2.7 — Regulation & Takings

ECON 315 • Economics of the Law • Spring 2021

Ryan Safner

Assistant Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/lawS21

lawS21.classes.ryansafner.com

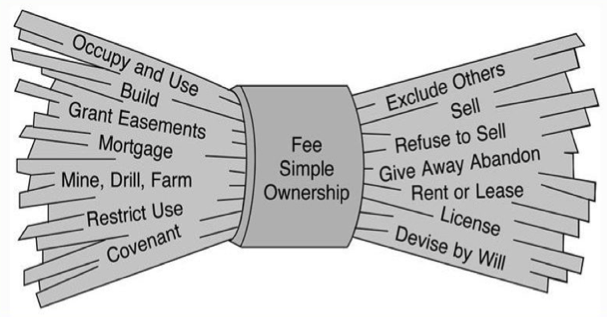

What Would an Efficient Property Law Look Like?

- Recall the 4 questions any property system must answer:

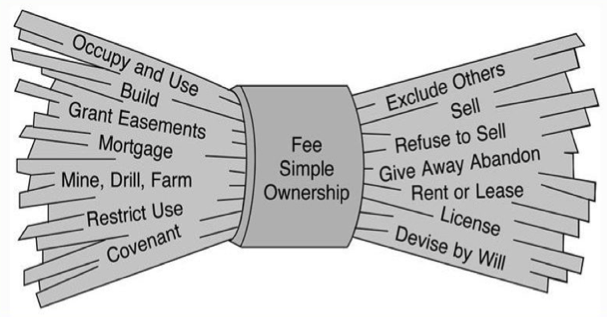

What can be privately owned?

What can (and can't) an owner do with her property?

How are property rights established?

What remedies are available when property rights are violated?

Eminent Domain

Eminent Domain

One potential role for government, provision of public goods

- Markets tend to undersupply due to free rider problem

To do this, government needs land, which may already be owned by private parties

In most countries, governments have right of eminent domain: can seize property when owner does not want to sell

- Also called a “taking” (because that’s what the government is doing!)

