made

Tort law: where someone harms you without having made any promises

Tort Law vs. Criminal Law

“If someone shoots you, call a cop. If someone hits your car, call a lawyer.”

- Actually a lot of overlap between criminal law & tort law

- Some torts have equivalent crimes

- Intentional vs. unintentional torts

- Can sue a criminal for damages in civil case

- O.J. Simpson example

Torts and Efficiency

As usual, we will focus on attaining efficient outcomes

I hit you with my car, causing $1,000 worth of damage to you (no damage to me)

- Should I have to pay damages?

Torts and Efficiency

Suppose the law holds me liable for:

| Nothing | $1,000 | $50,000 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| You | -1,000 | 0 | 49,000 |

| Me | 0 | -1,000 | -50,000 |

| Joint | -1,000 | -1,000 | -1,000 |

Whatever happens after the accident has no apparent effect on efficiency

- Just redistributing income, each of us obviously has different preference for this

- No new value created or destroyed

...this can't be the way to think about efficiency

Remember the First Day of Class...

Everything that happens after the accident merely affects distribution, not efficiency

Damage is already done, lawsuit = how to clean up the mess:

- assign blame

- maybe punish someone

- maybe compensate

Remember the First Day of Class...

- Before the incident, lots of decisions were made, e.g.

- how much to invest in precaution (how fast to drive, wearing a helmet while biking, etc)

- reaching a contractual agreement

- transforming my property (planting trees that block my neighbor's view)

- relying on my supplier to deliver on time

Remember the First Day of Class...

These were made based on expectations about what will happen

These decisions affect the outcomes and how much value is created and destroyed by society

More importantly, how do laws and court decisions affect future behavior on the margin?

Economists are more forward-looking about law

Designing Efficient Tort Law

How do we structure tort law to get people to behave in a way that results in efficient outcomes?

For deliberate harms: make punishments severe (criminal law)

For accidental harms, much trickier

- The goal is not no accidents, but the efficient amount of accidents!

Designing Efficient Tort Law

How do we structure tort law to get people to behave in a way that results in efficient outcomes?

Unlike property law, no injunctive relief possible

Unlike contract law, no agreement in advance

Cooter and Ulen: essence of tort law is

“the attempt to make injurers internalize the externalities they cause, in situations where transaction costs are too high to do this through property or contract rights”

The Legal Theory of Torts

The Legal Theory of Torts

Plaintiff: person who brings the lawsuit

- Victim, person who is harmed

Defendant: person who is being sued

- Injurer, person who caused the harm

In a tort case, Defendant caused some harm to Plaintiff, who is asking for damages

The Legal Theory of Torts

Like contract law, a well-known legal theory of tort liability developed 100 years ago

A valid tort case (where Plaintiff can collect damages from Defendant) has three elements:

- Harm

- Causation

- Breach of duty (sometimes)

Harm

For a tort to exist, the Plaintiff needs to have suffered some harm

“Without harm, there is no tort”

Examples:

