2.3 — Bargaining & Transaction Costs

ECON 315 • Economics of the Law • Spring 2021

Ryan Safner

Assistant Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/lawS21

lawS21.classes.ryansafner.com

Some Bargaining Theory

Some Bargaining Theory

Example: Your car is worth $3,000 to you, and $4,000 to me. Suppose I have $10,000 to spend.

“Threat point” or “BATNA” or “outside option” is value we each get if we don't exchange:

- Mine: $10,000

- Yours: $3,000

Any outcome we both consent to must make each of us at least as well off as our respective BATNA

Some Bargaining Theory

- If we don't exchange, payoffs are:

- Me: $10,000

- You: $3,000

- Joint: $13,000

Some Bargaining Theory

If we don't exchange, payoffs are:

- Me: $10,000

- You: $3,000

- Joint: $13,000

If I purchase your car at price P, payoffs are:

- Me: 4,000+10,000-P = 14,000-P

- You: P

- Joint: 14,000 (14,000-P+P)

Some Bargaining Theory

If we don't exchange, payoffs are:

- Me: $10,000

- You: $3,000

- Joint: $13,000

If I purchase your car at price P, payoffs are:

- Me: 4,000+10,000-P = 14,000-P

- You: P

- Joint: 14,000 (14,000-P+P)

A $1,000 gain from exchange or cooperative surplus

- Exchange increases our joint payoff by $1,000

Some Bargaining Theory

A $1,000 gain from exchange or cooperative surplus

- Exchange increases our joint payoff by $1,000

Further challenge to agree how to divide the surplus

- fairness

- relative BATNAs

- bargaining skill, threats, promises, etc

Many theories of bargaining, game theory, seek to answer this challenge

- Not our focus right now

Some Bargaining Theory

A $1,000 gain from exchange or cooperative surplus

- Exchange increases our joint payoff by $1,000

Suppose we simply split the surplus equally

- I pay you $3,500 for the car

Our resulting payoffs:

- Me: $10,000 \(\rightarrow\) $10,500 (+$500)

- You: $3,000 \(\rightarrow\) $3,500 (+$500)

- Joint: $13,000 \(\rightarrow\) $14,000 (+$1,000)

Returning to the Farmer and Rancher Example

Example:

- Potential crop damage: $500

- Rancher can build fence for $400

- Farmer can build fence for $200

Suppose we're under a regime of Farmer's rights: Rancher is liable for any crop damage

What does Coasian logic predict will happen?

Farmer and Rancher Example: Farmer's Rights

Example:

- Potential crop damage: $500

- Rancher can build fence for $400

- Farmer can build fence for $200

Suppose we're under a regime of Farmer's rights: Rancher is liable for any crop damage

What does Coasian logic predict will happen?

- The efficient outcome: Rancher will pay farmer to build fence

- How much will the Rancher pay to farmer?

Farmer and Rancher Example: Farmer's Rights

Example:

- Potential crop damage: $500

- Rancher can build fence for $400

- Farmer can build fence for $200

- Consider Farmer's perspective:

- Rancher is liable for all damage, no reason for Farmer to do anything!

- BATNA payoff: 0

Farmer and Rancher Example: Farmer's Rights

Example:

- Potential crop damage: $500

- Rancher can build fence for $400

- Farmer can build fence for $200

- Consider Rancher's perspective:

- Rancher is liable for all damage, Farmer isn't going to do anything

- If he does nothing, will have to pay -$500 damages

- Or spend -$400 to build a fence

- BATNA payoff: -$400 (building fence)

Farmer and Rancher Example: Farmer's Rights

Example:

- Potential crop damage: $500

- Rancher can build fence for $400

- Farmer can build fence for $200

- Farmer's BATNA: $0

- Rancher's BATNA: -$400

Joint payoff: -$400

Efficient outcome: Rancher to pay Farmer some money for Farmer to build fence

- Joint payoff increases to $-200, a $200 gain from cooperation

Farmer and Rancher Example: Farmer's Rights

Example:

- Potential crop damage: $500

- Rancher can build fence for $400

- Farmer can build fence for $200

Basic prediction of bargaining theory: Rancher will pay Farmer something between $200 and $400 to build the fence