Eminent Domain

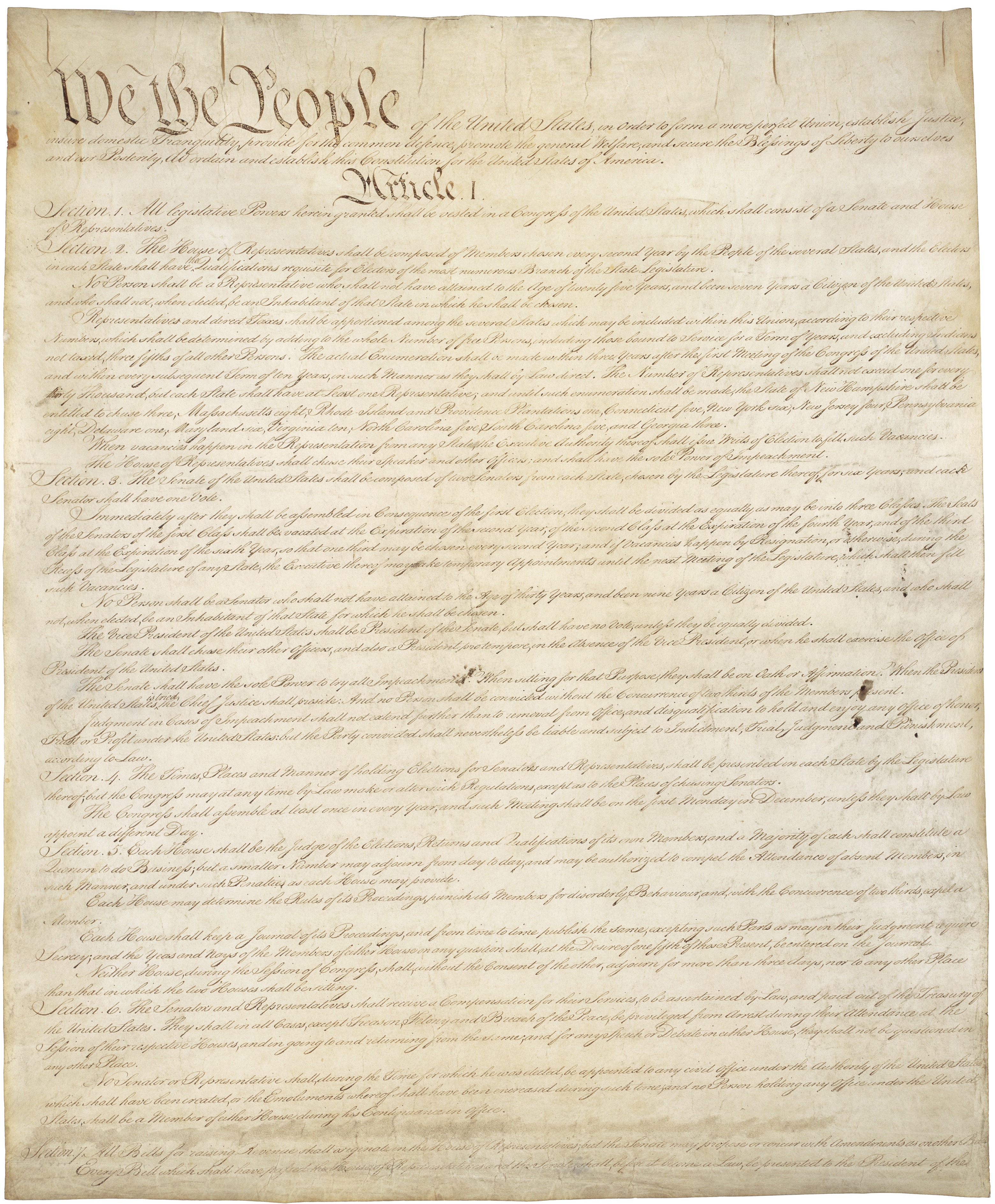

“nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation”

United States Constitution, Amendment V

Eminent Domain: Restrictions

- Constitution constrains government’s ability to seize private property:

- Must be for a “public-use”

- Must provide “just compensation” to subject of taking

Eminent Domain: Restrictions

“Just compensation” consistently interpreted as fair market value, what owner would likely have been able to sell the property for

Note this might be much lower than owner’s subjective value placed on the property

Eminent Domain: Example

Example: Suppose Ann owns an estate whose fair market value is $100,000.

- Ann does not want to sell it because she (subjectively) values the estate at $175,000 for sentimental reasons

Eminent Domain: Example

Example: Suppose Ann owns an estate whose fair market value is $100,000.

Ann does not want to sell it because she (subjectively) values the estate at $175,000 for sentimental reasons

Suppose Bob covets Ann’s estate, and would be willing to pay up to $120,000 for it

Ann values the estate more than Bob, and does not want to sell to him

- The house is efficiently allocated to Ann who values it more

Eminent Domain: Example

Example: Suppose Ann owns an estate whose fair market value is $100,000.

Suppose instead, Bob contributes $10,000 to the Mayor’s political campaign

- The city condemns Ann’s estate via eminent domain, compensating her $100,000 and then sells it to Bob at $100,000

Bob gains $10,000, the Mayor gains $10,000, and Ann loses $75,000

Eminent Domain: Example

Eminent domain prevents Bob from having to pay Ann’s full reservation price ($175,000)

The just compensation requirement for eminent domain alone clearly does not prevent abuse like this

Eminent domain must also be for a public use of the land

Eminent Domain: Public Use

But eminent domain should not be used on a whim to produce any public good

Individuals’ subjective value often is higher than fair market value

- Eminent domain destroys a lot of surplus

Eminent Domain: Public Use

- Example: motorists would be willing to pay $110,000 for a road through Ann’s property

Government forces Ann to sell at $100,000

Eminent domain apparently creates $10,000 in surplus!

But remember, Ann subjectively values her property at $175,000, so really a net social loss of -$65,000!