- Gas station sells gas with defective additive to cars with custom carburetors

- Manufacturer exposes workers to a chemical that increases cancer risk by 1%

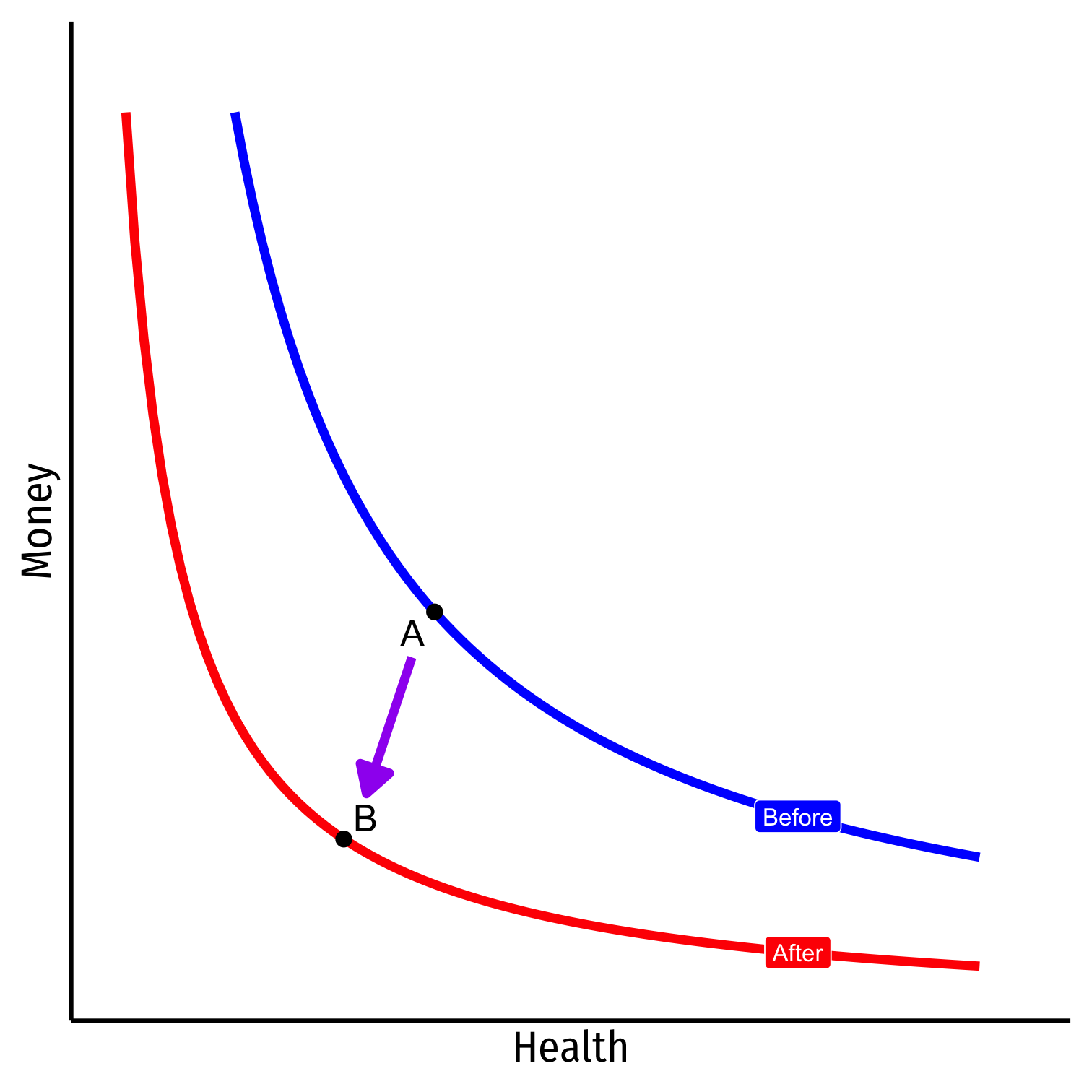

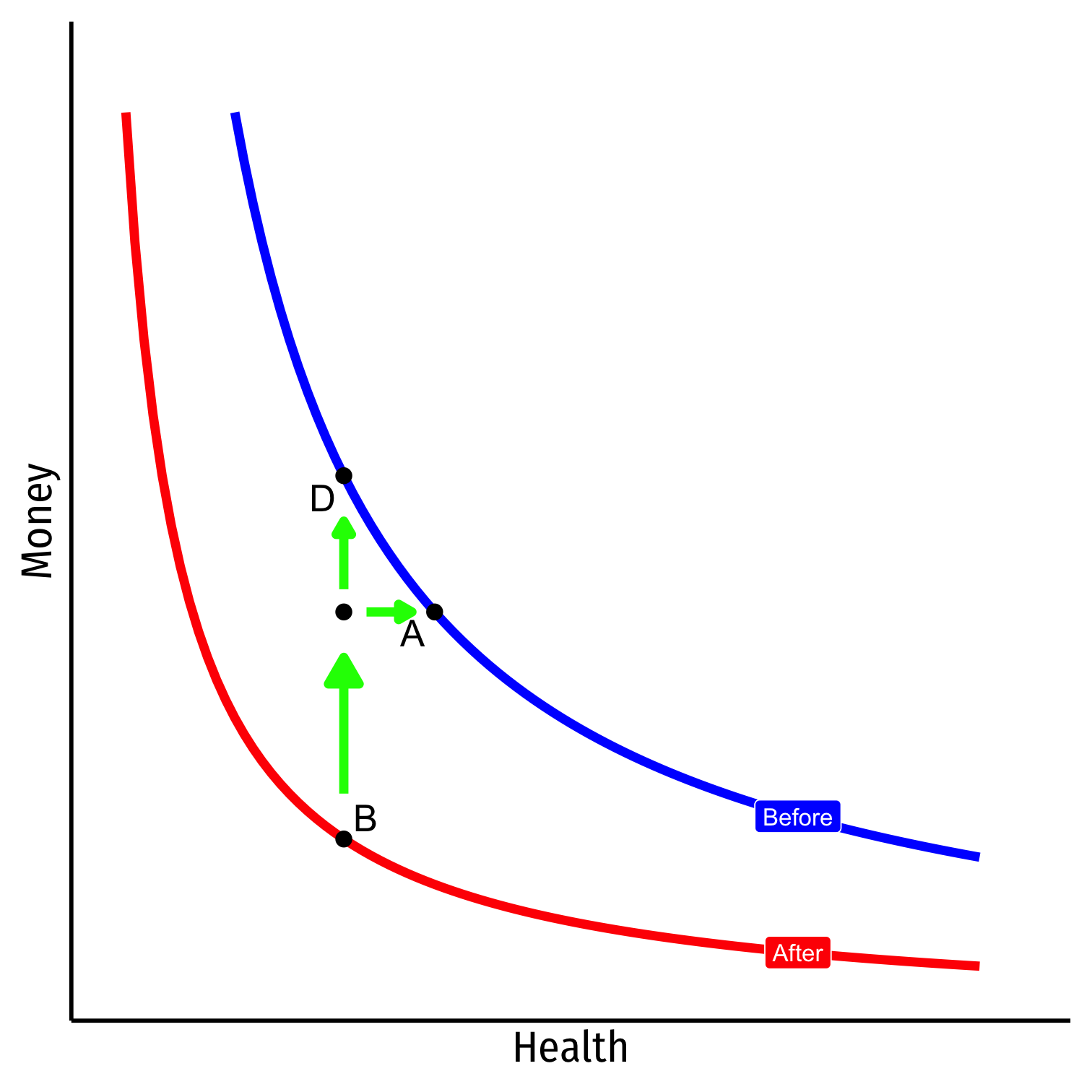

Harm: Perfect Compensation

Consider some preference relationship between money and health

Accident has caused injured party (Plaintiff) to suffer harm

- Model as fall to lower indifference curve

Harm: Perfect Compensation

Consider some preference relationship between money and health

Accident has caused injured party (Plaintiff) to suffer harm

- Model as fall to lower indifference curve

Perfect compensation would restore Plaintiff to original level of well-being

- Return to original indifference curve

- Again, often via money damages

- Sometimes, can't restore health, must find some equivalent amount of of money to compsensate

Harm: Perfect Compensation

Many of the harms are tangible:

- Medical costs

- Lost income

- Damaged property

But there can also be intangible harms:

- Emotional distress

- Pain and suffering

- Loss of companionship

Harm: Perfect Compensation

- In theory, perfect compensation should cover all these harms

- Historically, courts were less willing to compensate for intangible harms (hard to measure)

- Over time, U.S. courts have been compensating more for intangible harms

Harm: Perfect Compensation

Should we compensate for intangible harms?

Pros: the closer liability is to the full harm done, the better the incentive to avoid these harms (internalize the full externality)

Cons: hard to measure, subjective value, high variance in award sizes, incentive to rent-seek?

Causation

Causation: Cause-in-fact

To be liable for a tort, the Plaintiff must show that the Defendant caused them harm

Cause-in-fact test

- “But for the Defendant's actions, would the harm have occurred?”

- A→B

- Ambiguity (recall Coase’s insight that it takes two parties to create harm!)

Causation: Cause-in-fact

David D. Friedman

(1945—)

“I stop my friend in the street to chat. He continues on down the street. As he passes by an office building, a safe falls out the window and crushes him. Have I caused his death? Should I be liable?

One sense of “I caused his death” is “had I not acted as I did, he would not have died”—the “but for” definition of causality. In that sense I killed my friend—if I had not delayed him, he would not have been under the safe when it fell. Yet it would seem odd to blame me and odder still to hold me liable. Why?” (p.191)

Causation: Cause-in-fact

- What about setting in motion a long chain of events that leads to harm?

- A→c→d→e→B

- Event A satisfies the “but-for” test!