- Exactly where depends on their relative bargaining strengths

For simplicity, let's assume a 50-50 split of the gains to cooperation ($200)

Farmer and Rancher Example: Farmer's Rights

Example:

- Potential crop damage: $500

- Rancher can build fence for $400

- Farmer can build fence for $200

Rancher gives $300 to Farmer to build fence

Farmer's payoff: 0 + (0.5 \(\times\) 200) = 100

Rancher's payoff: -400 + (0.5 \(\times\) 200) = -300

Farmer and Rancher Example: Farmer's Rights

| Farmer's Rights | |

|---|---|

| Rancher's BATNA | -400 |

| Farmer's BATNA | 0 |

| Joint Payoff (BATNAs) | -400 |

| Gains from Coop. | 200 |

| Rancher's Payoff from Deal | -300 |

| Farmer's Payoffs from Deal | 100 |

| Joint Payoff (Deal) | -200 |

Farmer and Rancher Example: Rancher's Rights

Example:

- Potential crop damage: $500

- Rancher can build fence for $400

- Farmer can build fence for $200

- Suppose instead, we're under a regime of Rancher's rights: rancher is not liable for any crop damage

Farmer and Rancher Example: Rancher's Rights

Example:

- Potential crop damage: $500

- Rancher can build fence for $400

- Farmer can build fence for $200

- Consider Rancher's perspective:

- Rancher is not liable for any damage, no reason to do anything!

- BATNA payoff: 0

Farmer and Rancher Example: Rancher's Rights

Example:

- Potential crop damage: $500

- Rancher can build fence for $400

- Farmer can build fence for $200

- Consider Farmer's perspective:

- Rancher is not liable for damage, won't do anything

- Farmer can build do nothing and suffer -$500 from damage, or build fence for -$200 and incur no damage

- BATNA payoff: -$200 (build fence)

Farmer and Rancher Example: Rancher's Rights

| Farmer's Rights | Rancher's Rights | |

|---|---|---|

| Rancher's BATNA | -400 | 0 |

| Farmer's BATNA | 0 | -200 |

| Joint Payoff (BATNAs) | -400 | -200 |

| Gains from Coop. | 200 | 0 |

| Rancher's Payoff from Deal | -300 | 0 |

| Farmer's Payoffs from Deal | 100 | -200 |

| Joint Payoff (Deal) | -200 | -200 |

Farmer and Rancher Example: Rancher's Rights

| Farmer's Rights | Rancher's Rights | |

|---|---|---|

| Rancher's BATNA | -400 | 0 |

| Farmer's BATNA | 0 | -200 |

| Joint Payoff (BATNAs) | -400 | -200 |

| Gains from Coop. | 200 | 0 |

| Rancher's Payoff from Deal | -300 | 0 |

| Farmer's Payoffs from Deal | 100 | -200 |

| Joint Payoff (Deal) | -200 | -200 |

Coase Theorem: most efficient outcome (farmer builds fence), maximized joint payoff, is identical under either rule! (Note distribution (final payoffs to each party) is different!)

Note there is no need for a transaction in the 2nd rule, Farmer builds fence on own

One More Example: Party

Example: You want to have a party in your house next to mine.

- You value having the party at $150

- I value a good night's sleep at $100

Efficient for you to have the party

If parties are allowed, no need for negotiation, you will have the party

- No gains from cooperation (my WTP < your WTA)

One More Example: Party

Example: You want to have a party in your house next to mine.

- You value having the party at $150

- I value a good night's sleep at $100

Efficient for you to have the party

If parties are not allowed:

