3.3 — Invalidating Contracts

ECON 315 • Economics of the Law • Spring 2021

Ryan Safner

Assistant Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/lawS21

lawS21.classes.ryansafner.com

When Should a Contract Not be Enforced?

When Should Voluntary Trade Be Prohibited?

Recalling in property law:

- Coase theorem: to get efficient outcomes, let people trade whenever they want to

- But also exceptions: unalienability rules, e.g. selling uranium to a terrorist

Similarly with contract law:

- To get efficient outcomes, generally enforce any contract both parties want enforced

- But also exceptions: contracts that should not be enforced

When Should Voluntary Trade Be Prohibited?

Situations where promise will not be enforced and no compensation is due

Two categories of conditions:

Formation defenses

- claim that valid contract does not exist

- example: no consideration

Performance excuses

- Yes, a valid contract exists

- but circumstances have changed and promisor should be allowed to breach without penalty

When Should Voluntary Trade Be Prohibited?

- Most legal doctrines for invalidating a contract have two economic bases:

- individuals’ agreement was not rational

- high transaction costs or a market failure

- information, externalities, monopoly, etc.

Ideal Contract Conditions & Ideal Market Conditions

Main goal of contract is facilitating gains from trade for efficiency

Economic theory teaches us that competitive markets maximize gains from trade (and efficiency) when:

- Individuals are rational

- No externalities

- No market power/disproportionate bargaining power

- Perfect information

- Low transaction costs

Violations of these conditions often imply a market failure

- analogously, might imply a contract should be invalid

Obvious Cases: Contracts that Break the Law

Contract that violates the law is unenforceable

- Examples: buying a kilo of cocaine for $25,000; murder-for-hire

Less obvious: contracts that derogate public policy are also unenforceable

- Examples: victim of a crime rewarding police for catching criminal; contracts in restraint of trade (antitrust law)

Recall inalienability rules; enforcing these contracts creates negative externalities

Party that reasonably knew performance was illegal should be liable

Incompetence

Incompetence

Courts will not enforce contracts with people with mental incapacity (lack of rationality) — incapable of understanding the implications of a contract

- Children

- Legally insane

- Intoxicated?

Doctrine of incompetence: one party “not competent to enter into the agreement”

- Offer and acceptance not valid, no “meeting of the minds”

Incompetence

“The kid bid about $113,000 on the aircraft at a fixed price...The kid’s dad notified the seller that his son had hit the buy now button and lacked the money in his piggy bank to cover the jet.”

Incompetence

What about if you signed a contract while drunk?

Need to be really really really drunk to get out a contract

“Intoxicated to the extent of being unable to comprehend the nature and consequences of the instrument he executed.”

Incompetence: Lucy v. Zehmer

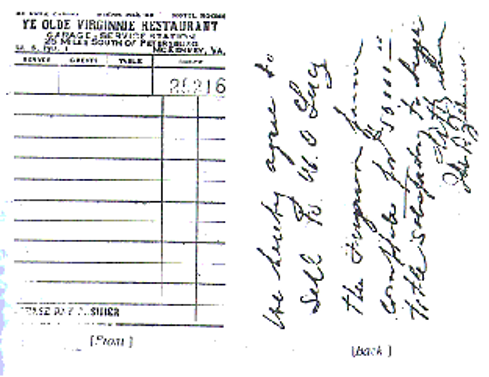

Lucy v. Zehmer Virginia Sup Ct 1954

Zehmer owned a farm (“the Ferguson farm”), Lucy had been trying to buy it for some time

While out drinking, Lucy “already high as a Georgia pine” offers $50,000

- Zehmer responds: “You haven’t got $50,000 in cash”

- ...eventually, Lucy grabs a discarded guest check and writes:

“We hereby agree to sell W.O. Lucy the Ferguson Farm complete for $50,000.00, title satisfactory to buyer.”

Incompetence: Lucy v. Zehmer

A day later, Lucy raises money to carry out the contract

Zehmer later claims he was drunk and joking: “a bunch of two doggoned drunks bluffing to see who could talk the biggest and say the most”

Lucy sues for specific performance: court issuing an order for the contract to be performed as specified (i.e. Zehmer sell to Lucy for $50,000)

Incompetence: Lucy v. Zehmer

Lucy v. Zehmer 196 Va. 493; 84 S.E.2d 516 (1954)

Court: Zehmer not so drunk as to be “unable to comprehend the nature and consequences” of what he was doing

Joke or not, Zehmer behaved exactly as if he actually wanted to sell, wrote what looked like a proper (if unorthodox) contract

- It's not Lucy’s duty to know Zehmer was joking!

