2.5 — Property Acquisition & Use

ECON 315 • Economics of the Law • Spring 2021

Ryan Safner

Assistant Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/lawS21

lawS21.classes.ryansafner.com

What Would an Efficient Property Law Look Like?

- Recall the 4 questions any property system must answer:

What can be privately owned?

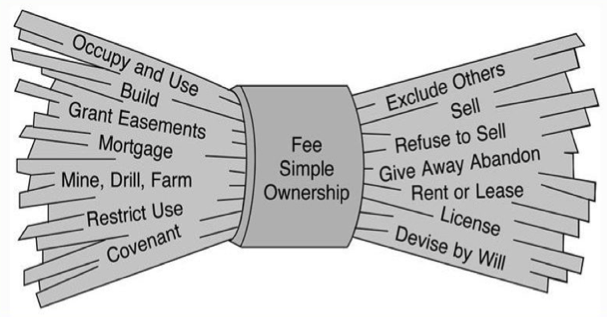

What can (and can't) an owner do with her property?

How are property rights established?

What remedies are available when property rights are violated?

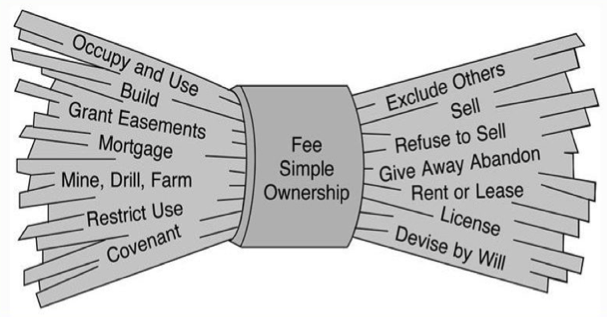

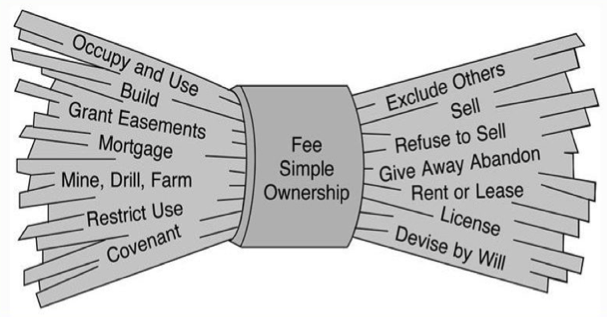

Exercising Property Rights

Exercising Property Rights

William Blackstone

(1723-1780)

“There is nothing which so generally strikes the imagination, and engages the affections of mankind, as the right of property; or that sole and despotic dominion which one man claims and exercises over the external things of the world, in total exclusion of the right of any other individual in the universe.”

Blackstone, William, Commentaries on the Laws of England (1765-1769) Book II, Chapter 1 - Of Property in General

Exercising Property Rights

Efficiency would suggest the maximum liberty principle: owners should be able to do whatever they please with their property

- whatever creates the most value for the owner (subjective)