- My BATNA: 0

- Your BATNA: 0

- Gains from cooperation: 50

- If split evenly, you pay me $125 to have the party

The Benefits & Costs of Property Rights

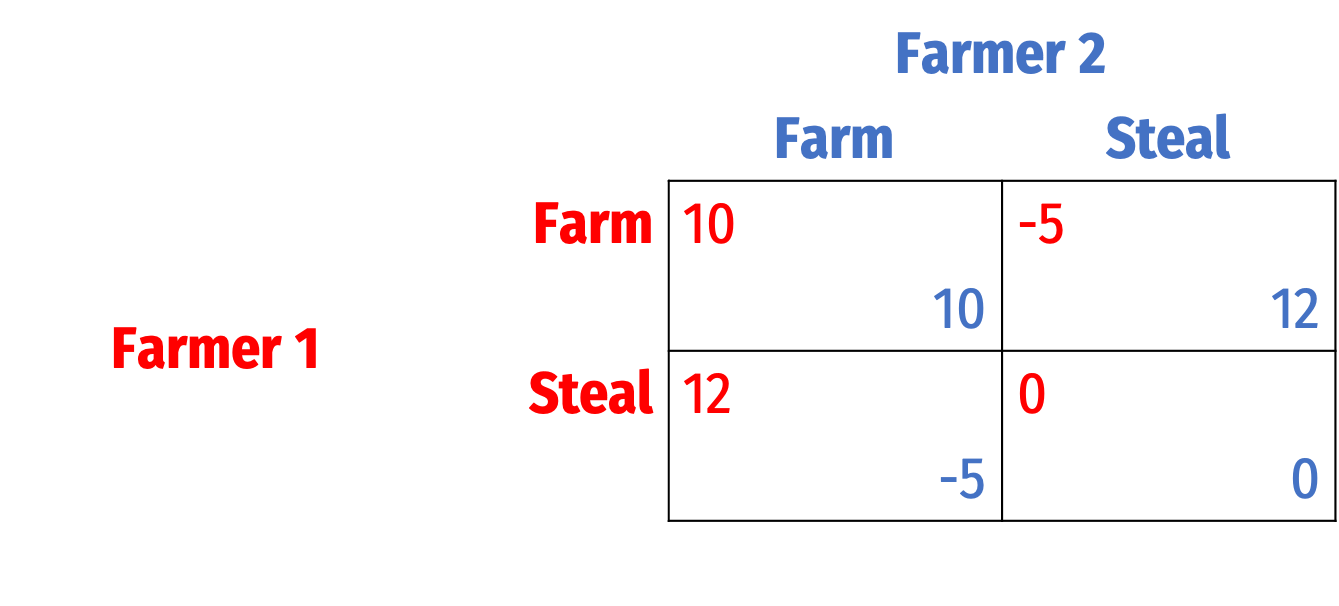

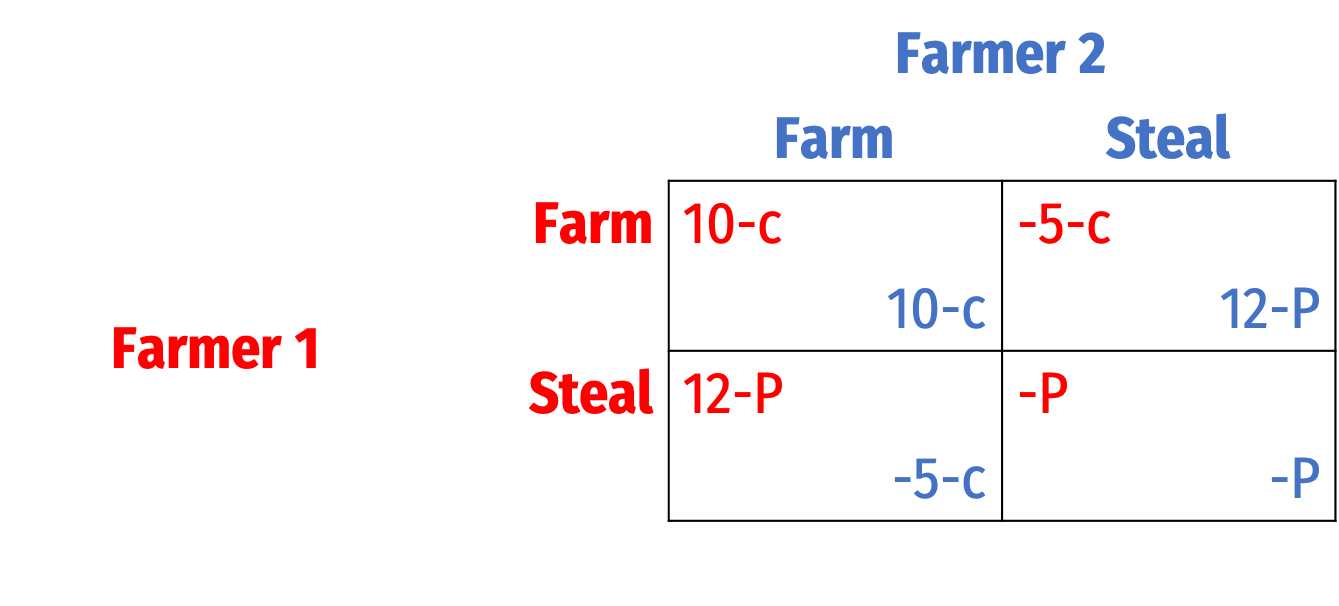

Recall the Game Between Farmers

Recall our original game that motivated the need for property rights

Farmers set up a property rights system

- Had costs \(c\) of administering

- Set punishment \(P\) for theft

If \(10-c>12-P\), then (Farm,Farm) becomes an equilibrium

Today we'll take a deeper look at \(c\)

Thank Property Rights for Thanksgiving!

The Pilgrims arriving at Plymouth Rock in 1620 immediately set up a collective property system

All farmland held in common, no private ownership

Promptly led to famine

Thank Property Rights for Thanksgiving!

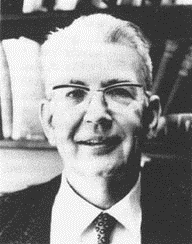

William Bradford

1590—1657

1st Governor of Plymouth Colony

“All this while no supply was heard of, neither knew they when they might expect any. So they began to think how they might raise as much corn as they could, and obtain a better crop than they had done, that they might not still thus languish in misery.”

“[A]fter much debate of things, the Governor...gave way that they should set corn every man for his own particular, and in that regard trust to themselves; in all other things to go on in the general way as before. And so assigned to every family a parcel of land, according to the proportion of their number, for that end...This had very good success, for it made all hands very industrious, so as much more corn was planted than otherwise would have been by any means the Governor or any other could use, and saved him a great deal of trouble, and gave far better content. The women now went willingly into the field, and took their little ones with them to set corn; which before would allege weakness and inability; whom to have compelled would have been thought great tyranny and oppression.”

Bradford, William, Of Plymoth Plantation 1620-1647

Thank Property Rights for Thanksgiving!

William Bradford

1590—1657

1st Governor of Plymouth Colony