Court held the contract was valid and Zehmer owed specific performance

Incompetence: Should Drunkenness Count?

Might think Zehmer, being drunk, lacked necessary intent to enter into a contract

Makes more sense to not easily invalidate a contract just for drunkenness/joking

- Otherwise, rent-seeking & excessive litigation over how drunk someone was, more signing of contracts at bars, etc.

If you are visibly drunk and other party clearly knows, court might be more willing to invalidate (on some other grounds coming soon)

Moral of the story: don’t get drunk with people who might ask you to sign a contract!

Similarly, the Borat Lawsuits

“Two college fraternity buddies shown guzzling alcohol and making racist remarks in the “Borat” movie have lost their bid for a court order to cut the scene they claim has tarnished their reputations...The students sued the movie’s distributor and producers last month, saying filmmakers had duped them into appearing in “Borat” by getting them drunk and falsely promising the film would never be shown in the United States.”

“The scene at issue in the lawsuit depicts Borat getting drunk with three frat boys in a motor home while they watch a sex tape and make racist remarks about slavery and minorities in the United States.”

Source: Reuters (Jan 20, 2007)

See also this great legal analysis of this case, has to do with the validity of “merger clauses” in contracts

Duress

Dire Constraints

Court will not enforce contracts made under dire constraints, e.g.:

Necessity

- Example: I'm about to starve, someone offers me a sandwich for $10,000; my boat is about to sink, someone offers to save me for $1 million

- Contracts would be held invalid, I signed out of necessity (my BATNA is death)

Dire Constraints

Court will not enforce contracts made under dire constraints, e.g.:

Duress

- The other party is responsible for the situation I am in

- “I made him an offer he couldn’t refuse”