...provided they do not interfere with others' property or rights

Similar to Millian Harm Principle

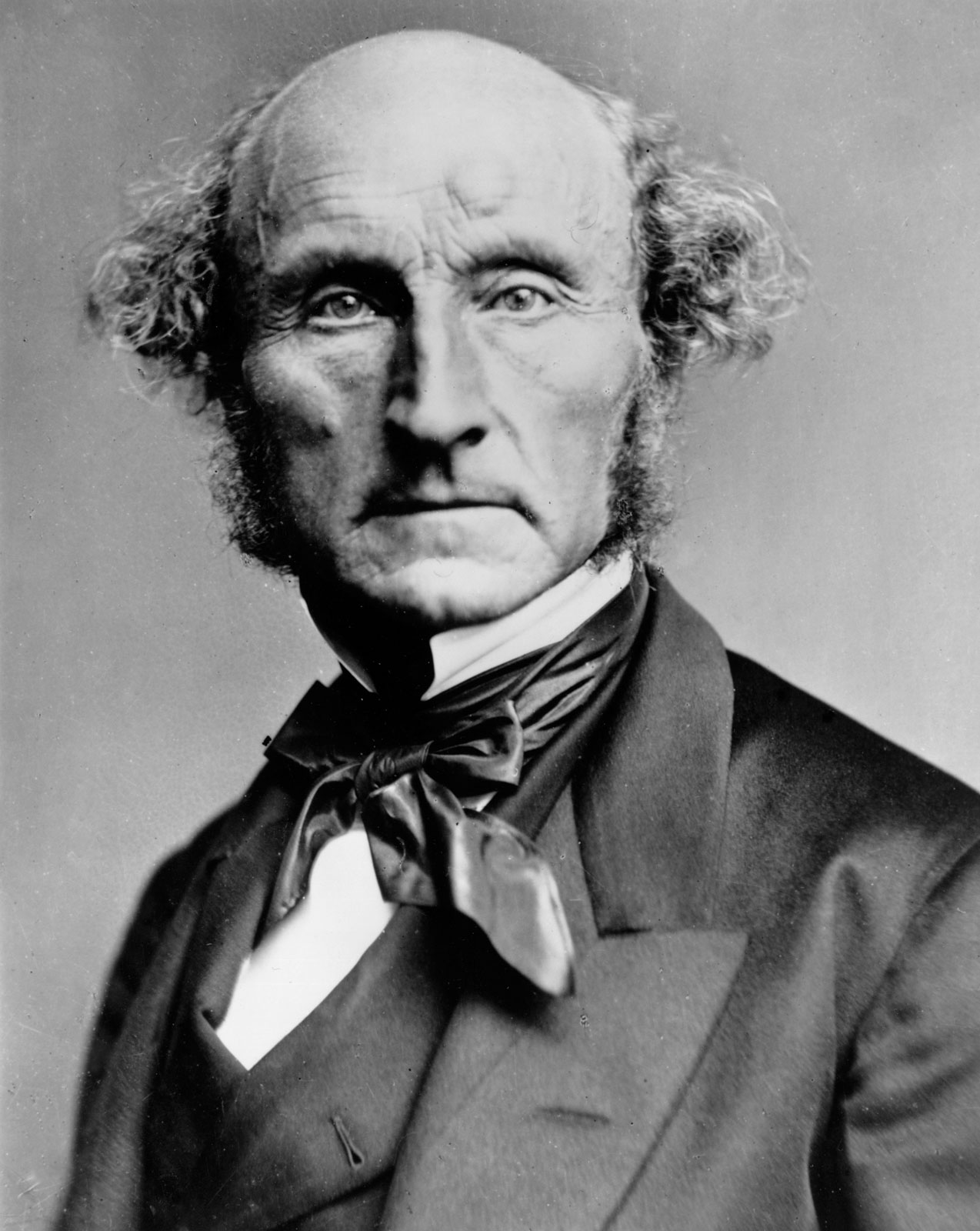

John Stuart Mill

1806-1873

- On Liberty: establish proper relationship between government and people

- One of the greatest defenses of freedom of speech ever written

- The “harm principle”: people should be free to do anything they please so long as does no harm to others

Mill, John Stuart, On Liberty

Exercising Property Rights

Put economically: property owners should be at liberty to do as they please, so long as their actions do not impose an externality on others

In common law, an externality is called a nuisance

Exercising Property Rights

Common law appears to approximate the maximum liberty principle

But does it really?

- legislatures pass laws affecting property

- bans on repugnant markets

- regulation

Nice theoretical idea, but not necessarily a fundamental legal maxim

Back to Remedies: Nuisance Law

Nuisance Law

Law distinguishes between different scales of externalities (nuisances):

Affecting only a few people, a private nuisance or a private bad

- low transaction costs ⟹ injunctions are preferable

Affecting a large number of people, a public nuisance, a public bad

- high transaction costs ⟹ damages are preferable

Types of Damages

Compensatory damages intended to “make the victim whole” by compensating for actual harm done

Temporary: compensate for past harms that have already occurred

- parties must return to court if harm continues

- court must keep calculating the amount of damages each instance

- higher transaction costs

- but incentivizes injurers to invest in reducing future harms

Types of Damages

Compensatory damages intended to “make the victim whole” by compensating for actual harm done

Permanent: cover (present value of) anticipated future harm

- a one-time, permanent fix

- less costly for court to implement, but harder to estimate accurate value

- but no incentive to reduce harm (have already “purchased the right to harm”) with new technology

Efficient Nuisance Remedies

For a private nuisance affecting small number of people, injunction is more efficient remedy

For a public nuisance affecting large number of people, damages are more efficient remedy

- If damages easy to measure & innovation occurs rapidly, temporary damages more efficient

- If damages hard to measure & innovation occurs slowly, permanent damages more efficient

What is done in practice for public nuisances?