Eminent Domain: Contiguous properties

Main economic argument for eminent domain’s efficiency: when dealing with contiguous properties government must purchase to provide a public good

Example: a highway that goes through 500 residential properties

- Gov’t must purchase all 500 properties

- A single property along the line unwilling to sell can hold up the entire project

- High transaction costs from strategic bargaining

Eminent Domain: Contiguous properties

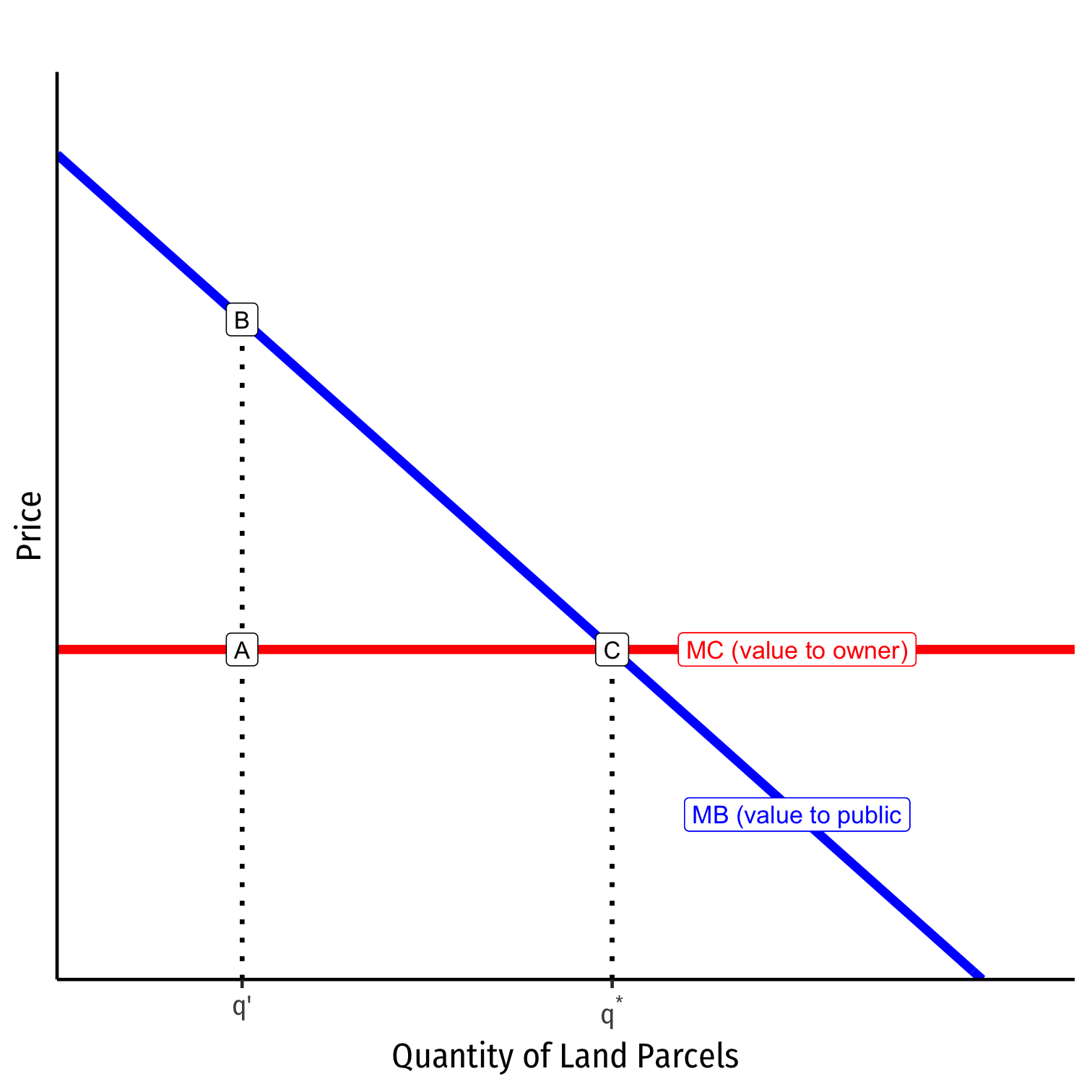

q′: amount of parcels purchased so far

q⋆: optimal number required for public use

A: owner’s reservation price