- Contract signed at gunpoint would not be enforced by courts

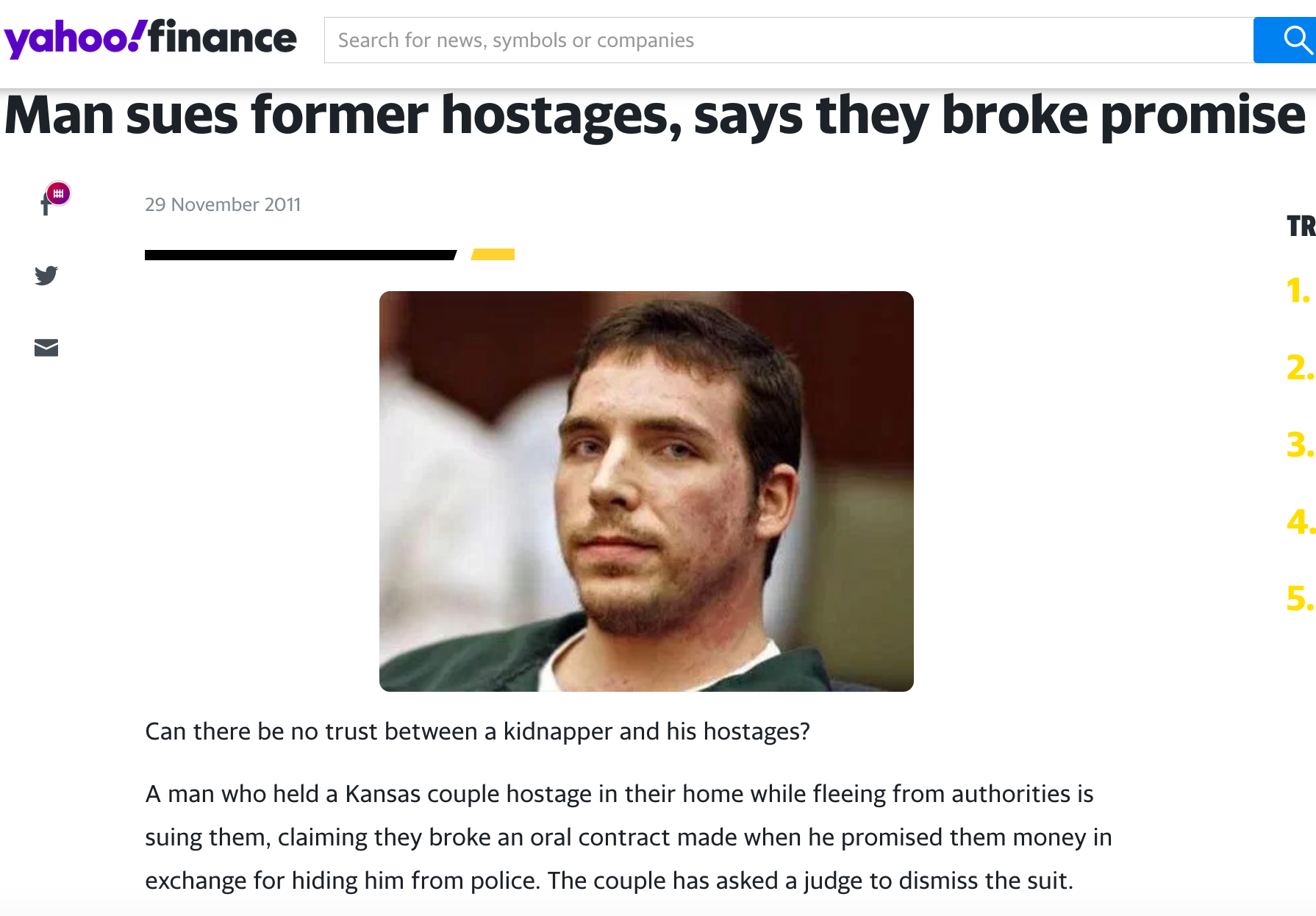

Duress

“A man who held a Kansas couple hostage in their home while fleeing from authorities is suing them, claiming they broke an oral contract made when he promised them money in exchange for hiding him from police. The couple has asked a judge to dismiss the suit...Jesse Dimmick of suburban Denver is serving an 11-year sentence after bursting into Jared and Lindsay Rowley's Topeka-area home in September 2009...Dimmick filed a breach of contract suit in Shawnee County District Court.”

“‘I, the defendant, asked the Rowleys to hide me because I feared for my life. I offered the Rowleys an unspecified amount of money which they agreed upon, therefore forging a legally binding oral contract,’ Dimmick said in his hand-written court documents. He wants $235,000, in part to pay for the hospital bills that resulted from him being shot by police when they arrested him.”

Source: Yahoo Finance (Nov 29, 2011)

Friedman on Duress and Rent-Seeking

David D. Friedman

(1945—)

“A mugger catches you alone in a dark alley and offers you a choice: Give him a hundred dollars or he kills you. You reply that your life is well worth the price, but unfortunately you are not carrying that much cash. He offers to take a check. When you get home, should you be free to stop payment? Should a contract made under duress be enforceable?” (p.152)

Friedman on Duress and Rent-Seeking

David D. Friedman

(1945—)

“The argument in favor of enforceability is that if the contract is not enforceable, the mugger will refuse your check—or accept it and then make sure you can’t stop payment by killing you and cashing the check before news of your death reaches the bank. Seen from that perspective, it looks as though even a contract made under duress produces benefits for both parties and so should be enforceable. You prefer paying a hundred dollars to being killed, he prefers receiving a hundred dollars to killing you. Where’s the problem?

Friedman on Duress and Rent-Seeking

David D. Friedman

(1945—)

“The problem is that making the contract enforceable makes offering people the choice between their money and their life a much more profitable business—most of us have more in our checking accounts than in our wallets. The gain from enforceability is a better chance, if you are mugged, to buy yourself free. It must be balanced against the higher probability of being mugged. It seems likely that the current legal rule, holding contracts made under duress unenforceable, is the efficient one.”

Duress and Rent-Seeking

Recall Efficiency requires enforcing a contract if both parties wanted it to be enforceable

- Mugger did – he wants your $100

- You did – you’d rather pay $100 than be killed

So why not enforce it?

- Makes muggings more profitable, leads to more muggings

Tradeoff: refuse to enforce a Pareto-improving trade in order to avoid incentive for bad behavior

Peace Treaties?

Tradeoff means not always optimal to rule out enforceability under duress!

Example: what about peace treaties between nations at war?

- Contract signed under duress: losing side facing threat of continuing to battle a superior force

Most people agree peace treaties being enforceable is a good thing

- Ex post, make war less costly, end it quicker

- But might this encourage more wars?

Likely efficient for peace treaties to be enforceable but promises made a mugger to not be!