Boomer v. Atlantic Cement Co

Boomer v. Atlantic Cement Co. 26 N.Y.2d 219, 309 N.Y.S.2d 312 (N.Y. 1970)

- Atlantic owned large cement plant near Albany NY (worth $45 million, 300 employees)

- production resulted in dirt, smoke, vibration

- neighbors sued for an injunction to close the plant

- court found plant to be a nuisance, awarded $183,000 in damages

- neighbors appealed, requesting an injunction

Boomer v. Atlantic Cement Co

- NY Appeals Court ruled:

- this was a valid nuisance case

- nuisances are generally remedied with injunctions

- but harm of closing the plant > amount of damages done

- so refused to issue an injunction

- ordered permanent damages, paid “as servitude to the land”

- effectively priced into adjoining land

Boomer v. Atlantic Cement Co

Harm to neighbors ($183,000) much less than the value of the investment in the factory ($45 million), would be inefficient to close the factory

If transaction costs were low, neighbors could bargain with plant to mitigate harm (pay it to reduce dirt, smoke, vibrations, etc)

But high transactions costs here (a public nuisance), so court imposed a liability rule to compensate the injured parties

- keeps plant in operation, property right kept in hands of the more-valued use

First recognition that sometimes a liability rule is more efficient in some property cases

Boomer v. Atlantic Cement Co

“[Ordinarily in property law], where a nuisance has been found and where there has been any substantial damage shown by the party complaining, an injunction will be granted.”

“To grant the injunction unless defendant pays plaintiffs such permanent damages as may be fixed by the court seems to do justice between the contending parties. All of the attributions of economic loss to the properties on which plaintiffs' complaints are based will have been redressed ... [and i]t seems reasonable to think that the risk of being required to pay permanent damages to injured property owners by cement plant owners would itself be a reasonably effective spur to research for improved techniques to minimize nuisance.”

“[The initial trial court is ordered] to grant an injunction which shall be vacated upon payment by defendant of.. .permanent damage[s] to the respective plaintiffs.”

Establishing Property Rights

What Would an Efficient Property Law Look Like?

- Recall the 4 questions any property system must answer:

What can be privately owned?

What can (and can't) an owner do with her property?

How are property rights established?

What remedies are available when property rights are violated?

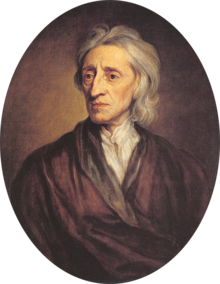

Lockean Political Philosophy of Property

John Locke

1632-1704

"Though the earth, and all inferior creatures, be common to all men, yet every man has a property in his own person: this no body has any right to but himself. The labour of his body, and the work of his hands, we may say, are properly his. Whatsoever then he removes out of the state that nature hath provided, and left it in, he hath mixed his labour with, and joined to it something that is his own, and thereby makes it his property...that excludes the common right of other men: for this labour being the unquestionable property of the labourer, no man but he can have a right to what that is once joined to, at least where there is enough, and as good, left in common for others," (Ch. V).

Locke, John, 1689, Second Treatise on Government

Who Owns Fugitive Property?