B: government’s maximum WTP

¯AB bargaining range between parcel owner and government

- for any regular transaction, owner can ask for up to B or walk away

Eminent Domain: Contiguous properties

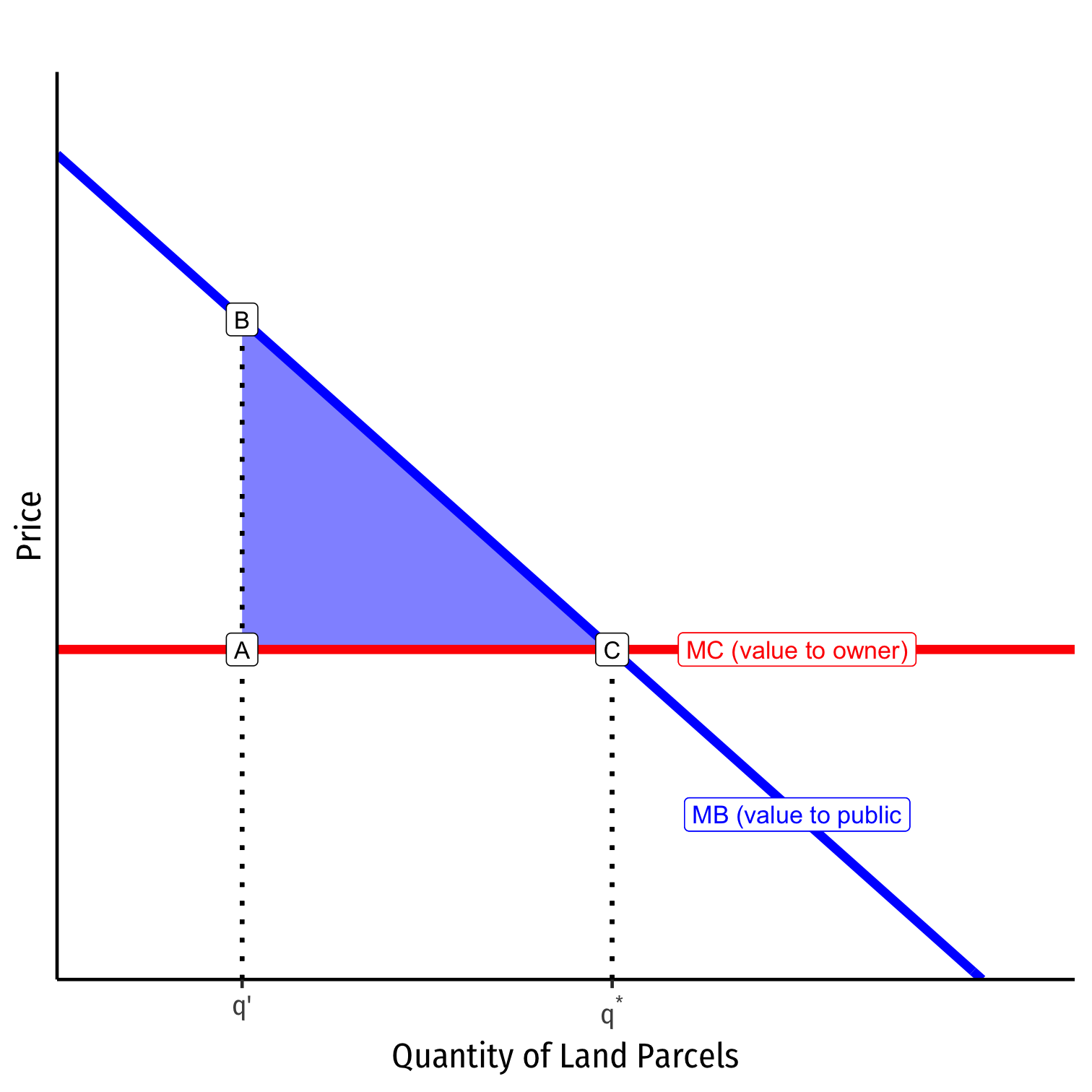

q′: amount of parcels purchased so far

q⋆: optimal number required for public use

A: owner’s reservation price

B: government’s maximum WTP

¯AB bargaining range between parcel owner and government

- for any regular transaction, owner can ask for up to B or walk away

Holdout recognizes he can extract entire surplus ΔABC from government

- Knows government can’t proceed without q′!