Real Duress vs. Fake Duress

Courts won’t enforce contracts made under threat of harm

- “Give me $100 or I'll shoot you”

But many negotiations contain threats

- “Give me a raise or I'll quit”

- “$3,000 is my final offer, take it or I'll walk”

- This is fine, often necessary to tease out both parties’ BATNAs and determine whether it’s efficient to cooperate

Real Duress vs. Fake Duress

- What’s the difference? Consider what happens in each case when bargaining fails

- First case: threat to destroy value

- Second case: failure to create value

Real Duress vs. Fake Duress

More subtle in cases involving contract modification: changes to contract made between formation & performance

“Preexisting duty” rule: law only recognizes changes to contract supported by new consideration

- Ordinarily, self-enforcing rule

- Example: hardware store requests more snow shovels from supplier during unexpectedly harsh winter; supplier will provide them for more payment; (essentially a new contract where both benefit)

What if events cause a party to agree to a modification that she later regrets? Coerced?

Real vs. Fake Duress: Alaska Packers

Alaska Packers’ Association v Domenico (117 F. 99, 9th Cir. 1902)

APA hired sailors to go fishing for salmon off coast of Alaska

- Crew agreed to wage before setting sail

Once at sea, sailors refused to work unless their wage was increased

- Ship captain, in no position to refuse, complied with their demands

- later refused to pay, sailors sued the company

Real vs. Fake Duress: Alaska Packers

Alaska Packers’ Association v Domenico (117 F. 99, 9th Cir. 1902)

Court voided the new contract on grounds that there was no additional consideration to support the promised wage increase

- All the crew offered in return was to complete the job they were initially hired for at wage they agreed to

Want to avoid monopoly power and one-sided bargaining power

- exploiting other side’s poor BATNA because you put them in that position

Real vs. Fake Duress: Goebel v. Linn

Goebel v. Linn (47 Mich. 489, 11 N.W. 284, 1882)

Brewery contracted with ice company to supply ice during the summer

Unusually warm winter caused ice shortage

- Ice company requested a price increase, brewery (having already brewed beer that would spoil) agreed

Brewery later reneged on paying the higher price

- Claimed it was unenforceable because ice company had offered no new consideration (merely performed original promise)

Real vs. Fake Duress: Goebel v. Linn

Goebel v. Linn (47 Mich. 489, 11 N.W. 284, 1882)

Seems like straightforward application of preexisting duty rule (?)

Court enforced the modification in this case!

- Reasoned the price increase was necessary to sustain the ice company in the face of genuine economic changes

Real vs. Fake Duress: Monopoly Power

These cases show “economic duress” is really about preventing monopoly power

Alaska Packers case was pure opportunism, no genuine economic changes

Goebel case was a genuine economic change (supply curve shifted upward)

- Enforcing the contract resulting from true cost increases enhances the value of the contract

- promotes beneficial trades that would have been lost otherwise (DWL)

Real vs. Fake Duress: Monopoly Power

Recall: under bargain theory, courts will enforce any legitimate bargain, not inquire whether the terms are fair

- Historically, weak protection in common law against monopoly

Primarily rely on statutes to reduce monopoly power

- Antitrust laws, regulation of business

Unconscionability

But there is a growing body of precedent in common law banning contracts that are unconscionable

- terms appear to be grossly unfair to one of the parties

- terms which would “shock the conscience of the court”

Logic: party would not have voluntarily accepted such terms, must have been either incompetent, under duress, or defrauded

- but there is no evidence of any of these (to constitute reasons to invalidate contract)

Court shifts burden to defendant to prove that contract was fair when it was agreed to

Unconscionability

Williams v. Walker-Thomas Furniture Co. (350 F.2d 445, D.C. Cir. 1965)

WT Co. extended credit to Williams to buy several pieces of furniture over 1957-1962

- Contract contained “add-on” clause where none of the furniture could be considered paid off until all pieces were paid off

- If Williams defaulted on any item, company could repossess all furniture items, including those apparently paid off

Court ruled the clause unconscionable, grossly unfair to low-income buyers (form of economic duress)

Unconscionability

“[W]e hold that where the element of unconscionability is present at the time a contract is made, the contract should not be enforced....Unconscionability has generally been recognized to include an absence of meaningful choice on the part of one of the parties together with contract terms which are unreasonably favorable to the other party....In many cases the meaningfulness of the choice is negated by a gross inequality of bargaining power.”