“The experience that was had in this common course and condition, tried sundry years and that amongst godly and sober men, may well evince the vanity of that conceit of Plato's and other ancients applauded by some of later times; that the taking away of property and bringing in community into a commonwealth would make them happy and flourishing; as if they were wiser than God. For this community (so far as it was) was found to breed much confusion and discontent and retard much employment that would have been to their benefit and comfort. For the young men, that were most able and fit for labour and service, did repine that they should spend their time and strength to work for other men's wives and children without any recompense. The strong, or man of parts, had no more in division of victuals and clothes than he that was weak and not able to do a quarter the other could; this was thought injustice. The aged and graver men to be ranked and equalized in labours and victuals, clothes, etc., with the meaner and younger sort, thought it some indignity and disrespect unto them. And for men's wives to be commanded to do service for other men, as dressing their meat, washing their clothes, etc., they deemed it a kind of slavery, neither could many husbands well brook it. Upon the point all being to have alike, and all to do alike, they thought themselves in the like condition, and one as good as another; and so, if it did not cut off those relations that God hath set amongst men, yet it did at least much diminish and take off the mutual respects that should be preserved amongst them. And would have been worse if they had been men of another condition. Let none object this is men's corruption, and nothing to the course itself. I answer, seeing all men have this corruption in them, God in His wisdom saw another course fitter for them.”

Bradford, William, Of Plymoth Plantation 1620-1647

Property Rights Internalize Externalities

Harold Demsetz

1930-2019

“A primary function of property rights is that of guiding incentives to achieve a greater internalization of externalities. Every cost and benefit associated with social interdependencies is a potential externality. One condition is necessary to make costs and benefits [become] externalities. The cost of a transaction in the rights between the parties (internalization) must exceed the gains from internalization. In general, transacting cost can be large relative to gains because of ‘natural’ difficulties in trading or they can be large because of legal reasons,” (p.348).