Causation: Palsgraf v. LIRR

Palsgraf v. Long Island Rairoad Co., 248 N.Y. 339 (1928)

Railroad attendant’s actions caused, but were not the proximate cause to Ms. Palgraf's injuries

Court ruled attendant’s actions were too remote to be considered a proximate cause

Causation: Palsgraf v. LIRR

“Plaintiff [Mrs. Palsgraf] was standing on a platform of defendant’s railroad after buying a ticket to go to Rockaway Beach. A train stopped at the station, bound for another place. Two men ran forward to catch it. One of the men reached the platform of the car without mishap, though the train was already moving. The other man, carrying a pack- age, jumped aboard the car, but seemed unsteady as if about to fall. A guard on the car, who had held the door open, reached forward to help him in, and another guard on the platform pushed him from behind. In this act, the package was dislodged, and fell upon the rails. It was a package of small size, about fifteen inches long, and was covered by a newspaper. In fact it contained fireworks, but there was nothing in its appearance to give notice of its contents. The fireworks when they fell exploded. The shock of the ex- plosion threw down some scales at the other end of the platform many feet away. The scales struck the plaintiff, causing injuries for which she sues.”

Source: Court Opinion

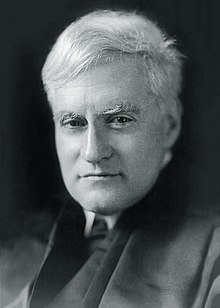

Causation: Palsgraf v. LIRR

Benjamin N. Cardozo

1870—1938

Associate Justice of U.S. Supreme Court

“Negligence, like risk, is thus a term of relation. Negligence in the abstract, apart from things related, is surely not a tort, if indeed it is understandable at all...Negligence is not a tort unless it results in the commission of a wrong, and the commission of a wrong imports the violation of a right, in this case, we are told, the right to be protected against interference with one's bodily security.”

“[T]he conduct of the defendant's guard, if a wrong in its relation to the holder of the package, was not a wrong in its relation to the plaintiff, standing far away. Relative to her it was not negligence at all...proof of negligence in the air, so to speak, will not do...a different conclusion will involve us, and swiftly too, in a maze of contradictions.”

Source: Court Opinion

Causation: Proximate Cause

Proximate cause: defendant's actions must not be too distant from the event that caused the actual harm to Plaintiff

But no precise legal definition of how close “proximate” is

- In general, whatever consequences are “reasonably foreseeable” from Defendant's actions

Breach of Duty

Breach of Duty

Breach of duty is sometimes, but not always necessary for a tort to exist

Depends on the liability rule in place!

Consider two different tort liability rules: strict liability and negligence

| Strict Liability | Negligence |

|---|---|

Breach of Duty

- Under strict liability, only necessary for Plaintiff to show Defendant caused them harm

- Does not matter whether Defendant was cautious or at fault!

- Tends to be used for inherently dangerous activities (blasting with dynamite, etc.)

| Strict Liability | Negligence |

|---|---|

| 1. Harm | |

| 2. Causation | |

Breach of Duty

- Under a (more common) negligence rule, Plaintiff must show that Defendant breached a legal duty owed to Plaintiff, and this led to the harm

- Injurers owe victims the legal duty of “due care”

- When an Defendant/injurer breaches their legal duty, they are “at fault”, or found “negligent”

- If Defendant demonstrates they exercised due care, they are not liable for any harms to Plaintiff

| Strict Liability | Negligence |

|---|---|

| 1. Harm | 1. Harm |

| 2. Causation | 2. Causation |

| 3. Breach of duty (fault) |

Negligence and Due Care

So under a negligence rule:

If I breach by due of due care and injure you, I am liable

If I exercise the appropriate level of care but still injure you, I am not liable

How is the standard of care determined?

- How careful does Injurer have to be to avoid liability?

- Is it negligent to drive 45 in a 40 MPH zone? 41?

Determining the Standard of Care

In some settings, governments impose safety regulations used as the standard for negligence

- Speed limits for highway driving

- Requirements that bicycles have breaks

- Requirements that lifeguards must be on duty

- Workplace regulations

Some standards are left vauge

- “Reckless driving” may depend on road and weather conditions

- Common law focuses on duty of “reasonable care”: the level of care a reasonable person would have taken

Reasonable Care Standard

Reasonable Care Standard

Strict Liability vs. Negligence Rule

Strict liability rule: Plaintiff must prove harm and causation

Negligence rule: Plaintiff must prove harm, causationn, and negligence

Historical development

- In early Europe, strict liability was typical rule

- By early 1900s, negligence became typical rule

- Second half of 1900s, strict liability became more common again, especially for products liability in U.S.