Williams v. Walker-Thomas Furniture Co. (350 F.2d 445, D.C. Cir. 1965)

Unconscionability

But is this efficient?

- Was the add-on clause the cause, or the response to a market failure?

A tradeoff:

- Firms often not willing to lend to low-income buyers without collateral (the paid-off furniture) to secure the loans

- If contracts like this are invalid, low-income buyers might not be able to buy at all

Unconscionability

Of course consumers can be taken advantage of by complex contracts

Ideally, evidence of incompetence, duress, or fraud should be external to the contract itself

Unconscionability

Unconscionability tends not to be invoked in usual circumstances of monopoly, but in “situational monopoly”

- particular circumstances that limit one’s choice of trading partners

Recall Ploof v. Putnam (boat in storm) from property law

- Putnam was the only person who could give Ploof safe harbor during the storm

- Putnam became monopolist in this situation, where he normally would not have been

Performance Excuses: Impossibility

Impossibility

Next, a performance excuse, impossibility: circumstances change to make performance of the contract impossible

Should the promisor be excused from performing (without penalty)?

A perfect contract would specify who bears each risk, or industry custom might be clear, but occasionally court must fill in gap

Impossibility

- In most situations, where contract & industry norm is silent, promisor usually held liable for breach (pay damages), even when it isn’t their fault

- Analogous to strict liability in tort law

- Example: construction company finishes a building later than promised due to unforseen complications — generally held liable

Impossibility

Sometimes excused by physical impossibility

Examples:

- famous artist agrees to paint someone’s portrait, later dies

- manufacturer whose factory burns down

- civilian ships commandeered for military use

Common legal doctrine to excuse due to a change that “destroyed a basic assumption on which the contract was made”

- painter assumed he’d be alive; manufacturer assumed factory operational; shipper assumed peacetime

Impossibility

What would be efficient? Assign liability to the party who can bear the risk at the lowest cost

In many cases, parties can invest in precautions to minimize these risks of breach

- painter can prioritize commissioned works; manufacturer can install sprinklers in factory

Similar to our findings about gaps, risk from gap should be borne by party that can minimize risk cheapest

- What the contract would have stipulated, had parties bothered to address it

Who Is the Efficient Bearer of Risk?

- A few economic bases to answer this question:

Spreading losses across many transactions

Moral hazard: who is in a better position to influence the outcome?

Adverse selection: who is more aware of the risk, even if they can’t do anything about it?

Who Is the Efficient Bearer of Risk?

David D. Friedman

(1945—)

- Spreading losses:

“Suppose I am having a house built by a large firm that builds many houses each year. There is some risk that the house might burn down while it is being built. We could allocate that risk either to me, by specifying that I will have to pay for the additional construction costs in such a case, or to the builder. Since the builder is building many houses in different places, he can spread the risk; I cannot. From that standpoint at least, our contract should specify a fixed price, whether or not something goes wrong. If the contract does not specify who bears the risk, risk spreading provides an argument for assigning it to the builder” (p.161).

Who Is the Efficient Bearer of Risk?

David D. Friedman

(1945—)

- Moral hazard & influencing the outcome:

“In the case of a firm that builds houses the two arguments go in the same direction. The builder is not only in a better position than I am to spread the risk, he is also in a better position than I am to keep the house from burning down while he is building it” (p.161).

Who Is the Efficient Bearer of Risk?

David D. Friedman

(1945—)

- Adverse selection & awareness of the risk:

“I have agreed to deliver ten thousand customized widgets to you by January 10th. Early on the morning of January 1st a drunk driver smashes his car through the wall of my warehouse, crushing half the widgets. One result is that I will have to replace them, at a cost of a hundred thousand dollars. A second is that I will deliver them a month late, costing you another hundred thousand dollars in lost sales. The drunk driver is dead, and his estate bankrupt. Who pays for the losses?” (p.161).

Who Is the Efficient Bearer of Risk?

David D. Friedman

(1945—)

- Adverse selection & awareness of the risk:

“I did not know that that particular drunk driver was going to crash through that particular wall. But I probably do know a good deal more than you do about the chance that something — accident, strike, or bad planning — will prevent me from delivering the widgets to you on schedule.