“Property rights develop to internalize externalities when the gains from internalization become larger than the costs of externalization,” (p.350).

Demsetz, Harold, 1967, "Towards a Theory of Property Rights," American Economic Review 57(2): 347-359

But Property Rights Are Costly

Many decisions impose an externality on other parties

Externalities can be solved by defining property rights and permitting exchanges

There are always transaction costs to exchange

If transaction costs are low, efficient to create & exchange property rights

If transaction costs are high, inefficient to create property rights!

It's Just a Cost-Benefit Calculation

Essentially, does MB > MC of internalizing the externality?

- If yes: create property rights, internalize externalities

- If no: leave as commons, incur externalities

Exogenous shocks — opening new markets, new technologies, etc — can change this equilibrium!

Efficient to Keep as a Commons

Harold Demsetz

1930-2019

“A close relationship existed, both historically and geographically, between the development of private rights in land and the development of the commercial fur trade.

“Because of the lack of control over hunting by others, it is in no person’s interest to invest in increasing or maintaining the stock of game. Overly intensive hunting takes place.

“Before the fur trade became established, hunting was carried on primarily for purposes of food and the relatively few furs that were required for the hunter’s family. The externality was clearly present...but these external effects were of such small significance that it did not pay for anyone to take them into account.” (p.351).

Demsetz, Harold, 1967, "Towards a Theory of Property Rights," American Economic Review 57(2): 347-359

...Until an Exogenous Change

...Until an Exogenous Change

Harold Demsetz

1930-2019

“[T]he advent of the fur trade had two immediate consequences. First, the value of furs to the Indians was increased considerably. Second, and as a result, the scale of hunting activity rose sharply. Both consequences must have increased considerably the importance of the externalities associated with free hunting. The property right system began to change.”

“[Algonkians and Iroquois] divide themselves into several bands in order to hunt more efficiently. It was their custom...to appropriate pieces of land about two leagues square for each group to hunt exclusively. Ownership of beaver houses, however, had already become established, and when discovered, they were marked. A starving Indian could kill and eat another's beaver if he left the fur and the tail.”

“The principle of the Indians is to mark off the hunting ground selected by them Dy blazing the trees with their crests so that they may never encroach on each other...By the middle of the century these allotted territories were relatively stabilized,” (p.352).