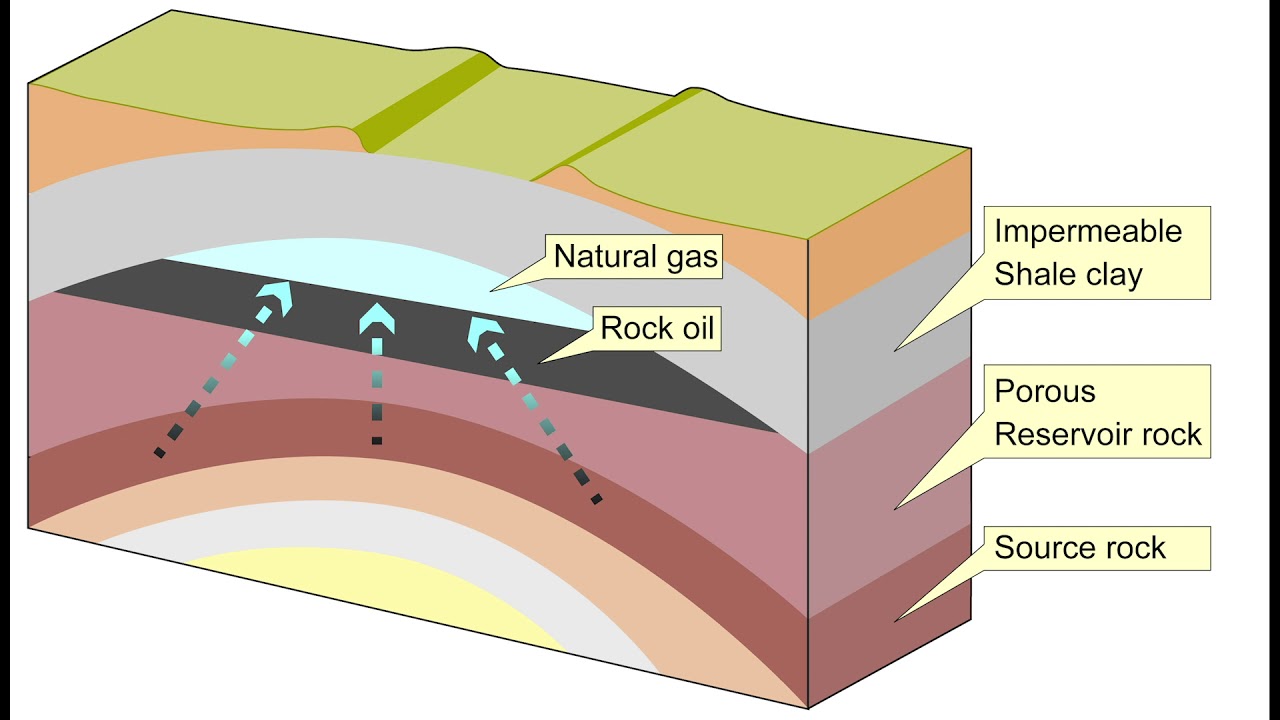

Fugitive property: property that moves around or has indefinite boundaries (the harder cases)

Examples: oil & gas deposits, whales, foxes

Who Owns Fugitive Property?

Hammonds v. Central Kentucky Natural Gas Co. 75 S.W.2d 204 (Ky. Ct. App. 1934)

Central KY leased land lying above natural gas deposits

Geological dome lay partly under Hammonds' land

Central KY drilled down and extracted the gas

Hammonds sued, claiming (some of) the gas was his

Drainage

Two Principles for Establishing Ownership

1) First possession

nobody owns fugitive property until someone possesses it

first to “capture” a resource owns it

Example: Central KY would own all the gas

Two Principles for Establishing Ownership

2) Tied ownership

ownership of fugitive property tied to (possession of) something else (e.g. surface)

- ownership determined before resource is extracted

Example: Hammonds would own some of the gas (under his land)

Tied using principles of accession: new thing owned by owner of the proximate or prominent property

First Possession and Rent-Seeking

- First possession is simpler rule to apply (easy to determine who possessed property first)

“Possession is nine-tenths of the law”

- But incentive for rent-seeking! Invest too many (offsetting) resources into getting there first