“If our contract makes me liable for the resulting loss, you don’t have to worry about that risk in deciding whom to buy your widgets from. You know what price I am charging, and you know that I am insuring you against the risk of nondelivery. If the contract specified that you had to bear the risk, you would need to know the reliability of alternative sellers as well as their price in order to decide which one is offering the best deal,” (p.162).

Who Is the Efficient Bearer of Risk?

David D. Friedman

(1945—)

“As this example suggests, moral hazard and adverse selection tend to cut in the same direction. As a general rule the party with control over some part of the production process is in a better position both to prevent losses and to predict them. It follows that an efficient contract will usually assign the loss associated with something going wrong to the party with control over that particular something,” (p.162).

Who Is the Efficient Bearer of Risk?

That’s why Hadley v. Baxendale rule was so “surprising”

- Baxendale (shipper) could influence speed of delivery, Hadley (miller) could not

- Baxendale was the efficient bearer of delay risk

But court ruled Baxendale was not liable for Hadley’s lost profits, forcing Hadley to bear most of the delay risk/loss

- This only makes sense as a penalty default (Ayres and Gertner)

- Creates incentive for Hadley/millers to reveal urgency of the shipment

Who Is the Efficient Bearer of Risk?

David D. Friedman

(1945—)

“A professional photographer spends six months taking photographs in the Himalayas for National Geographic, at a cost of a hundred thousand dollars. When he gets home, he gives his film to the local Walgreen’s — which loses it. Do they owe him a hundred thousand dollars?

“From the standpoint of risk spreading the answer would be ‘yes.’ Walgreen’s handles a large number of rolls of films each year, so it can easily pool the risk. From the standpoint of moral hazard, incentives to keep the loss from happening, the answer is ‘no,’” (p.161).

Who Is the Efficient Bearer of Risk?

David D. Friedman

(1945—)

“Walgreen’s has no way of knowing that there is anything special about these rolls of film. The only way they can prevent the loss is by increased precautions on all rolls. They have the choice of an inefficiently low level of care for ten rolls of film or an inefficiently high level for ten million. The photographer does know that these films are especially valuable and can avoid the problem by taking them to a specialist film lab and making sure the proprietor realizes what they are. The efficient rule from the standpoint of moral hazard is to make the photographer liable, because he is the one in the best position to prevent the loss. That, called the rule of Hadley v. Baxendale after an early case, is in fact the law.” ” (p.162).

Mistake and Information

Faulty Information

What if the parties made a contract based on a mistake

Four major legal doctrines for invalidating a contract based on faulty information

- fraud

- failure to disclose (sometimes)