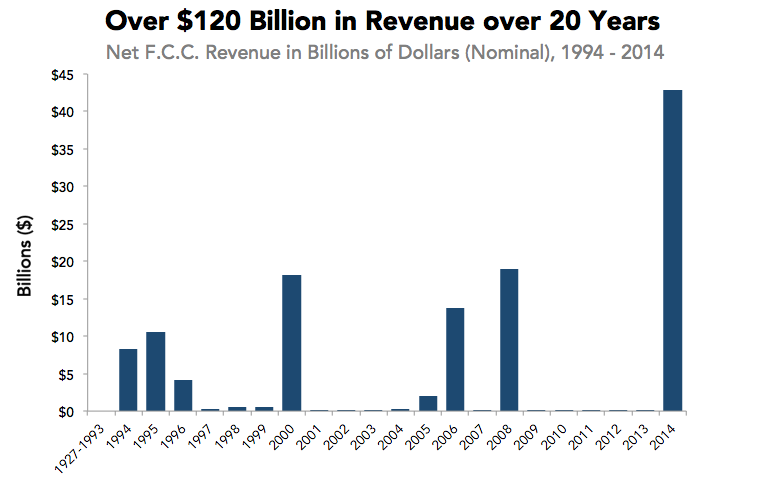

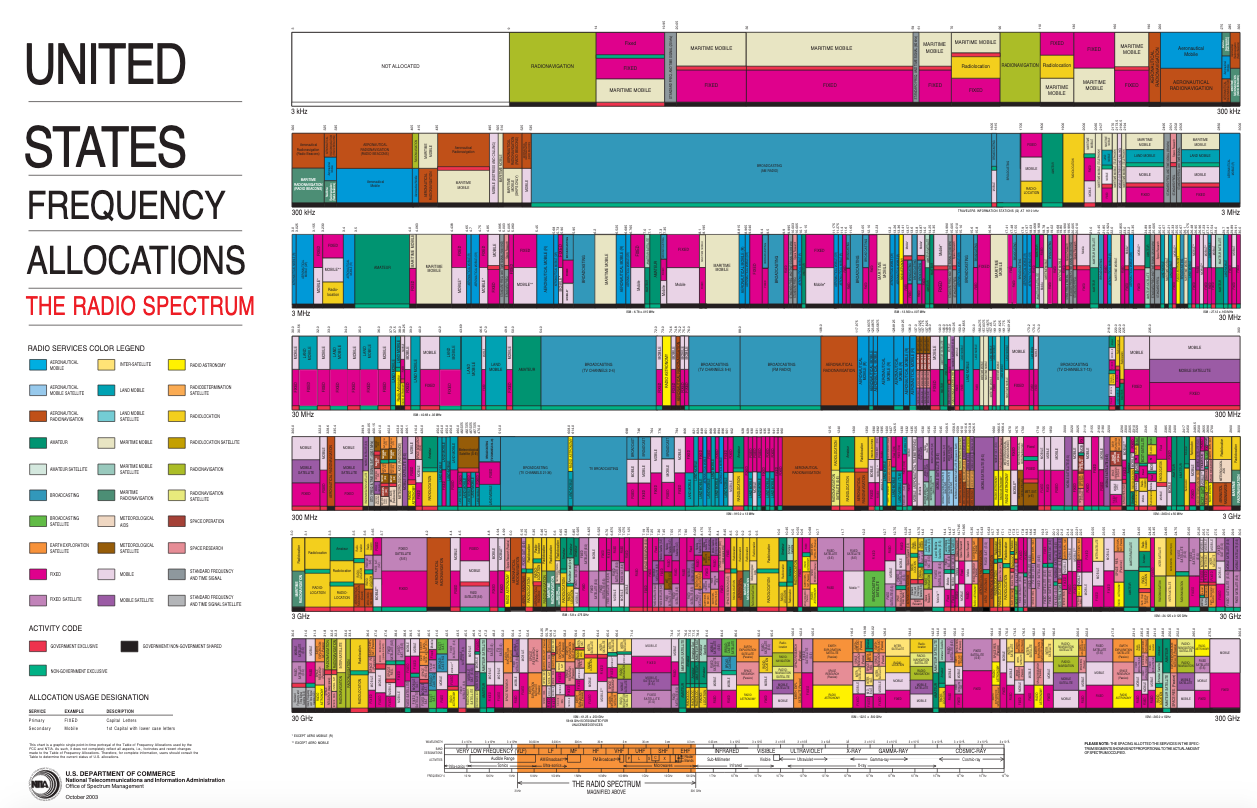

Technology Can Raise the Benefits of Property Rights

The electromagnetic spectrum allocated by the Federal Communications Commission to private parties (high res)

Summarizing Coase & Demsetz

Coase: if property rights are clearly defined and tradeable, we'll get efficient outcomes

- Fix externalities by expanding property rights

Demsetz: yes, but this comes at a cost!

- Property rights will expand only when the benefits outweigh the costs

- Either because benefits rise, or costs fall

Of Course, Coase Knew About Transaction Costs!

Ronald H. Coase

(1910-2013)

Economics Nobel 1991

“If market transactions were costless, all that matters (questions of equity apart) is that the rights of the various parties should be well-defined and the results of legal actions easy to forecast.

“But...the situation is quite different when market transactions are so costly as to make it difficult to change the arrangement of rights established by the law.”

“In such cases, the courts directly influence economic activity.”

“Even when it is possible to change the legal delimitation of rights through market transactions, it is obviously desirable to reduce the need for such transactions and thus reduce the employment of resources in carrying them out.”

Coase, Ronald H, 1960, “The Problem of Social Cost” Journal of Law and Economics 3: 1-44

Transaction Costs & Some Normative Prescriptions

Transaction Costs

- Transaction costs: the costs of voluntary exchange (or markets)

- Search costs: cost of finding trading partners

- Bargaining costs: cost of reaching an agreement

- Enforcement costs: trust between parties, cost of upholding agreement, dealing with unforeseen contingencies, punishing defection, using police and courts

Focus on Bargaining Costs

- Now that we have discussed bargaining, consider some types of associated transaction costs

1) Asymmetric information

- Lemons problem (Akerlof 1970)†

- Adverse selection & moral hazard

† I cover this in detail in this game theory lecture.