First Possession and Rent-Seeking

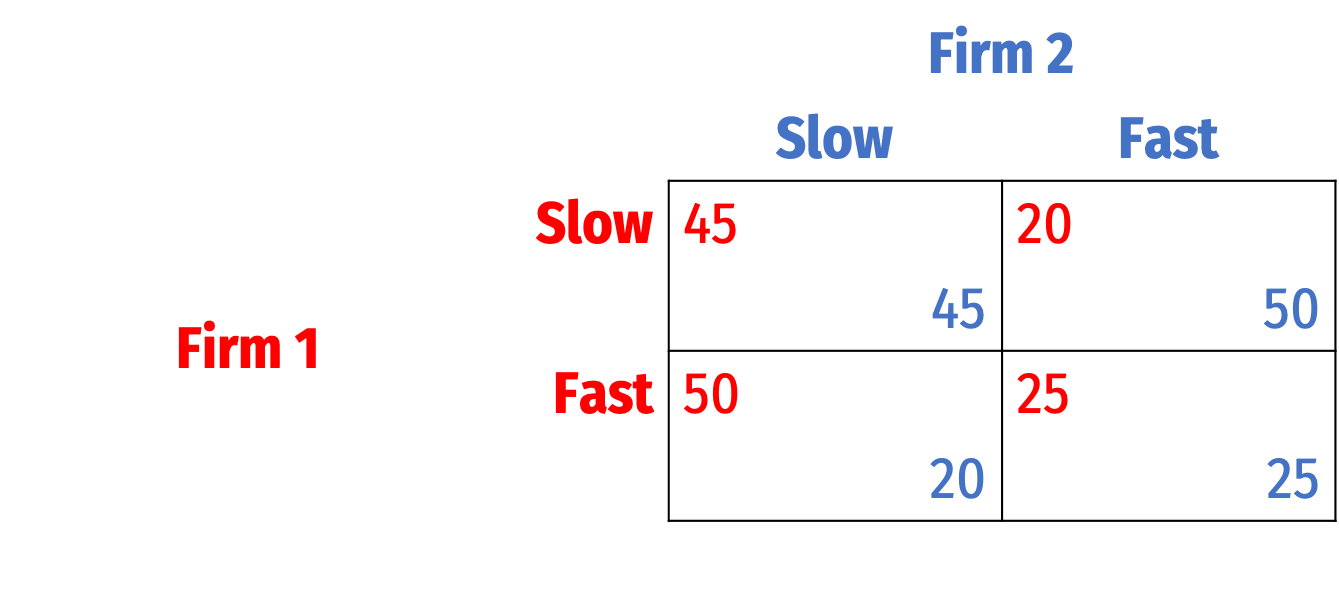

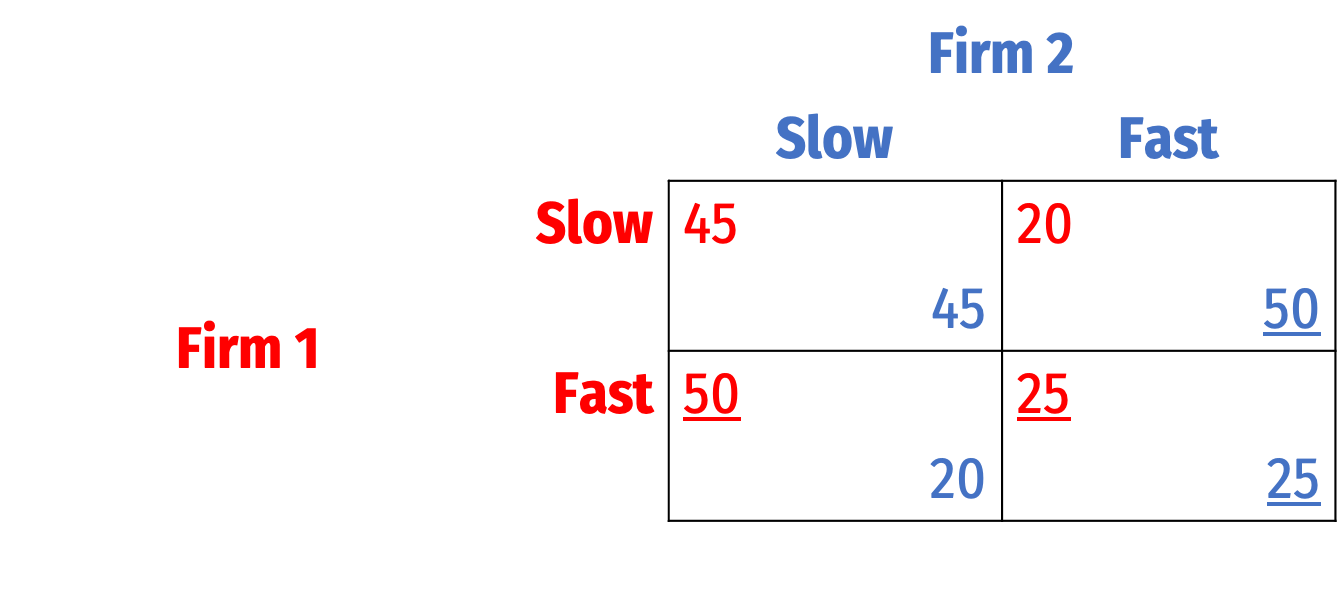

Example: Firm 1 and Firm 2 can drill on an area of unowned land.

Suppose:

- Gas is worth 100

- Drilling slow costs 5, drilling fast costs 25

- If one drills faster than the other, gets 75%/25% of the gas

- If both same speed, split the gas 50%/50%

- Principle of first possession

First Possession and Rent-Seeking

Example: Firm 1 and Firm 2 can drill on an area of unowned land.

Nash Equilibrium: (Fast, Fast)