Poletown Neighborhood Council v. Detroit

1981, General Motors threatened to close Detroit factory

- 6,000 jobs, millions of dollars in city tax revenue

City used eminent domain to condemn entire neighborhood

- 1,000 homeowners and 100 businesses forced to sell

- land then given to GM for upgraded factory

City claimed employment and tax revenues are public goods, justified taking

Poletown Neighborhood Council v. Detroit

- MI Supreme Court:

“Alleviating unemployment and revitalizing the economic base of the community [are valid public uses]...the benefit to a private interest [GM] is merely incidental”

- Overturned in 2004 County of Wayne v. Hathcock

- found that taking property for developing a private business did not constitute a valid public use

Kelo v. City of New London

Pfizer planned to build large research facility in downtown New London, CT

- City hoped this would attract other businesses

Plaintiffs owned houses on portions of this land

- Would otherwise be difficult to develop this land with sporadic residential properties

Susette Kelo

Kelo v. City of New London

City condemned the houses, claiming “the area was sufficiently distressed to justify a program of economic rejuvenation”

Plaintiffs attorneys argued “If jobs and taxes can be a justification for taking someone's home and business, then no property in America is safe”

CT Supreme Court ruled it a valid public use; U.S. Supreme Court in 2005 concurred (5-4) it was a valid public use

Ironically, Pfizer never built their facility and the land remains undeveloped

Susette Kelo

Kelo v. City of New London

Major political backlash to Kelo case

45 States passed laws or amended their State constitutions to restrict eminent domain power, primarily excluding “economic development” as a valid public use

Susette Kelo

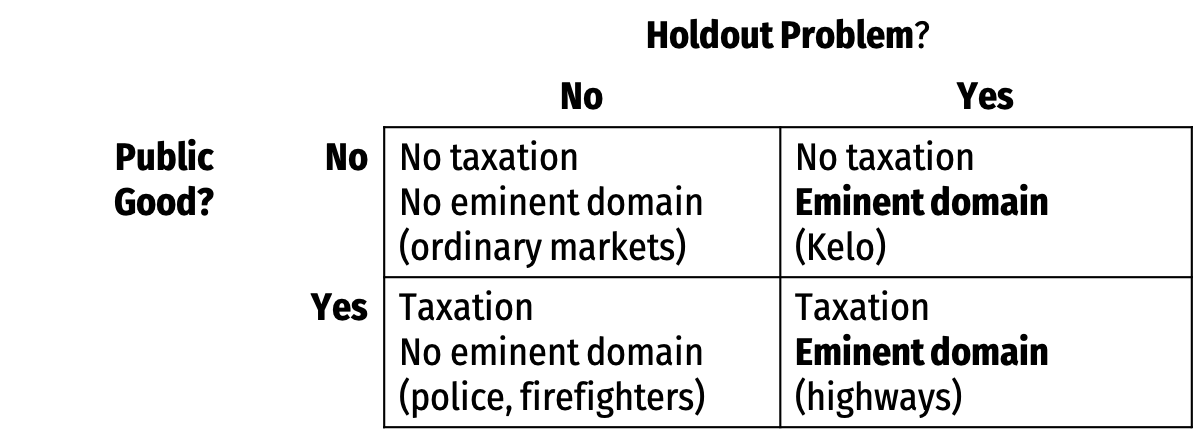

Eminent Domain: Public Use

The law requires that eminent domain be restricted to public uses

Economic efficiency suggests only using eminent domain for dealing with holdout problems (contiguous properties) on high-valued public goods

We can still use taxes to finance public goods and solve the free rider problem

Eminent Domain: Public Use

The law requires that eminent domain be restricted to public uses

Economic efficiency suggests only using eminent domain for dealing with holdout problems (contiguous properties) on high-valued public goods

We can still use taxes to finance public goods and solve the free rider problem

Eminent Domain and Takings

Takings are an involuntary exchange

Possibility of a taking creates uncertainty

- Perverse incentives for State to expropriate private property for its own ends

Unlike taxes, takings concentrate cost on individual owners

- Property owners go to great lengths to protect their property

Lots of potential rent-seeking in “offense” and “defense” & the politics of redistribution

Eminent Domain and Takings

Hence, public use and just compensation constraint

So takings should only be used under limited conditions: for public use and with just compensation, when transaction costs (hold out problems, etc) preclude the government’s purchase by consent

Regulation

Regulation

Regulation ≈ any constraints on use of private property

The State has broad authority to regulate via the police power, often to promote “health, safety, morals and the general welfare”

If a regulation diminishes the value of property enough, considered a taking that requires just compensation

When Is a Regulation a Taking?