- frustration of purpose

- mutual mistake

Fraud

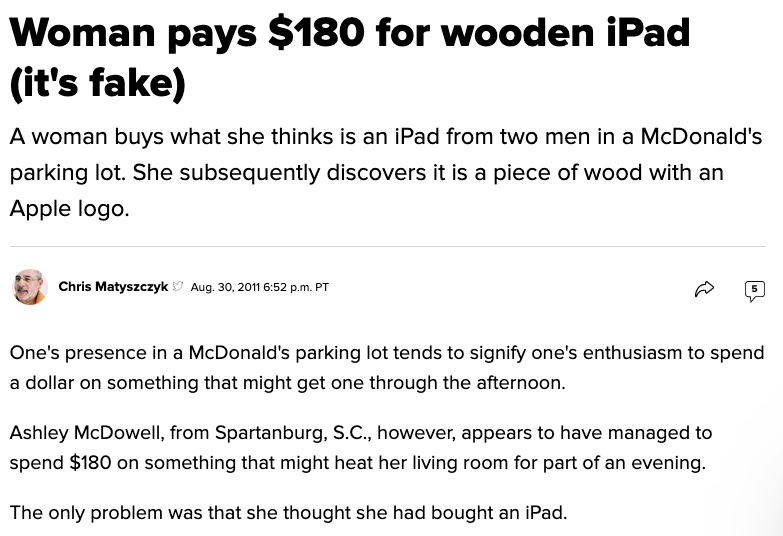

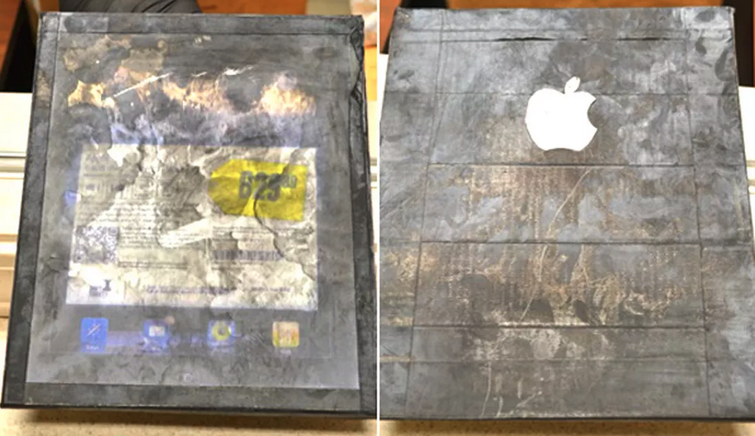

Fraud: one party deliberately tricked the other

Economic rationale for not enforcing contracts with fraud is obvious

- Not a Pareto-improving exchange

Also carries criminal sanctions — the State (as a third party) has an interest in deterring and punishing fraud

Witholding Information

What if you trick someone by witholding information?

In civil law systems, a duty to disclose

- If you fail to provide info you should have, contract voided under failure to disclose

In common law, less so

- Seller obligated to share info about hidden dangers

- but generally not info that makes product less valuable

- Except new products come with an “implied warranty of fitness” for their stated purpose

Withholding Information, Exceptions

Obde v. Schlemeyer (Sup. Ct. WA 1960)

Seller knew building was infested with termites, did not tell buyer

- Termites should have been exterminated immediately to prevent further damage

- Buyer sued seller for damages

Court imposed duty to disclose onto the contract, i.e. awarded damages to buyer

Withholding Information, Exceptions

- Many States require:

- used car dealers to reveal major repairs done

- sellers of homes to reveal certain defects

- lenders to disclose APRs on all loans

- Improve information exchange, lower transaction costs

Mutual Mistake

Fraud & failure to disclose are situations where one party is misinformed

What if both parties are misinformed?

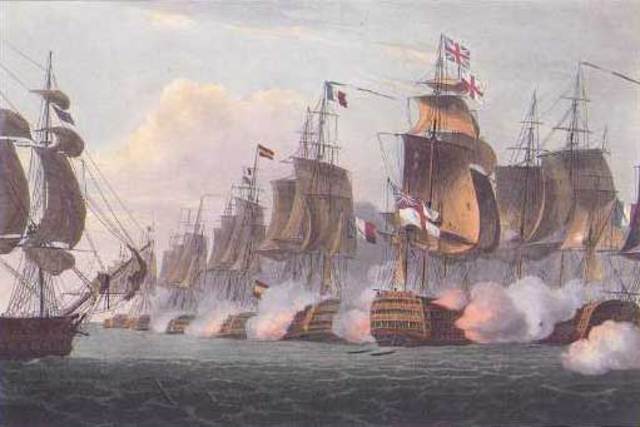

Frustration of purpose: change in circumstances make performance of a promise pointless, court will often not enforce the contract

- Coronation cases (e.g. Krell v. Henry) in 1902 for King Edward VII’s coronation

Coronation parade for King Edward VII, 1902

Mutual Mistake: Frustration of Purpose

When a contingency makes performance pointless, assign liability to party who can bear risk at least cost

- property owners could eliminate the losses by renting again during the rescheduled event

Similar to efficient rule above

Coronation parade for King Edward VII, 1902

Mutual Mistake: About Facts

Mutual mistake about facts: circumstances changed without either party realizing

Examples:

- Logger buys land with timber on it, but unbeknownst to us, a forest fire wiped out all trees before contract signed

- I buy painting at auction, gallery and I later learn the painting was a forgery

Owner at time of event (fire) usually the low-cost avoider of the risk, allocate risk to them by invalidating contract

Mutual Mistake: About Identity

- Mutual mistake about identity: we disagree about what is being exchanged

“One neighbor offers to sell a used car to another for $1000. The buyer gives the money to the seller, and the seller gives the car keys to the buyer. To her great surprise, the buyer discovers that the keys fit the rusting Chevrolet in the back yard, not the shiny Cadillac in the driveway. The seller is equally surprised to learn that the buyer expected the Cadillac. The buyer asks the court to order the seller to turn over the Cadillac.”