A prisoners' dilemma

- Pareto-improving change to (Slow, Slow), but not a Nash Equilibrium

Equally viewed as tragedy of the commons

Tied Ownership

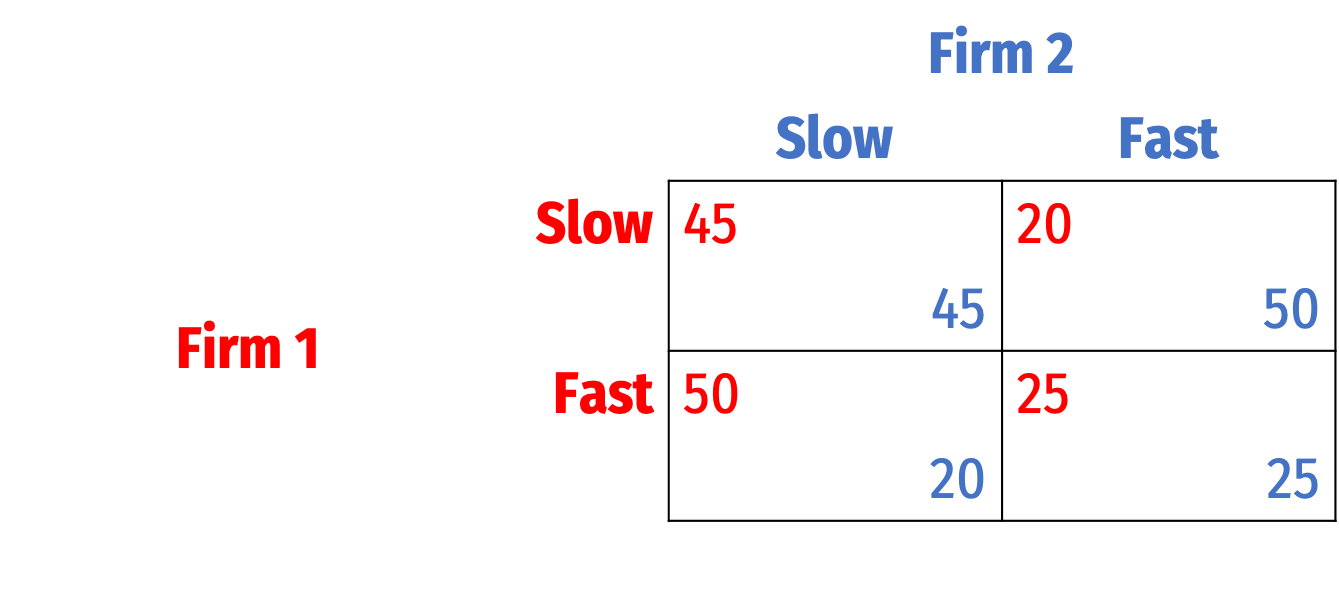

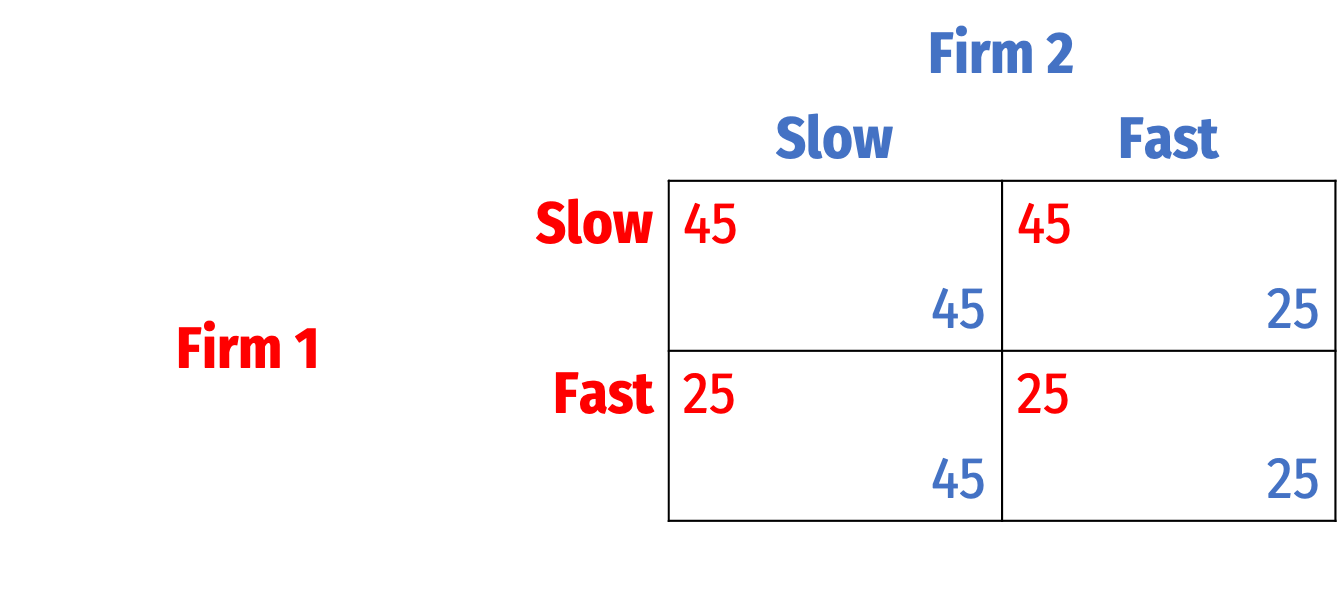

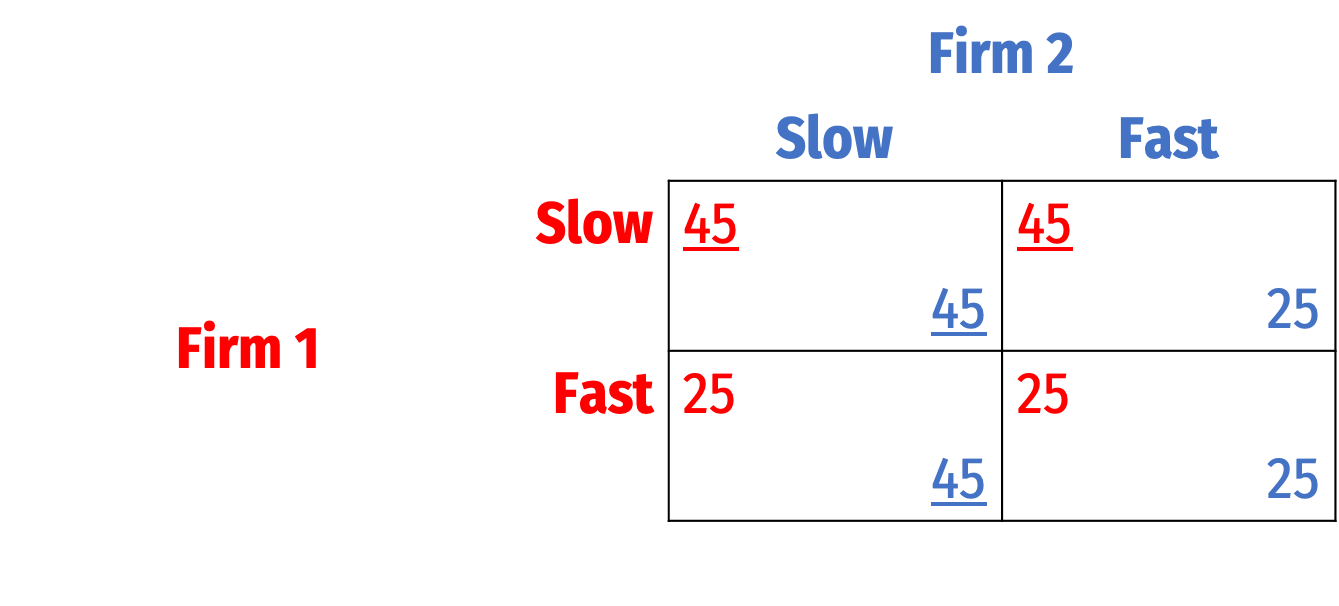

Example: Firm 1 and Firm 2 can drill on an area of unowned land.

- Suppose instead, principle of tied ownership

- Firms have clear rights to surface, know that however quickly they drill, they have rights to the gas based on their surface ownership

- No reason not to drill slowly (carefully, efficiently)!

Tied Ownership

Example: Firm 1 and Firm 2 can drill on an area of unowned land.

Nash Equilibrium: (Slow, Slow)

Incentivizes efficient use of resource

No need to race to get it first

But perhaps difficult to establish and verify ownership rights

The Tradeoff Again

Rules that link ownership to possession

- Pro: easy to administer

- Con: incentivize uneconomic investment in possessory acts (rent-seeking)

Rules that allow ownership without possession (like tied ownership)

- Pro: avoids rent-seeking, incentivizes efficient stewardship of resource

- Con: costly to administer & clarify ownership

The Tradeoff Again

Rules that link ownership to possession

- “Fast-fish, loose-fish” from whaling

- Post (the saucy intruder) claiming the fox

Rules that allow ownership without possession (like tied ownership)

- “Iron holds the whale” from whaling

- Pierson (the original hunter) keeping the fox

Example: The Homestead Act of 1862

Intended to settle the Western U.S. after Civil War

Citizens could acquire 160 acres of land for free:

- as head of a family, or 21 years old

- “for the benefit of actual cultivation, and not...for the use or benefit of someone else”

- must live on claim for 6 months and make “suitable” improvements

Example: The Homestead Act of 1862

Essentially a first possession rule for land

Friedman: caused people spend inefficiently much to gain ownership of the land

Example: The Homestead Act of 1862

David D. Friedman

(1945—)

“The year is 1862; the piece of land we are considering is… too far from railroads, feed stores, and other people to be cultivated at a profit...The efficient rule would be to start farming the land the first year that doing so becomes profitable, say 1890. But if you set out to homestead the land in 1890, you will get an unpleasant surprise: someone else is already there...If you want to get the land you will have to come early. By farming it at a loss for a few years you can acquire the right to farm it thereafter at a profit.”