Several legal tests that developed over time

Physical invasion test: if regulation involves any physical invasion of the property by government, just compensation is due

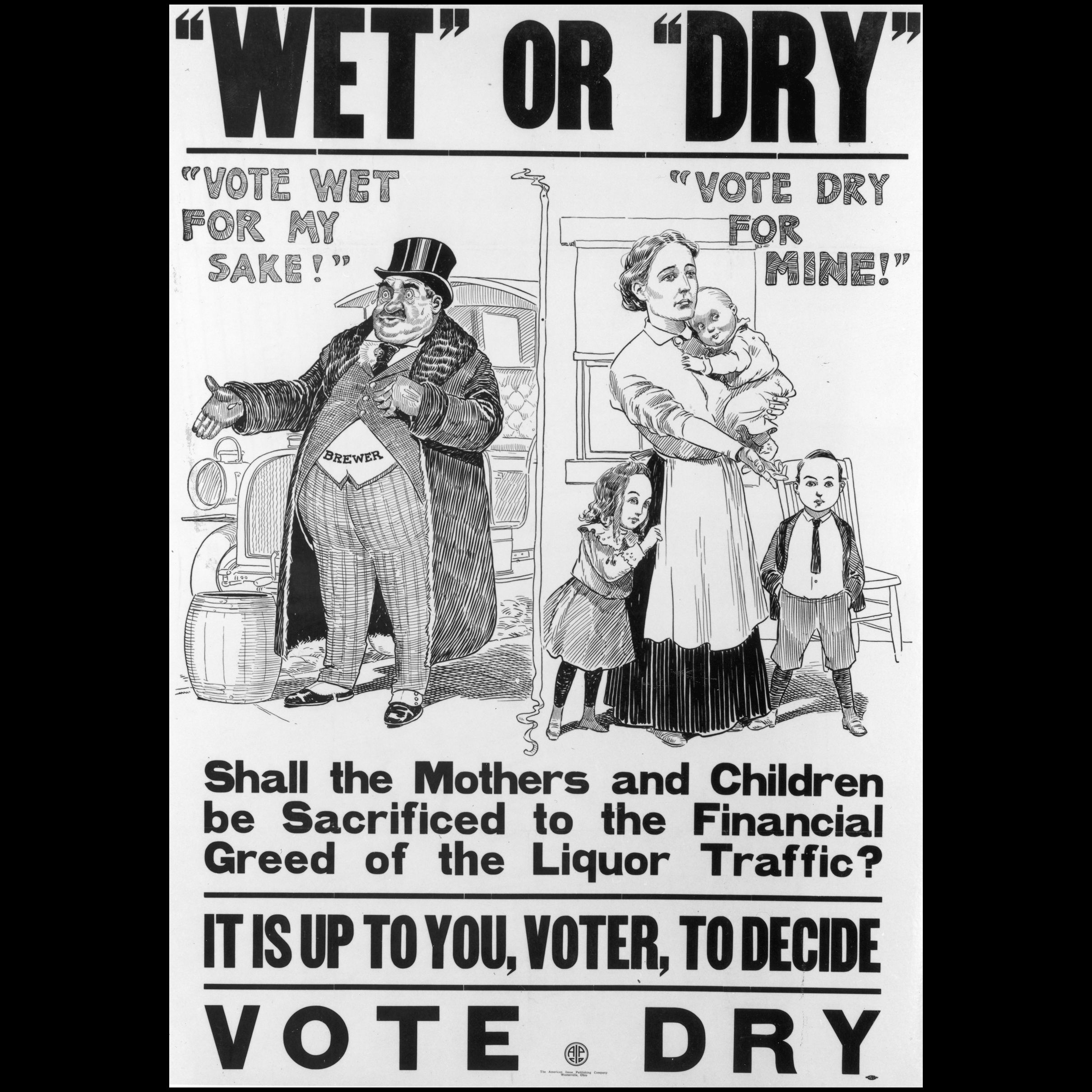

Noxious Use Doctrine

Mugler v. Kansas 1887

- Kansas passed a law prohibiting the manufacture of liquor without a permit, judging it to be a nuisance