Mutual Mistake: About Identity

- Mutual mistake about identity: we disagree about what is being exchanged

“One neighbor offers to sell a used car to another for $1000. The buyer gives the money to the seller, and the seller gives the car keys to the buyer. To her great surprise, the buyer discovers that the keys fit the rusting Chevrolet in the back yard, not the shiny Cadillac in the driveway. The seller is equally surprised to learn that the buyer expected the Cadillac. The buyer asks the court to order the seller to turn over the Cadillac.”

- Court typically invalidates contract based on mutual mistake

- No true meeting of the minds

Knowledge and Control

Efficiency generally requires uniting knowledge and control

Contracts that unite knowledge & control are generally efficient, should be enforced

Contracts that separate knowledge from control may be inefficient, should more often be invalidated

Knowledge and Control

Example: recall Hadley v. Baxendale (miller & shipper)

Hadley knew shipment was urgent (but didn’t tell Baxendale)

But Baxendale was the decisionmaker over how fast crankshaft would be shipped

Party that had the information ≠ party that makes the decision

Unilateral Mistake

What if one party does not have full information but the other does?

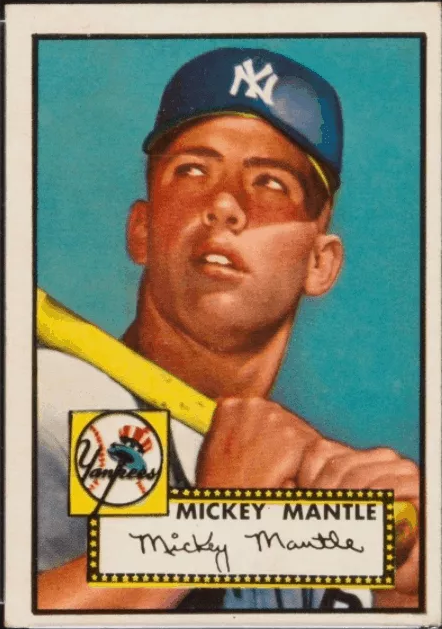

Example: a boy buys a baseball card from a shop, realizes it is worth a lot of money, resells it for large profit

- Shop-owner sues, claiming the original contract was invalid based on mistake

Unilateral Mistake

Courts generally enforce (that is, they don’t invalidate) contracts where there is a unilateral mistake

Beliefs by parties about value of good is subjective and not determinable

- Shop would argue both parties were mistaken

- Boy would argue the seller knew all along the card was worth a lot

- Court has no way to determine which is true

Unilateral Mistake

Why is this efficient?

Contracts based on unilateral mistake generally unite knowledge & control

An enforcing them creates an incentive to gather information prior to agreement

Unilateral Mistake: Laidlaw v. Organ

Laidlaw v. Organ, 15 U.S. 178 (1817)

War of 1812, British blockaded New Orleans

- Price of tobacco fell, since can’t be exported

Organ (buyer) learned the war was over

- Immediately negotiated with Laidlaw to buy a bunch of tobacco at depressed wartime price

Next day, news broke that the war had ended, tobacco price went up

- Laidlaw refused to deliver, Organ sued for breach of contract

Unilateral Mistake: Laidlaw v. Organ

- Supreme Court: “The court is of opinion that [Organ] was not bound to communicate [this information]” to Laidlaw

“It would be difficult to circumscribe the contrary doctrine within proper limits, where the means of intelligence are equally accessible to both parties. But at the same time, each party must take care not to say or do any thing tending to impose upon the other”

Adopts the rule of caveat emptor in American law

Doctrine gets a bit fuzzy from here, not a rock-solid rule

- But in general, unilateral mistake is not a valid reason to void a contract

Uniting Knowledge and Control

Laidlaw establishes that contracts based on unilateral mistake are generally valid

- Agrees with efficiency: these contracts typically unite knowledge and control

Organ didn’t invest time & resouces into seeking out this information for a productive purpose, happened upon it fortuitously

Contract merely accelerated the discovery of public information by one day, didn’t affect tobacco production

Uniting Knowledge and Control

What about Obde v. Schlemeyer (termites case)?

- Also based on unilateral mistake

Court upheld contract, but punished seller for hiding information

- In that case, contract separated knowledge from control

Productive vs. Redistributive Information

Productive information: information that can be used to produce more wealth

Redistributive information: information that can be used to redistribute wealth from an uninformed party to an informed party

Cooter & Ulen: contracts based on one party’s knowledge of:

- productive information should be enforced, especially if result of active investment

- redistributive information, or “fortuitiously acquired” information, should not be enforced