Focus on Bargaining Costs

- Now that we have discussed bargaining, consider some types of associated transaction costs

2) Private information

- not knowing each other's BATNAs

- bargaining requires revealing private information

- parties reluctant to divulge information

Focus on Bargaining Costs

- Now that we have discussed bargaining, consider some types of associated transaction costs

3) Large number of parties

- free riding, public goods problem, hold out problem

Focus on Bargaining Costs

- Now that we have discussed bargaining, consider some types of associated transaction costs

4) Uncertainty about property rights, BATNAs, the value of the property, etc

Focus on Bargaining Costs

- Now that we have discussed bargaining, consider some types of associated transaction costs

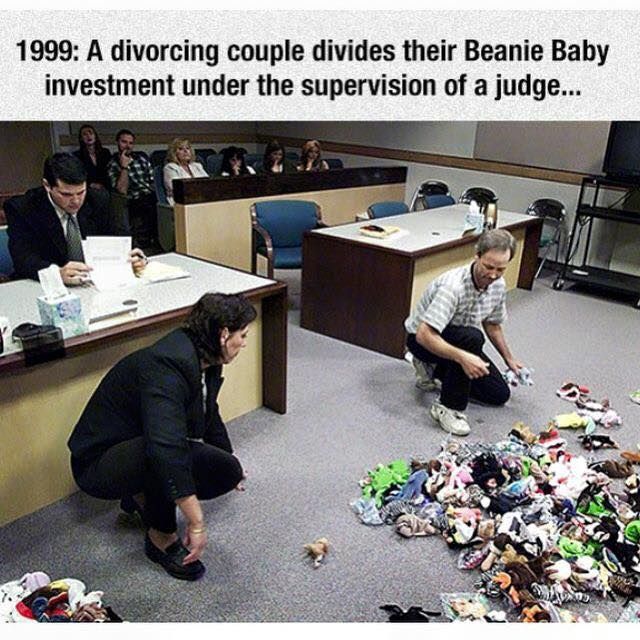

5) Enmity between parties

- emotions cloud rationality

- can you negotiate with someone you consider a mortal enemy?

- after trial, some parties refuse to bargain!

![]()

Focus on Bargaining Costs

- Now that we have discussed bargaining, consider some types of associated transaction costs

5) Enmity between parties

- emotions cloud rationality

- can you negotiate with someone you consider a mortal enemy?

- after trial, some parties refuse to bargain!

Transaction Costs and the Law

When transaction costs are low

- bargaining is easy

- initial allocation of property rights doesn't matter, can trade until reach efficient outcome

When transaction costs are high

- bargaining is hard

- initial allocate of property rights does matter, since trade may not occur (or is costly)

Two Normative Approaches to Law & Economics

Design the law to:

1) Minimize the cost of bargaining

- Normative Coase: “Structure the law so as to remove the impediments to private bargaining”

Two Normative Approaches to Law & Economics

Design the law to:

1) Minimize the cost of bargaining

- Normative Coase: “Structure the law so as to remove the impediments to private bargaining”

2) Minimize the need for bargaining

- Normative Hobbes: “Structure the law so as to minimize the harm caused by failures in private agreements”

Two Normative Approaches to Law & Economics

- Compare the costs of each approach

- Normative Coase: cost of bargaining, lubricate private exchange

- Normative Hobbes: information costs of determining how to efficiently allocate property rights

Two Normative Approaches to Law & Economics

- Compare the costs of each approach

- Normative Coase: cost of bargaining, lubricate private exchange

- Normative Hobbes: information costs of determining how to efficiently allocate property rights

- When transaction costs are low and information costs are high, structure the law so as to minimize transaction costs

Two Normative Approaches to Law & Economics

- Compare the costs of each approach

- Normative Coase: cost of bargaining, lubricate private exchange

- Normative Hobbes: information costs of determining how to efficiently allocate property rights

When transaction costs are low and information costs are high, structure the law so as to minimize transaction costs

When transaction costs are high and information costs are low, structure the law so as to allocate property rights to whomever values them the most