- Mugler owned a brewery, sued: this is a taking, demands just compensation

Kansas Supreme Court upheld the law; U.S. Supreme Court upheld the law as well, creating the noxious use doctrine

- regulations curbing noxious uses of property injurious to health, safety, morals are consistent with police power, do not require compensation

Diminution of Value

Pennsylvania Coal v. Mahon 1922

In late 1800s, PA Coal purchased mineral and support rights tied to a piece of land, Mahon owned the surface rights

1921 PA legislature passed the Kohler Act, prohibiting:

“mining of anthracite coal in such a way as to cause the subsidence of, among other things, any structure used as a human habitation”

- PA Coal sued PA government, claiming this destroyed the value of their property, and requires compensation as a taking

Pennsylvania Coal v. Mahon

Pennsylvania Coal v. Mahon 1922

Lower court sided with government

U.S. Supreme Court sided with PA Coal, that the regulation substantially diminished the (economic) value

Pennsylvania Coal v. Mahon: Majority Opinion

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

1841—1935

Associate Justice of U.S. Supreme Court

“What makes the right to mine coal valuable is that it can be exercised with profit. To make it commercially impracticable to mine certain coal has very nearly the same effect for constitutional purposes as appropriating or destroying it. This we think that we are warranted in assuming that the statute does...”

“The general rule at least is, that while property may be regulated to a certain extent, if regulation goes too far it will be recognized as a taking.”

Pennsylvania Coal v. Mahon: Dissent

Louis Brandeis

1856—1941

Associate Justice of U.S. Supreme Court

“Every restriction upon the use of property imposed in the exercise of the police power deprives the owner of some right theretofore enjoyed, and is, in that sense, an abridgment by the States of rights in property without making compensation. But restriction imposed to protect the public health, safety or morals from dangers threatened is not a taking. The restriction here in question is merely the prohibition of a noxious use. The property so restricted remains in the possession of its owner. The State does not appropriate it or make any use of it. The State merely prevents the owner from making a use which interferes with paramount rights of the public.”

Diminution of Value

Famously, a lot of debate between Holmes & Brandeis’ opinions of this famous case

But they both agree on the law, they disagree about the facts

- Law: if regulation “goes too far” in diminishing value, compensation is owed

- Holmes: harm from regulation > harm from PA Coal’s externality, went too far

- Brandeis: harm from PA Coal’s externality > harm from regulation, did not go too far

Blume and Rubinfeld

Blume and Rubinfeld (1984) argue that compensation for takings is efficient

Shifts the burden of regulation’s cost from small group (property owners affected) to large group (all taxpayers)

Normally, these are zero-sum transfers (no effect on efficiency)...so long as we assume risk-neutrality

Blume, Lawrence and Daniel L. Rubinfeld, 1984, “Compensation for Takings: An Economic Analysis,” California Law Review 72(4): 569-628

Blume and Rubinfeld

But if people are risk-averse, compensation effectively acts as an insurance policy against regulatory harms

If insurance against regulatory harm was offered on the market, people would probably buy it

- But private insurers do not provide this, for normal market failure reasons (adverse selection, moral hazard, etc)

Blume, Lawrence and Daniel L. Rubinfeld, 1984, “Compensation for Takings: An Economic Analysis,” California Law Review 72(4): 569-628

Blume and Rubinfeld

- Requiring government to provide compensation for regulatory takings provides exactly this form of insurance

- By compensating owners after harm occurs, spreads cost of regulation over everyone

Blume, Lawrence and Daniel L. Rubinfeld, 1984, “Compensation for Takings: An Economic Analysis,” California Law Review 72(4): 569-628

Wrapping Up Property Law

- Recall the 4 questions any property system must answer:

What can be privately owned?

What can (and can't) an owner do with her property?

How are property rights established?

What remedies are available when property rights are violated?

Wrapping Up Property Law

Main set of questions: what are the benefits and costs of:

- having property rights (at all)?

- expanding property rights to cover more things?

- introducing an exception/limitation to property rights?

In what circumstances will benefits > costs?

Coming up next: contract law