Example: The Homestead Act of 1862

David D. Friedman

(1945—)

“How early will you have to come? Assume the value of the land in 1890 is going to be $20,000, representing the present value of the profit that can be made by farming it from then on.Further assume that the loss from farming it earlier than that is $1,000 a year.If you try to homestead it in 1880, you again find the land already taken.Someone who homesteads in 1880 pays $10,000 in losses for $20,000 in real estate – not as good as getting it for free, but still an attractive deal...The land will be claimed about 1870, just early enough so that the losses in the early years balance the later gains. It follows that the effect of the Homestead Act was to wipe out, in costs of premature farming, a large part of the land value of the United States.”

What Can Be Privately Owned?

What Would an Efficient Property Law Look Like?

- Recall the 4 questions any property system must answer:

What can be privately owned?

What can (and can't) an owner do with her property?

How are property rights established?

What remedies are available when property rights are violated?

Public vs. Private Goods

Public Good: a good that is non-rival and non-excludable

Rivalry: one use of a resource removes it from other uses

Excludability: ability or right to prevent others from using it (ownership)

Public vs. Private Goods

Individual bears a private cost to contribute, but only gets a small fraction of the (dispersed) benefit of a good

If individuals can gain access to the good (nonexcludable) without paying, may lead to...

Free riding: individuals consume the good without paying for it

Public vs. Private Goods

When private goods are owned publicly, they tend to be overused, congested, and depleted (tragedy of the commons)

When public goods are owned privately, they tend to be underproduced

Implications for efficiency:

- Private goods should be privately owned

- Public goods should be publicly provided/regulated

Public vs. Private Goods

This is consistent with the normative framework we have been developing:

Low transaction costs → facilitate exchange

- Private goods — low transaction costs

- Private ownership facilitates exchange

High transaction costs → allocate rights efficiently

- Public goods — high transaction costs

- Public provision/regulation to get efficient amount

Alternative Approach: Transaction Costs

Example: Consider clean air

- A large number of parties affected ⟹ high transaction costs ⟹ injunctive relief unlikely to work well

But still two options:

- give property owners a right to clean air, protected by damages

- public regulation

Alternative Approach: Transaction Costs

Example: Consider clean air

- A large number of parties affected ⟹ high transaction costs ⟹ injunctive relief unlikely to work well

Compare the relative costs of each option

- Damages: legal costs of lawsuits

- Regulation: administrative costs, politics

When To Privatize a Resource

We've seen two doctrines for how ownership rights are determined

When should a resource become privately owned?

- Cost of private ownership: owners must take steps to make the resource excludable: boundary maintenance

- Cost of public ownership: congestion and overuse (tragedy of the commons)

Efficient to privatize a resource where boundary maintenance costs are less than the waste from overuse of the resource

Remember the lesson & example in Demsetz (1967)!

How to Give Up (Or Lose) Property Rights

Adverse possession (“squatter's rights”): if you occupy someone else's property for long enough, you become the legal owner, provided:

- occupation was adverse to the owner's interests

- owner did not object or take legal action

Benefit: reduces uncertainty over time; allows (otherwise idle) land to be put to use

- Again, “possession is nine-tenths of the law”

Cost: owners must incur monitoring costs to protect property

How to Give Up (Or Lose) Property Rights

Estray statutes laws governing lost and found property

- procedures for finder to establish ownership of lost or abandoned property

- often if original owner is not located within a period of time, ownership belongs to the finder

Discourages theft (thief can't just say “I found it”), increases information spread about lost property

Assuming owners value the property the highest, ensures it gets back to them

Limitations to Property Rights

Property rights generally are protected by injunctive relief (property rules), BUT

Ploof v. Putnam 81 Vt. 471, 71 A. 188 (1908)

- Ploof sailing with family on Lake Champlain, storm erupted

- Tied up boat to pier on island owned by Putnam

- Putnam's employee cut the boat loose, Ploof sued

- Court found for Ploof: private necessity is a valid defense for trespass

Limitations to Property Rights

Property rights are not absolute!

Example: in an emergency, it is lawful to violate another's property rights, but must still compensate them for damages

- more efficient to use a liability rule here (high transaction costs, no time for bargaining in an emergency)